From the Yukon to Tierra del Fuego: 48,000 kilometers of asphalt and an insurmountable obstacle

20 of November of 2018

In English, it has earned the title of highway, even if it is sometimes more like a main road. It is neither a unique road, nor is it completely asphalted. It is not even finished. Even so, it has been the dream of bikers and road trip enthusiasts for almost a century. This is the Pan-American Highway, a 48,000-kilometer route from north to south across the globe. A road to end all roads, unfinished because of one single, insurmountable obstacle.

The Pan-American Highway holds the Guinness Record for being the longest road in the world that can be traveled by car. At least in theory, in connects two mythical sites: the Yukon in the northwest corner of Canada, and Tierra del Fuego in Argentina. The history of this highway that is not a highway tells us about large-scale works, their difficulties, and the importance of ground communication routes for countries. And it also has a drop of adventure. Let’s start at the beginning.

One road to unite them all

“On July 1, 1936, the diplomatic meeting between Mexico and the United States at the International Bridge in Laredo, Texas, and Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, inaugurated the first section of what was later called the Pan-American Highway. The opening ceremony officially opened vehicular traffic from the Rio Grande to the Mexican capital,” explains researcher Víctor Manuel Gruel Sández, from the Autonomous University of Baja California.

The Pan-American Highway at its pass through Peru in the ‘40s

This brought ten years of construction on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border to an end. Thirteen years had passed since the project had been proposed at the Fifth International Conference of American States, held in Santiago, Chile, on March 25, 1923. Most countries showed enthusiasm, and by the sixth conference (1928), the idea of connecting North and South America by highway got the green light.

For Gruel Sández, the motivation behind this infrastructure was due to the Pan-American policy that sought to connect North and South America. Basically, early projects were focused on building a highway from the northern border of Mexico to Buenos Aires.

“In this context, and with the purpose of integrating roadways, the United States offered economic support to Latin American countries for financing their own transport networks,” the researcher indicates. However, not everyone accepted.

The project got underway, but problems were still to come. Lack of real investment, lack of commitment, and the region’s complicated geography hindered development in following decades. The section that gained the most momentum is also the best-known stretch today: the Inter-American Highway between Nuevo Laredo (Mexico) and Yaviza (Panama).

With the exception of the Mexican section, the rest of this project was financed with the help of the United States. Although its inauguration was announced in 1946, construction on the Inter-American Highway was completed in the late 1960s, though not completely asphalted. And to the south of Yaviza? Nothing. The road had hit a wall that remains unsurmountable to this day.

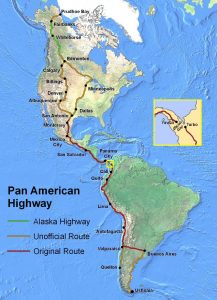

Map of the Pan-American Highway / Seaweege

The Darién Gap

Geography is capricious. Sometimes, it turns a place into a crossroads of histories and civilizations. The Arabian Peninsula or modern-day Turkey are some of those enclaves that, because of their position on the map, have been imperative stops on many routes. Other times, however, what was meant to be a crossroads becomes an impasse. This is the case for Darién, a swath of dense jungles and swamps between the Isthmus of Panama and Colombia, just south of Yaviza. A historic barrier between the northern and southern parts of the American continent.

The so-called Darien gap actually occupies part of the Panamanian province of Darién and the regions of Antioquia and Chocó in Colombia. It is an area with great biodiversity that also hides some of the best beaches in the Caribbean. It is also a place that has trapped hundreds of explorers and adventurers since Spanish conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa “discovered” it for Europeans. But that is another story.

The Darien jungle is the reason for the 130-kilometer gap that has no roads. The Pan-American Route continues to the south, from the Colombian town of Turbo to Ushuaia (in the Argentine province of Tierra del Fuego), Antarctica, and the South Atlantic Islands. Opinion is divided between Colombia and Panama. Should the jungle be protected and the natural border be respected? Or should one last effort be made to complete the longest road on the planet?

Aerial view of the Darién Gap in the region of Chocó, Colombia | Source: Flickr | Author: Andres Cuervo

Construction continues

With its highs and lows, enthusiasm for building the road through Darién has always been greater in Colombia (former president Álvaro Uribe was one of its greatest defenders). Arguments in favor of it are that the ground connection would contribute to the cultural and economic integration of the two neighboring countries, and it would help development in the northern part of the South American country.

As for naysayers, the stakes are primarily environmental. And not in vain, since the Darién is a biosphere reserve and a World Heritage Site. But in Panama, it has also been said that this road would help reinforce crime and drug trafficking on both sides of the border.

With the question open for debate, Colombia has two projects underway to improve connections to the doors of Darién throughout the rest of the country: the Americas Crossing and the Mountain Motorways. The ongoing construction of the Toyo Tunnel is part of the latter, which actually loosely groups various construction projects.

At 9.84 kilometers, it will be the longest in the country when it is opened around 2024. At the moment, it will help bring more traffic to Turbo. Who knows? Perhaps one day, taking this route will be synonymous with reaching Panama by road.

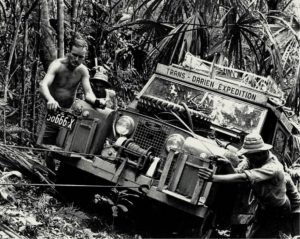

Expedition through the Darién in 1978 | Land Rover UK

So, is it possible to finish the Pan-American?

Yes, and it has already been done. There are two ways of doing it: crossing the hermetic Darién jungle, or going around it by sea or air. At different times, there has been a ferry between Panama and Colombia. Today, those who dare to take on the Pan-American’s 48,000 kilometers usually send their vehicle on a freighter and cross the border by plane.

Among those who have crossed the Darién by car, the first recorded expedition was made by Panamanians Amado Araúz and Reina Torres in 1960. It took the husband and wife team 136 days to cross the jungle. They traveled around 500 kilometers at an average pace of 200 meters per hour. All that to cross a stretch of land that measures no more than 87 kilometers, as the crow flies.

After them, another four expeditions successfully completed the journey. None of these trips would fall into the idyllic image of a summer road trip. Currently, the Darién continues to block the dream of the great Pan-American Highway. For now, the jungle will continue to defend itself with thick vegetation, swamps, mosquitoes, and dangerous ravines against the arrival of asphalt.

There are no comments yet