The Overland Trails, or How Cowboys and Caravans Blazed the Trails for Large Highways

10 of January of 2019

Today, half the world is led by the United States’ west coast. With companies such Facebook, Google, and Apple it seems impossible that, just two centuries ago, only vague stories of adventurers and fortune-seekers came out of that corner of the world. Back then, their steps into the unknown followed Native American trails. But today, those early paths are covered by some of the largest stretches of North American infrastructure. Gold fever, fur traders, caravans, and cowboys populate this history of epic highways.

At the start of the 19th century, the Western border, whose center was still located in Europe, was in the Appalachian Mountains. Almost no one was interested in what lay beyond that. Only a handful of explorers had crossed the Great Plains and the mountain ranges that the Native Americans had inhabited for millennia. But all that was about to change. The United States has just been founded as a nation. And its history is one of expansion.

“The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, and such principal stream of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado and/or other river may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce.” The words of Thomas Jefferson himself, founder and third president of the United States, to explorer Meriwether Lewis in 1803, according to the publication The Oregon Trail.

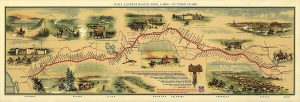

1860 map of the overland trail to California by William Henry Jackson. / US Library of Congress

His expedition served as the basis for early routes to Oregon and the Pacific. It was the origin of overland trails: those of Oregon, California, the Mormon Trail, and other lesser known and secondary trails. Even though these trails explored could only be travelled on foot or on horse for decades, Meriwether Lewis’s mission is often considered as the start of so-called Western Expansion.

The great North American migration

In search of new lands, spurred on by the California gold rush or in the search for religious freedom, there was a constant stream of travelers from east to west in the decades of 1840 and 1850. Explorers’ trails then gave way to wagon wheels. And all along those routes, stable communications for mail and commercial connections were established.

“This morning I started from my residence, near Napoleon, Ripley county, Indiana, for the Oregon Territory, on the Columbia River, west of the Rocky Mountains; though many of my friends tried to dissuade me from going.” So starts the diary of Methodist reverend Joseph Williams, written in 1841, one of the many testimonies collected in the detailed work of the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond.

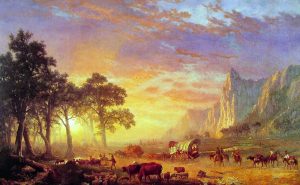

Painting by Albert Bierstadt, The Oregon Trail, 1869. / Boca Raton Museum

That same year, six months later, Williams settled in Willamette Valley, where the cities of Portland and Salem (so many kilometers from its homonym in Massachusetts, known for the witch trials) currently stand. Over the next two decades, almost half a million people would take this route, the Oregon Trail, establishing the earliest permanent settlements in the western United States.

Towards the end of 1850, the southern alternative towards California won out in importance. There was one reason: gold fever. All along this route, the Butterfield Overland Mail Company became the first regular communication service between the eastern and western parts of the country. Their caravans, which traversed the trail between Memphis, Saint Louis, and San Francisco, set out twice a week, and they traveled loaded with mail and passengers. They took some 25 days to complete the route.

However, their reign would be brief. In 1870, the last mail caravan arrived at Denver, Colorado, according to historian Monica Weimer. The Union Pacific Railroad, founded only eight years earlier to bring trains to the Pacific Coast, would take on the responsibility of mail service from that time on. The train would dominate the country’s communications until the first decades of the 20th century with the entrance of the automobile.

Publicity photo for the first GTEL locomotive for the Union Pacific in 1953. / Union Pacific Railroad

Surviving routes

Today, more than 4,660 kilometers of roadway separate New Jersey and San Francisco. Without counting stops, the trip can be made in some 45 hours of uninterrupted asphalt. This trajectory runs along Interstate 80, one of the first highways in the United States. In the Nevada stretch, I-80 follows the trail made by Native Americans, first along the Truckee and Humboldt Rivers, and then the overland trail towards California.

But this highway is not the only road that follows the routes indicated in the past. Interstate 84 between Utah and Oregon was largely built on US 30, which, in turn, followed the wagon wheels that traversed the Oregon Trail. The same is true for Interstate 76 between Nebraska and Colorado, or US 34 between Chicago and Colorado, built in part on these old routes.

This can seem like a lot. But in reality, not much time has passed from the first trails to the big infrastructure of today. In fact, as the Smithsonian explains, the remains of different overland trails are still visible in many places in the country. At some of the most travelled points, you can even see the tracks of wagon wheels.

Paths between mountains. Routes to transverse on foot or on horse. Trails for caravans or traced by train tracks. Paved roads and asphalt highways. In the end, history is always the same. Moving, discovering, communicating, connecting, and trading. It is the history of Homo sapiens and their roads.

There are no comments yet