Oyambre Beach, or the First Big Spanish Hub

The gladdest moment in human life is a departure into unknown lands.

Sir Richard Burton

01 of July of 2019

In human beings, the call of adventure finds a response inversely proportional to their prudence when faced with circumstances. For someone like me, who has become more bourgeois over the years and ended up abandoning my sense of adventure, the Livingstonian purpose of existence reaches its height when the family car sets out on the N-4 for Despeñaperros, headed to any beach bar on the Costa del Sol.

To the relief and glory of our civilization, there is another, very different human biotype capable of carving out more gracefully adventurous fates. The pioneers of aviation fit this profile through their merits, prodigies of mental imbalance that, in the early twentieth century, elevated human horizons to new heights by transgressing, at the expense of their own physical integrity, all gravitational laws, from the myth of Icarus to the Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia.

These were people like the Wright brothers, Juan de la Cierva, or Ferdinand Von Zeppelin. Like Manfred Von Richthofen – the Red Baron; Ramón Franco, who manned the Plus Ultra seaplane in 1926 from Palos de la Frontera to Buenos Aires; or American Charles Lindbergh, who, years before declaring himself a Nazi sympathizer, would complete the first solo intercontinental flight from one side of the Atlantic to the other aboard the Spirit of St. Louis.

On June 14, 2019, was the 90th anniversary of one of these extraordinary aerial feats. That would be the first flight over the North Atlantic that landed in Spain as it did on a day like today in 1929. The anecdotal part of this story is that the landing did not take place at a conventional airport: neither on the runways of Barajas (the Spanish capital’s current airfield would not open to air traffic until 1931), nor in Barcelona, nor in the cradle of Spanish aviation, the century-old airport of Cuatro Vientos. And it didn’t touch down at an airfield – it had to make an emergency landing on one of the most spectacular beaches along the Cantabrian coast because the airplane carried an unexpected additional load in the fuselage: the first stowaway in the history of aviation, American Arthur Schreiber.

The Story of the Yellow Bird (L’Oiseau Canari)

When Lindbergh managed to fly from New York to Paris in 33 hours and 32 minutes in May 1927, he took home the $25,000 ($374,000 today) that tycoon and philanthropist Raymond Orteig had decided to award to whoever managed to perform this aerial feat over the Atlantic.

The lack of economic incentives from then on did not discourage other adventurers, many of whom ended up at the bottom of the ocean for eternity. Shocked by the many hundreds of accidents that happened, Raymond Poincaré’s French government decided to ban the take-off of transoceanic flights from its territory, a very wise decision that would find no reciprocity in its US counterpart, which did allow flights in the opposite direction to continue.

And this is where the story’s protagonist comes into play: French millionaire Armand Lotti, an heir to a hotel empire (a Parisian hotel on the Rue de Castiglione that today belongs to the NH Hotels chain still bears his name) bent on becoming the first Frenchman to have his name go down in the distinguished history of transatlantic flights. He had been blinded in one eye by a hunting accident, which forced him to settle for going as a co-pilot (and even still illegally), Lotti hired Rene Lefevre as an aerial navigator and experienced pilot Jean Assolant to sit at the controls of a Bernard-Hubert 191GR, christened l’Oiseau Canari and commonly known as the Yellow Bird.

How to get around the French Government’s severe ban on flying from France to the United States? By taking advantage of the leniency of Herbert Hoover’s administration and flying from the United States to the runway at the Parisian airport of Le Bourget, as the French leader‘s prohibitionist zeal did not go so far as to outlaw landing on Gallic soil.

Delving into the work, Lotti, Assolant, and Lefevre first flew from France to England in secret over the English Channel, got out of the Yellow Bird on English soil and loaded it piece by piece aboard the SS Leviathan, bound for the United States.

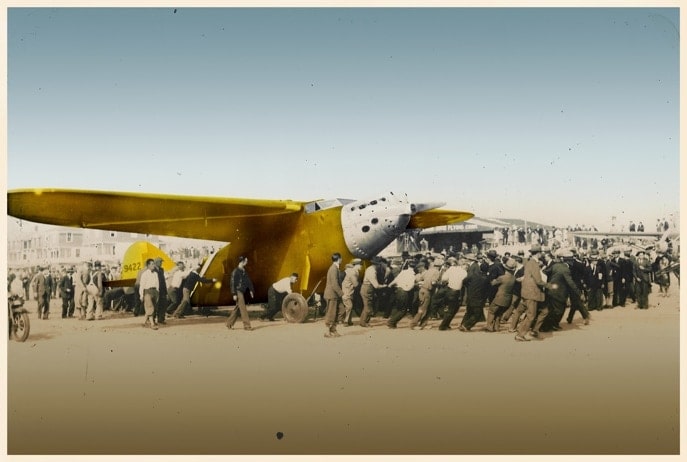

Once on American soil, and after an initial failed attempt, the big day arrived for the definitive takeoff on Old Orchard’s long beach in Maine. It was June 13, 1929, a clear day with perfect flying conditions. A wave of inquisitive folks and journalists showed up at the beach to witness the epic event, which was broadcast live by more than 100 radio stations from coast to coast in the United States.

The crew’s primary concern was Yellow Bird’s load. In the early days of aviation, weight was everything. The greater the load, the more fuel consumed. Naturally, last-minute nerves led Lotti and Assolant to unload 100 liters of fuel to lighten the weight of the aircraft by 90 kilos. With the food rationed properly, the only whim on board was Rufus, a little lizard 20 centimeters long given to them by local residents as a pet.

During the long takeoff ceremony, between the flashes of photographers’ cameras and the groups that formed around the fearless crew, no one realized that a man in his 20s, dressed in khaki pants and a bomber jacket borrowed from his brother, an aviator in World War I, snuck around the security perimeter around the plane and into a hatch at the back of the Yellow Bird. It was Arthur Schreiber, the first stowaway. But why did he climb aboard? Apparently, he’d made quite a gutsy bet with his friends the night before.

The take-off took place at 10:08h on Thursday, June 13. The maneuver was technically perfect, though it was later noted that the plane’s tail was slightly dragging through the sand. Perhaps these explanations were 20/20 in hindsight, but in any case, the Yellow Bird gained altitude until it disappeared into the horizon.

The first hour of the flight ticked by. Everything was going off without a hitch. Lotti, Assolant, and Lefevre were feeling quite content when, suddenly, the navigator noticed something touching his back. When he turned around, he was shocked to find a young man very respectfully introducing himself to them. At that very moment, still stunned, they knew that the weight of the four of them, along with poor Rufus, would keep them from getting to Paris safe and sound.

It was also too late to turn around and go back to Old Orchard. In an interview with the New York Times, Lotti later confessed that the crew’s first instinct was to throw the stowaway down the same hatch he’d snuck in by. After all, who would know? To Schreiber’s eternal relief, the discussion shifted to less homicidal options. In any case, there was undoubtedly a high-stakes question at hand. With the threat of a deadly leap still hanging over his head, the stowaway was persuasively convinced to sign a document stating that he would never try to take advantage of the fame that the flight would bring him if they escaped with their lives, a scenario that, when he agreed to it, was still a remote hypothesis.

Land the best you can

Source: cronicasdeloriente.com

The Yellow Bird started running out of fuel long before reaching the shores of the European continent. When they reached the Azores, Assolant decided to change course a few degrees further south to avoid the strong headwinds that were quickly emptying the plane’s tank. Fear beat in their hearts to the rhythm of the engine.

But the pilot’s expertise guided the airplane to the shores of northern Spain, a coastline that did not yet have very sophisticated navigation charts. They flew overhead looking for a place to land from a bird’s-eye view. Nothing seemed suitable until, suddenly, they spotted a beach wide and long enough to attempt a crash landing under half-hopeful conditions. It was Oyambre beach, a natural gem located halfway between the mountain villages of Comillas and San Vicente de la Barquera.

As Alfonso de Senillosa– one of the motors behind the recent restoration of the monolith commemorating that feat – recalls, after the first shout of joy for landing on the sand as the over-5,000-kilometer flight came to an end, the disoriented crew came down from the craft fearing that they had ended up in some remote corner of the planet, far from all civilization and especially from anywhere they could find the fuel they needed to continue the journey to Paris.

To their astonishment, the first human presence our protagonists came across was a distinguished group of members of high Spanish nobility who, late that afternoon, were refining their putting skills on the greens of Oyambre’s Royal Golf Club. This was Spain’s first golf course, which was opened in August 1924 by King Alfonso XIII and which, almost a century later, is still located in the same spot a few meters from the dunes of Oyambre beach, which was declared a natural park in 1988.

Once word spread about the odyssey, the Cantabrian beach made headlines around the world for several days. Correspondents from European, American, and national media flocked to the town of Comillas to cover the festivities that area authorities held for the crew, which had already forgiven their stowaway – who was very popular among local ladies – while waiting for the kerosene needed for the rest of the journey to arrive from Madrid.

Armand Lotti, Jean Assollant, René Lefévre y el polizón. Source: El País

That rough journey, which would fortunately reach its final destination, was a pioneer in many fields of aviation (the yellow bird is now on display at the Le Bourget air and space museum). It was the first nonstop flight to cross the Atlantic Ocean, it was the first one completed by a French crew, and it broke the record for speed (105 miles per hour) and distance. For the Spanish, it was the first flight in history between the United States and Spain. For those in Santander, it was the first flight that connected America with the Cantabrian continent.

There are no comments yet