Legend has it that, thousands of years ago, King Nebuchadnezzar II wanted to offer his wife Amitis a gift. He created a city filled with gardens where plants and trees grew everywhere so that she would not miss the mountains of her homeland. Today, we know them as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

This is just one of the many unconfirmed theories that attempt to reconstruct the history of the ancient city of Babylon. What we do know is that the living walls were a common part of architectural designs from different parts of the world in ancient times. They helped reduce the temperature inside buildings, contribute to biodiversity, and increase beauty in the streets, just like they do today.

Nowadays, vertical gardens and green roofs are being presented as a solution to harness the benefits of nature in cities, improve their habitability, and contribute to adapting to climate change. Though they may seem like novel solutions, the truth is that engineers and architects can look to history to learn about using these walls of green.

The hanging gardens of antiquity

It is believed that construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon began around the 6th century BC on the banks of the Euphrates River. There are no archaeological remains, but ancient texts describe them as an orchard of plants and trees like palm trees that hung from the terraces and covered ceilings and walls. The water for irrigation came from the river through channels and also flowed in fountains that kept the gardens cool.

Representation of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Fantasy Art (Flickr)

There is some consensus on the idea that plants for ornamental purposes (not only food production) emerged in the historical region of the Fertile Crescent. There, in the territories lying between the source of the Nile and what is now western Iran, families began to cultivate their own private gardens. These were not limited to flowers and plants; they often also combined architectural pieces, sculptures, and fountains.

Later on, in the Mediterranean region, Greeks and Romans began to use vines and other plant species differently. In addition to being cultivated to produce fruits, they were planted for aesthetic purposes and to give shade in places where it’s not possible to grow trees. This custom is upheld to this day.

From the United Kingdom to Spain

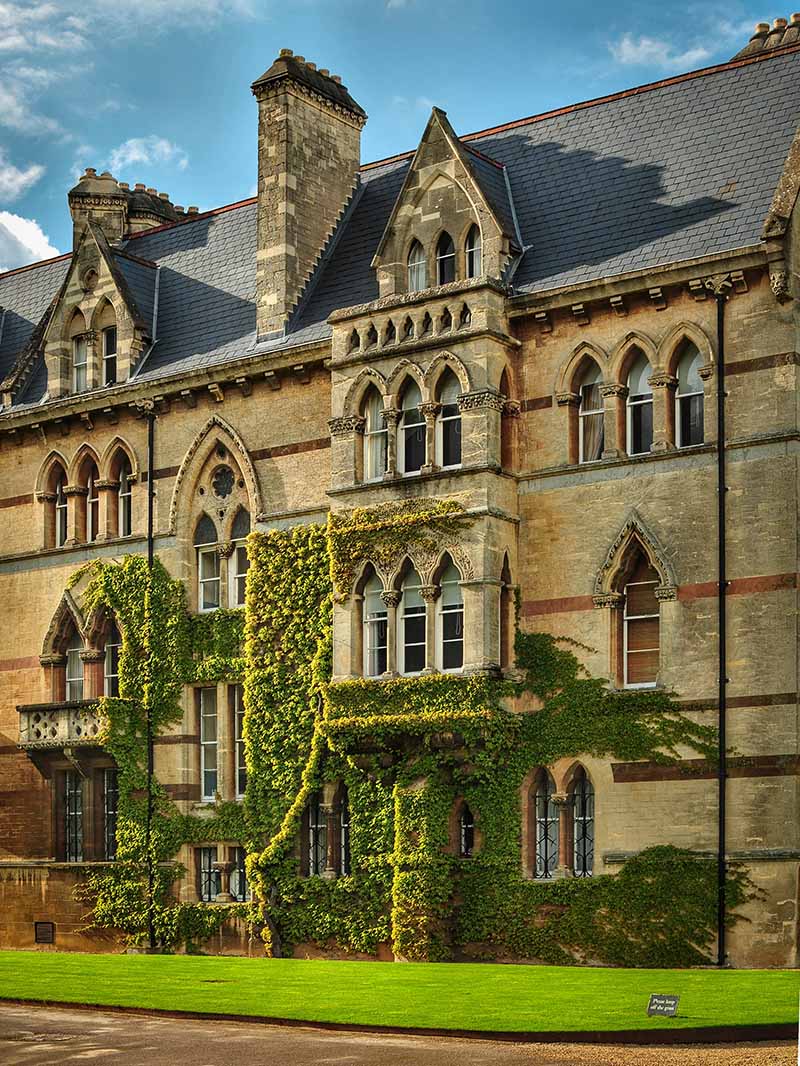

Throughout history, it has been commonplace for homes in humid climates to have vegetation on their walls. In the United Kingdom, for instance, ivy and roses have been considered a symbol of distinction in mansions and grand Victorian houses. Live hedges are also considered cultural heritage in the UK, and they play an important role in preserving biodiversity and preventing soil erosion.

Victorian house with ivy on its walls. Victor Forgaks (Unsplash)

The tradition of keeping vegetation on the walls can also be found in some regions of northern Spain, such as Galicia and Asturias. Further south, where high temperatures require solutions for keeping homes cool, social life in the houses has revolved around a central courtyard. In Andalusia, it is common for these patios to have fountains and walls full of plants that help lower temperatures on the hottest days.

Solutions for 21st-century cities

In recent centuries, urban development has led numerous cities around the world to grow into huge chunks of cement and concrete where there is hardly any vegetation.

In 1938, the American architect and professor Stanley Hart White patented a solution to create vertical gardens, which he named botanical bricks. Almost half a century later in the 1980s, French botanist Patrick Blanc popularized the idea of vertical gardens. In 1988, he installed the first plant wall in the City of Sciences and Industry in Paris, and since then, his green walls have been incorporated into various cities around Europe.

In recent decades, the concept is becoming more and more common. Its benefits go beyond those from centuries ago: today, they help clean the air of pollutants, thus reducing mortality levels; they reduce the urban heat island effect and also limit buildings’ energy consumption, to name just a few effects.

They also improve the health and well-being of citizens who, in many cases, have forgotten the benefits of living in proximity to nature. Some good examples are the Vertical ForestING project by architect Steffano Boeri, a new generation of buildings that include nature in their design. The first was built in Milan in 2000 and has more than 15,000 plants and hundreds of trees and shrubs.

Image of the Vertical Forest in Milan. Zac Wolff (Unsplash)

Other examples of living walls that have made their way around the world are the Singapore Bay Gardens, those that cover the facade of the Sor Juana Cloister University in Mexico City, and those that adorn the Gaia B3 hotel in Bogotá.

Main image: Representation of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon. Study of Archepoetics and Prospective Visualistics (Flickr)

There are no comments yet