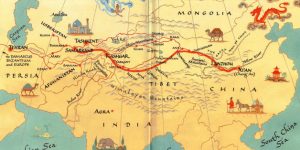

It took him three and a half years, along a winding route across the Mediterranean and what is today Turkey, to subsequently cross the Persian territories (current day Iran), Central Asia and finally reach China. Marco Polo, together with his father and his uncle, was one of the first Westerners to set foot in the Far East and write it all down in a book. Today, after centuries of neglect, the Silk Road is coming back to life, only with better connections.

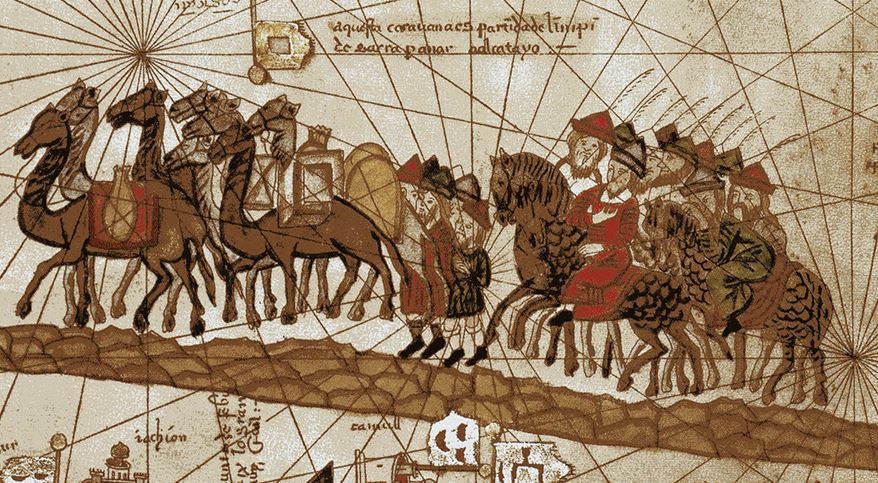

There is evidence of trade routes from China towards the west already some one thousand years B.C., but the Silk Road as such was only established some 2,000 years ago by emperor Wu of Han and his trusted diplomatic envoy, Zhang Qian. By the time Marco Polo travelled on it, in the 13th and 14th centuries of our era, it was already a complex network of roads and an important trade artery between East and West, for the exchange of goods such as jade, gunpowder, china and, obviously, silk, in addition to ideas, languages, cultures and news.

It took the Polo family three and a half years to complete their first adventure, according to estimates by National Geographic, given that there are no direct sources of information regarding those trips. Today, it takes the freight train 21 days to cover the distance of a little over 13,000 km between Madrid and Yiwu (China). The Silk Road is recovering its importance, with roads and rail becoming its greatest ally.

Reproduction of a map of the old Silk Road / Yale University

One Belt, One Road

The Silk Road of the 21st century may have changed its name, but it still retains its essence. The project once again originates in China and has two major aims: to drive investment in infrastructures (and many other sectors) and strengthen geopolitics and the trade relations of this Asian giant. The initiative, called One Belt, One Road (OBOR), is a large umbrella under which China has designed an ambitious investment programme in Eurasia.

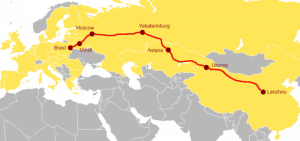

“The economic belt of the new Silk Road crosses China, Central Asia, Russia and Europe. It will connect China with the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean”, says consulting company DBS in a report on the megaproject. “It will concentrate on building new infrastructures crossing Eurasia and creating large economic corridors from China to Europe, the Middle East and South East Asia.”

According to figures from DBS, one of every three ongoing projects is associated with land transport, especially the construction of roads, highways and railway lines. In addition to the Asian giant, some 60 other countries (Including Spain, France and the UK) are involved in the initiative which will bring back Marco Polo’s dream, or rather, that of the emperor Wu of Han.

All aimed at gaining access to the Arabian Sea

Between China and the south of Pakistan (more specifically, the deep-water port of Gwadar), there are 62 projects under way. This is the CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor), the most developed commercial artery of the One Belt, One Road mega project. Investment to date totals 38 billion dollars, and it is estimated that this could reach 62 billion. A third part of this amount is being spent on five motorways which together represent 3,000 km of asphalt, and three railway lines connecting China with the Arabian Sea at Gwadar.

The other land corridors, implementation of which is rather slower, will connect China with Russia through Mongolia; with Turkey through all the Central Asian republics; with the Indochina peninsula; and with India. In total, 26 ongoing road, tunnel and bridge projects, according to the Hong Kong Trade Development Council (HKTDC). And, on the horizon, the most ambitious project of them all: a land connection with Europe.

“The sheer scale of OBOR is magnificent in all dimensions: the aim is to connect 68 countries of Asia, Europe and North Africa, which together represent 35% of world trade, a population of 4.4 billion people or 70% of the world total, 55% of global GDP, and 75% of world energy reserves,” according to the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies (IEEE).

The New Eurasian Land Bridge project / OBOR Europe

The rebirth of Marco Polo’s Sinkiang

After three and a half years on the Silk Road, it is believed that Marco Polo entered China through what is today the vast region of Sinkiang, a name which in a loose translation from Mandarin Chinese would mean new frontier. It was one of the key points on the old Silk Road, and one which will recover its glory in the new version.

Land connections between Russia and Europe will go through Sinkiang. “The link to the heart of Europe will be via the New Eurasian Land Bridge, on a 10,000 km route connecting China with Europe through Russia,” as explained in the IEEE report.

Three major rail links will connect Asia with the European transport network in Poland and Germany and extend to the UK and Spain. Two of these are already in operation; with one of them, the Madrid-Yiwu line, being the longest rail link in the world. The road network in Central Asia and Turkey will also be strengthened with the aim of building a new entry point into Europe.

Despite all of these ongoing projects, there is no clear roadmap nor specific timeframes for building these infrastructures. And no one knows for sure how or when they will be finished. It’s all part of a dream of asphalt, iron and steel which serves to remind us of the value of roads and communications to make the world just that little bit smaller. A dream that will enable the Marco Polos and jade traders of the 21st century to take a little bit less than three years to cross Eurasia.

There are no comments yet