How the Roman aqueducts were built and where the most famous ones that can still be visited are

30 of November of 2022

The Roman aqueducts played a vital role for the civilization of their time: providing an adequate water supply to hundreds of Mediterranean cities. It was a way of transporting drinking water through canals, ditches, tunnels, and overhead bridges.

As he masterfully explains, Isaac Moreno Gallo, a well-known technical engineer for public works as well as a historian, professor, and great educator – both on social media and in documentaries produced for Spanish Television – the Romans used water extensively: bathing daily in the thermal baths, drinking from public fountains, enjoying it in the homes that could afford to redirect the flow, and what was left over went to the public sewer.

HOW WERE THE AQUEDUCTS BUILT?

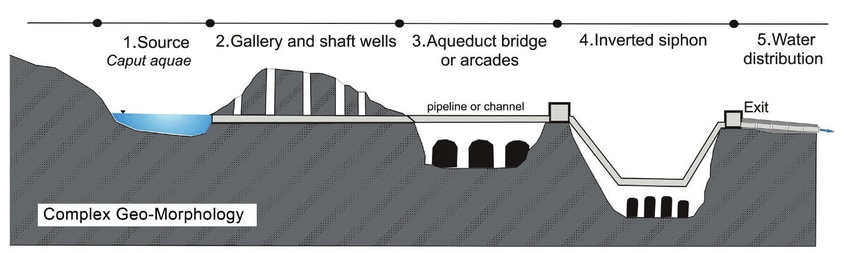

Diagram of a Roman aqueduct Pietro Todaro, Università degli Studi di Palermo

The Roman aqueducts required prior study so that the best water could be transported from springs to cities. This was because they only used the force of gravity to move water.

A topological study made it possible to compare the dimensions; the slope of the aqueduct was known to need to be at least 20 centimeters per kilometer (the aqueduct descends 20 cm for every kilometer traveled). This meant a gigantic aqueduct spanning 50 km would require a drop of about 10 meters in altitude from the origin to the destination.

These engineering calculations and others related to pressure, pipes, and records of the tunnels may seem complex to calculate, but the Romans knew them well and applied “empirical science:” building to scale, enlarging models, seeing what worked in practice and what didn’t.This way, they decided where new cities should be built before they were founded, as dependence on water for daily life was a top priority. So much so that the largest cities would have two different aqueducts in case one failed or when repairs were needed.

The work involved digging the ditches and tunnels necessary so that the water could flow. Its leveling and slope had to be perfectly calculated before using bricks, stone, concrete, cement, and stone or lead pipes where needed. On some insurmountable slopes, they even built siphons, where the water went down and then up under higher pressure.

It was also customary to build bridges with channels at the top to cross valleys and gorges and thus avoid snaking across mountainsides in endless curves and over greater distances that would make the work impractical. Though most of the aqueducts go underground, today, we typically call the parts built on bridges “aqueducts.”

WHICH ARE THE FAMOUS AQUEDUCTS THAT CAN BE VISITED TODAY?

Fontana de Trevi (CC) Sten Ritterfeld

Despite the passage of time, many of the Roman aqueducts still exist, even if just partially, and can be visited. Historians and engineers never cease to be amazed by their construction, and from time to time, some new discovery is made, usually underground or in tunnels.

Rome and Italy – In ancient Rome, 11 large aqueducts totaling 500 km in length were built; of them, about 60 km were over arcades; in Italy, there are about 15 known ones. Each one served an area of the city, and some can be visited. The so-called Aqua Marcia, measuring 91 km long and transporting almost 190,000 tons of water every day, is the longest; others like the Annius Novus or the Aqua Claudia stretched over more than 65 km and practically had the same flow.

Aqueduct Park, Rome (CC) Misviajesporahi

In the Aqueduct Park, 8 km from the center of Rome, you can visit several arcades. One of the most curious cases is that of Rome’s Aqua Virgo, which is still used today – with some modern modifications, to be sure – to provide water to the Trevi Fountain and the lions of the Piazza del Popolo‘s central fountain.

Spain – There are about 25 known Roman aqueducts in our country; the world-famous Aqueduct of Segovia is undoubtedly the best known, as well as one of the most spectacular. It is thought to be so splendid simply because, at the time it was built (2nd century), aqueducts were a form of publicly displaying cities’ wealth and power – as we know, this also happens today.

In any case, it perfectly fulfilled its main task: transporting water from the Fuenfría in the Sierra de Guadarrama to the city. As it passes through the center of Segovia, it crosses a section measuring 813 meters that’s supported by 167 arches, reaching 28 meters in height and a slope of 1% (one meter in height for every 100 meters traveled).

Aqueduct of “Devil’s Bridge”

Other well-known and visitable aqueducts are the Aqueduct of Les Ferreres or “Devil’s Bridge” in Tarragona, and the Aqueduct of the Miracles in Mérida (Badajoz) with 830 meters of arches and 25 m in height.

The Caños de Carmona aqueduct is an especially interesting case; they are the remains of a 17 km aqueduct that supplied Seville and which over time fell into disuse in the midst of city streets, including a few arches, pipes, and a reservoir. It is easy to find and even to see in Google Street View: Luis Montoto, 28, Seville.

France – The Roman Empire built four main aqueducts in what is now France; of these, the Gier Aqueduct is the best preserved, as well as the longest of all at 85 km. Given its length, there are still many remains to visit on its route to the city of Lyon.

Another wonder is the Pont du Gard, which spanned 275 meters at a height of 49 meters over the Gardon – quite an engineering feat for its time. The water flowed a total of 50 km over several bridges in an intricate route.

There is also the Fréjus Aqueduct measuring 40 km, in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur area. There are more precious aqueducts in France, but almost all of them come from the medieval period or later, far from the time of the Romans.

Pont du Gard (CC) Benh Lieu Song

England – In what is now England, there are still some vestiges of the Roman presence in the form of aqueducts. There are about five, as visitable as they are interesting – though they’re somewhat small compared to the Roman or Spanish structures.

There is the Durnovaria in Dorchester, with some remains and tunnels; Longovicium, a fort in what is now County Durham, consists of two small aqueducts about 100 meters long, which were used for mining.

Finally, in Wales, you can find the aqueduct at the Dolaucothi gold mines, where water was directed for mining. It was active between the first and third centuries AD. One fun fact is the resemblance that some of the mechanisms for elevating water bear to the one used at the Spanish Rio Tinto mines.

The centuries have worn away at all these great works of human engineering. Many of these structures have disappeared, while some have been lucky enough to receive maintenance, renovations, or restoration every few centuries, often because they were still useful and could continue to be used.

Thanks to this, you can visit them today, enjoying not only the beauty of their ancient architecture but also some incredible samples of human ingenuity in achieving the impossible – in this case, getting water to where it was most needed to make it an everyday, healthy, comfortable resource. This undoubtedly transformed the lives of the Romans and, by extension, the rest of European civilization.

Main image: Aqueduct of Segovia (CC) Marco de Hevia

There are no comments yet