The day a train enthusiast, a gas lamp, and a wounded man changed traffic forever

18 of February of 2019

On January 2, 1869, an explosion rocked the area around Westminster Palace in London. Britain’s Houses of Parliament had just been renovated, but that wasn’t the cause of the explosion. A gas leak from an odd contraption that stood at almost seven meters (22 feet) tall had caused the accident. Fortunately, only one person, a policeman, had been injured.

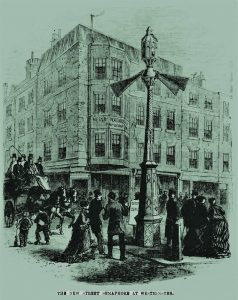

What exploded that cold January day was the first and, for a long while, only traffic light in history. It had been at the intersection of Bridge Street and Great George Street, one of the most heavily-trafficked areas in all of Victorian London, for a few weeks. It was installed on December 9, 1868, after being in development for almost three years. And almost four decades would pass until the invention would gain popularity, then on the other side of the Atlantic. But that’s another story.

Source: Unsplash | Author: @iniguez

The Knight, Saxby, and Farmer traffic light

“The 20-foot monstrosity rose up in the middle of the road […] two arms stretching up during the day, a gas lamp glowing like a gaping maw at night. Built by engineers, designed by a railway manager, and approved by Parliament, the strange contraption had a purpose as serious as its appearance was strange: to protect pedestrians from carriage traffic and keep the streets outside the House of Parliament from filling with congestion,” writes Lorraine Boissoneault in Smithsonian Magazine.

The first traffic light, as revealed in the Victoria County History archive, was designed by a train enthusiast. At the time, John Peake Knight was superintendent of traffic at the South Eastern Railway company. In those years when the first metro lines and commuter trains were being built, unsuccessful attempts were made to reduce traffic on city streets.

And what if we tried to regulate traffic like we do with trains? Knight’s idea may seem obvious, but back then it was difficult for him to convince a few politicians of the need to set stricter traffic regulations. “The traffic light became an innovative way to deal with managing the traffic of people, animals, and vehicles, based on Knight’s long experience with trains and by which flows could be regulated depending on their speed and direction,” reads the Victoria County History archive.

Following Knight’s ideas, Saxby and Farmer, two engineers who were experts in railway signals, built the contraption. It didn’t have the red, yellow, and green lights that we’re used to seeing nowadays. It had two arms, copying police officers, that could be down (go), parallel to the roadway (stop), or in a middle position (caution). At night, a red gas light meant stop, and green meant caution.

Illustration of the Westminster traffic light published in the Illustrated Times.

What would traffic have been like 150 years ago?

Today, London is one of the world’s largest metropolises and the most populated city in Europe. And it’s been that way for a while. In the 17th century, it already had half a million inhabitants. When the traffic light came to Westminster, there were more than four million (six, if you count the suburbs). In comparison, Madrid had around 300,000 inhabitants at the time.

The capital of the United Kingdom was a city designed in the Middle Ages that had grown along the Thames River, and it was undergoing a population explosion because of the Industrial Revolution. Rush hours for entering and leaving factories had become a reality. And pedestrians had to deal with increasingly dense traffic, including horses. According to the book London, a Social History, some 270,000 workers traversed the city streets every day in 1850, and 27,000 of them were coming from the outskirts by wheeled modes of transportation.

Traffic was the first thing that caught the attention of foreigners who set foot in London. Danger was palpable for pedestrians and drivers alike. In fact, in the middle of the 19th century, in London alone between three to four people died every week in accidents. The data, presented by historian Judith Flanders in her book, The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’ London, also discusses the growing congestion and increase in traffic jams.

“They designed plans to improve traffic management. And they did it again. And again,” says Flanders. Until the arrival of the traffic light, which, in its barely four weeks of existence, demonstrated that improving regulation was the way to go to bring order to London’s chaos.

Absence and automation

After Knight’s traffic light exploded, these contraptions disappeared for more than 40 years. They didn’t return to London until well into the 20th century. When traffic lights returned to the United Kingdom as an American invention, they were still operated manually by police officers, but by then they had the three colors that we know today. The first design with red, yellow, and green was installed in New York in 1918 and in London in 1926.

Electric traffic light in the streets of Stockholm in 1953.

After a quarter of the 20th century had passed, traffic lights had become more necessary than ever before. A new vehicle, powered by horses as well as steam, was taking over the streets. Traffic from delivery cars and trucks and the need to regulate it in all cities, beyond specific problem areas, meant that the automation of these signals would soon be a necessity.

The first automatic traffic lights were installed in Los Angeles in the 1920s. They were from Acme, and they more or less worked like Wile E. Coyote’s inventions to trap the Road Runner. In fact, the first automatic machines installed in London also swung through the air by some strange whim of fate (even though they were a different brand). Today, electrification has made it safer, though it’s robbed us of a little adventure (maybe).

There are no comments yet