Every once in a while, every self-respecting investor has a moment of doubt. How much value can my portfolio lose if things go wrong? As with everything in finance, there is an indicator, called Value at Risk. VaR tries to estimate what the expected maximum loss is for a time-set investment portfolio. In a real-time world, these intervals tend to be very short and don´t usually go more than a year out. But what if we wanted to run this analysis over a much longer term?

Recently, Schroders, the global fund manager, asked itself this question, and in answering it, the company came across a challenge. Financial modeling has its limitations. First, because the businesses of today are nothing like what they were a decade ago. Five of the ten most valuable companies in the world didn’t exist 20 years ago, and two more have been reinvented several times in that time (Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet -Google-, Berkshire Hathaway, Facebook, Alibaba, Tencent, Johnson & Johnson, and Exxon Mobil). Secondly, and more importantly, because the greatest source of uncertainty comes not so much from economic, financial variables but from extra-financial aspects, such as social, political or technological changes.

And if we’re looking to the future of our society and our markets, we have to ask ourselves a deeper question. Is our development model sustainable over time? Schroders’ conclusion is at least disquieting. If globally-listed companies internalized the costs associated with their environmental and social impacts, corporate profits would fall by 55% and one in three companies would suffer losses. Welcome to the age of sustainable finance.

A model for unsustainable development

The fact that our development model is unsustainable is not a motto or a political platform. It’s a proven reality. Right now, humanity consumes the equivalent of 1.7 planets, not to mention things like that, in the next ten years, the number of people who are middle class worldwide will triple, or that the world population will be around 10 billion people by 2050.

As for the future of work, that is uncertain. According to McKinsey, from now to 2030, 15% of jobs risk being automated not only in industry, but also in services. Wealth inequality, which was drastically lower for much of the 20th century, has been increasing for the past three decades in the West, fueling populism and polarization. But surely the biggest challenge facing humanity is climate change.

Global warming threatens to shift our benign, habitable planet to a hostile planet, to say the least. This process not only affects the climate (extreme weather events such as droughts, floods, almost yearly heat waves, and heavy storms). It also affects geopolitical stability (mass migrations; armed conflicts over access to basic resources such as water, food or soil), health (the spread of pandemics traditionally related to tropical climates), the agri-food chain (declining agricultural productivity), and, of course, the financial system.

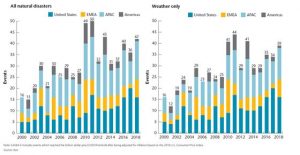

Some branches of the financial industry, such as the insurance sector, are beginning to feel the first shocks related to climate change. The frequency and severity of climate change-related claims have spiked considerably in recent years, and the average cost of climate-related claims has grown by 82%. This has piqued the interest of financial market regulators and supervisors, who have begun to develop regulations in order to improve transparency and climate risk management by asset issuers and particularly by key actors in the financial system (banks, insurers, managers, and asset owners). Ultimately, climate transition may entail a systemic crisis that requires the attention of supervisors.

The costs of climate change are starting to be evident

Big problems, big solutions.

Fortunately, the challenges for sustainability have been added to the global governance agenda, and this has resulted in the adoption of programmatic agendas. As such, the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda, with its 17 Sustainable Development Goals, have been important milestones in backing frameworks for countries regarding sustainability. At the climate level, the States are committed to making every possible effort to stabilize temperatures around 1.5 degrees Celsius and not exceed 2ºC above the pre-industrial era under any circumstances.

As for the 2030 agenda, it incorporates 169 specific aims that address issues such as access to water, clean energy, health, sustainable production and consumption, and combating poverty, among many more. However, these commitments, while fundamental, are not enough. For instance, current commitments to national emission reduction will still lead to temperature increases of more than three degrees, which is an assured climate catastrophe.

Faced with this dilemma, States have realized that they need two additional ingredients: incentives and regulation. On one hand, establishing a framework of incentives that entice the private sector to put its capacity for large-scale innovation and transformation to work for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is essential to transitioning from a reactive approach to a different, proactive one as for companies and investors.

If we consider it carefully, the Sustainable Development Goals are a great business opportunity for quite a few sectors, especially infrastructure construction. According to some studies, compliance with the SDGs could result in an increase of $1 trillion per year globally in infrastructure investment. Areas such as food and agriculture, cities, energy and materials, and health can benefit from this $12 trillion business opportunity.

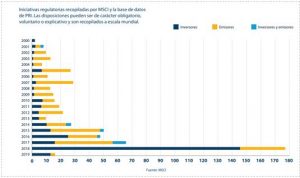

At the same time, developing a regulatory agenda aimed at strengthening governance of these aspects by companies and investors is becoming necessary. From this point of view, there has been a boom in regulations around transparency and management of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria in recent years. In 2018 alone, several jurisdictions implemented more than 170 regulatory initiatives regarding ESG criteria for both asset issuers and investors.

Evolution of regulation of ESG criteria worldwide

Within the European framework, the undisputed leader in this movement, the Sustainable Finance Plan stands out among several other policy initiatives. Its objective is to facilitate the allocation of private capital to financing sustainable projects. The cornerstone of this plan is the development of a sustainable finance taxonomy that can serve as a decision-making reference for different actors. Issuers and investors will find a common language that standardizes sustainable financial instruments (assets, investment products, and low carbon indices).

Agencies such as the European Fund for Strategic Investments find parameters for implementing their mandate to invest 40% of their assets in climate actions. Banking and stock market supervisory authorities can find criteria for developing climate stress tests or establishing requirements for green bond issuance brochures, for instance. Finally, the recently-announced European Green Deal from the new European Commission proposes, among other measures, the creation of a European Bank for Climate Investment, or the development of European climate law requiring the Union to be carbon neutral by 2050.

Sustainability and the value of money over time

Scholars say that financial markets anticipate the future and discount it in the present. Sustainability is no exception. To see this, let’s jot down some figures. At the beginning of 2018, assets managed under ESG criteria exceeded $31 trillion. There are now more than $90 trillion that conform to the United Nations’ Principles of Responsible Investment. So far this year, banking has facilitated more than $44 billion in loans associated with ESG variables, and more than $170 billion in green bonds has been issued globally.

“What is at the root of this sustainable finance boom?” the reader will ask. We found essentially two answers that are also compatible with each other. The most obvious one comes from altruistic motivation, which has to do with the ability to generate investment portfolios in line with the saver’s social and environmental values. This adds value to the owner of the assets, who invests their money by following their conscience, and it strengthens the reputation of the asset manager, avoiding uncomfortable situations when investors discover that they are financing products from companies that are “harmful” for society.

The altruistic answer is plausible, but it isn´t enough. After all, hordes of people haven’t been breaking down their banks’ doors clamoring for more sustainable investments yet. The second motivation is selfish and, perhaps, more powerful. It’s that the ESG criteria improve the financial performance of investments. If we look at the long-term performance of sustainability stock indices, we can see that all sustainability indices, with the exception of the United States, have surpassed their benchmarks both in terms of profitability and lower risk.

Sustainable Indices Tend to Improve Profitability Per Unit of Risk

This same pattern is also seen in bond portfolios where ESG performance is also tied to financial performance. For example, green bond indices have performed better than the generic index (Barclays Global Aggregate). Even in the most speculative sections – known as junk bonds – benefit from a lower default rate and higher recovery rates.

This brings us to what is frankly an interesting conclusion. Markets are already discounting a risk premium for sustainability. The difference in valuation between leading companies in sustainability, as compared to those lagging behind, is 9.9%.

What does this mean for Ferrovial?

The bottom line is that investors are responding positively to the rising value of sustainability not only worldwide, but also on the Spanish stock exchange. One study done by Forética found that leading Spanish companies in sustainability generated a higher return on the market at a rate of 4.7% per year over a period of 7 years. One of the main securities in the portfolio was Ferrovial, which, at a weight of 17%, accounted for 19% of the portfolio’s yield.

Investors Have Rewarded Sustainability on the Spanish Stock Exchange

In sum, sustainability creates value not only for the planet, but for companies as well. A good example of this is that environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria boost the appetite for investment and increase the value of assets. Let’s take this opportunity for sustainable finance.

There are no comments yet