When Englishman Tim Berners-Lee proposed creating what would later be called the World Wide Web in 1989, few really understood the magnitude of his idea. Today, invisible connections are constantly sending millions of pieces of data from one end of the world to the other.

The truth is, Berners-Lee and the rest of the CERN workers who made the internet possible were able to find inspiration for their project in nature itself. One example is mycelium, a fungi’s root-like structure that creates huge, complex structures underground.

Without mycelia, there would be no life as we know it. This vast network (known today as the Wood Wide Web) connects forests with nutrients and makes many functions that are fundamental for the health of the planet possible.

In the not-too-distant future, mycelia could also become the basis of construction: different projects are looking into how to create solid, durable, sustainable materials to use for building houses and other structures out of this part of fungi. This is what’s known as myco-architecture.

A lightweight, resistant material

The mass composed of mycelium has properties that are in high demand in the construction sector: it is organic, biodegradable, dense, strong, light, and resistant. It also works as an insulator and fire retardant, and it can filter water.

Yet another of its many advantages is that it can be produced practically anywhere, and for cheap: unlike plants, fungi (mushrooms, molds, and yeasts, for instance) don’t carry out photosynthesis; they nourish themselves with degrading organic matter. Therefore, they’re typically found in any ecosystem.

Example of how the mycelium connects different fungi into one body. Pradejoniensis (Wikimedia Commons)

Nowadays, various initiatives are using the mycelium from fungi to create blocks or bricks since it is easy to get it into different shapes– you simply need a mold it can grow in to make it expand and fill this space. Once this is done, the mass is baked to turn it into a hardened material.

Mycelium could also be used as a substitute for cement. Thanks to its adhesive properties, by letting it grow between two materials, it can unite them.

The projects for using mycelium on Earth…

Exterior of The Growing Pavilion. Eric Melander (Growing Pavilion).

In 2019, the Dutch Design Week inaugurated the Growing Pavilion, a 10-ton structure composed of five main materials: mycelium, wood, waste from agricultural activities, bulrush, and cotton.

The walls of this pavilion, which aims to raise awareness about the importance of building with sustainable materials, are composed of 88 panels where mycelium is mixed with other natural fibers. The combination forms a material that’s resistant, lightweight, fireproof, and water-repellent.

Inside the Growing Pavilion. Eric Melander (Growing Pavilion).

Another project, this time from Utrecht University, goes a step further and is committed to creating bricks with living organisms that can keep growing and self-repair. “The building then in fact becomes a sensitive and adaptive system: when it is warm, it becomes porous, when it is cold, the material has an insulating effect. By not killing off the fungus, a possible hole can grow back and you have self-repairing material,” explains Han Wosten, professor of microbiology at the Dutch university.

…And in space

Living in new environments requires innovative architectural solutions. That’s why NASA’s Ames Research Center is studying what technologies can help us create structures from mycelia on the Moon and on Mars.

“Right now, traditional habitat designs for Mars are like a turtle — carrying our homes with us on our backs – a reliable plan, but with huge energy costs,” says Lynn Rothschild, the lead researcher on this spatial myco-architecture project. “Instead, we can harness mycelia to grow these habitats ourselves when we get there.”

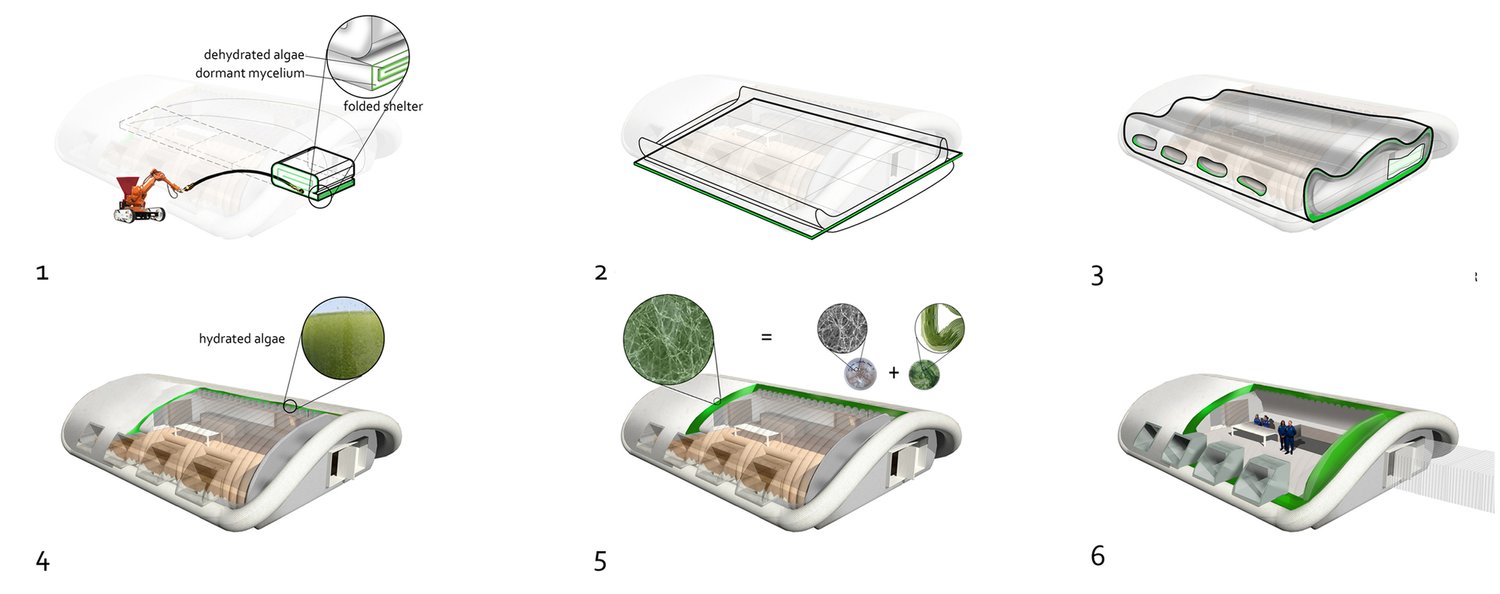

One of NASA’s plans is therefore growing the materials directly on the Moon or on Mars. The possibilities include bringing basic structures to which mushrooms can be added once they’re in place so that the mushrooms can grow around them and create habitats that support life.

Housing prototype for Mars. Red House Architecture.

“When we design for space, we’re free to experiment with new ideas and materials with much more freedom than we would on Earth,” Rothschild says. “And after these prototypes are designed for other worlds, we can bring them back to ours.”

This means that NASA’s experiments have a dual aim: to develop materials for space that can also help make more sustainable, less polluting construction on Earth.

Main image: Jesse Bauer (Unsplash)

There are no comments yet