A century ago, traffic in Madrid traveled on the left side of the road, whereas Barcelona’s was on the right. There were no state rules to regulate the direction of travel; and Spain’s capital wouldn’t be on the right of the road until 1924. But the subway never changed. A century ago today, the first line of Madrid’s Metropolitan Railway opened. From Sol to Cuatro Caminos, the subway cars were on the left. And that’s how it stayed.

The inauguration of Madrid’s Metro was delayed and came decades before the use of digital photo editing in print. That first construction on the Metropolitan would produce the team that eventually founded Agroman, today the construction division of Ferrovial. This company’s name would be forever linked to the history of Madrid’s Metro. But let’s go back to the beginning.

With eyes wide open

The first inauguration of the Madrid Metro took place on October 17, 1919. Construction had begun just over two years earlier, on July 17, 1917, by the Compañía del Metropolitano Alfonso XIII. That inauguration was strictly for the monarch and other authorities.

After traveling the 3.4 kilometers from Sol to Cuatro Caminos in about 10 minutes (the tram took half an hour aboveground), everyone took a photo for posterity. Back then, they had just one shot, and Alfonso XIII must have blinked. So they had to retouch it to make it look like his eyes were open.

¿Has visto esta foto? Alfonso XIII salió con los ojos cerrados en la inauguración y fue retocado después #metro95años pic.twitter.com/VT2wmCrLYq

— Metro de Madrid (@metro_madrid) October 16, 2014

The second inauguration took place several days later on October 31, 1919. On that day, 56,220 travelers got on the new subway. And thousands of curious onlookers wanted to witness this historical moment. They all had their eyes wide open to observe the future in route under the city streets. The chronicles of the day illustrate this occasion.

“Madrid will finally have that industrial thing that so decorates and properly dresses great modern cities. The stations have already been built at strategic locations, with their shining hardware at the service of this mechanical architecture,” remarked José María Salaverría in La Vanguardia, just days before the inauguration.

“The metropolitan will infuse Madrid with an air that it currently doesn’t have. In Madrid, as generally is the case across Spain, there are many slow things. It is exactly all those things about dynamism and hastiness that are against such slowness. Banks, joint-stock companies, underground roads,” he went on. “The metropolis will undoubtedly be the most revolutionary, life-giving, energetic thing that has been created in Madrid for many years.”

So on the day of the second inauguration for the masses, Madrid sprang forth “like a little boy with a new toy,” explained the chronicler for ABC. “The event caught the attention of curious, impatient individuals who formed a line next to the stations at Puerta del Sol and Cuatro Caminos. Meanwhile, down in the depths of the city, four trains were running […] Madrid is looking to Europe, standing tall with the other major capitals, being delighted in itself, and that’s it, a round of applause and a victory lap for the Otamendis!”

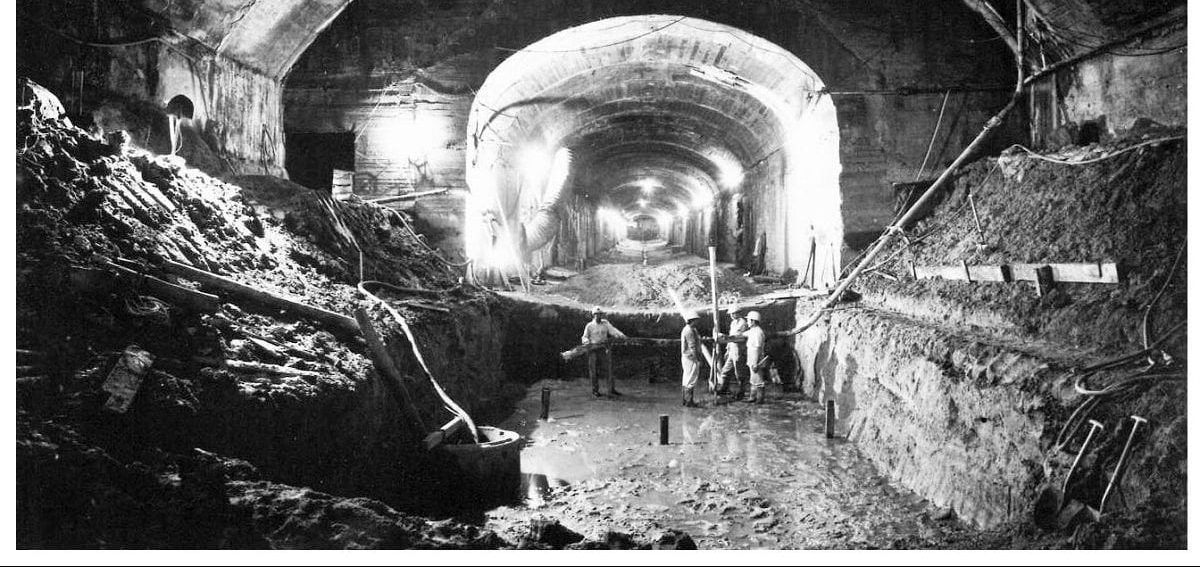

Tunnels for line 3 between Sol and Argüelles, a stretch originally built by Agroman. / Ferrovial Agroman

New lines and the origins of Agroman

The Otamendis were none other than engineers Miguel Otamendi, Carlos Mendoza, and Antonio González Echarte, the fathers of the first project for the Madrid Metro: four lines, 35 stations, and 154 miles of subway tracks. To get to where it is today (294 kilometers, 302 stations, and more than two million trips each day), construction started quickly.

In 1921, the Sol-Atocha line was opened, and in 1923, it was extended to Puente de Vallecas. While line 1 (sometimes known as the North-South line) was being expanded, construction on line 2 was moving forward at a good pace. In 1924, Sol was linked to the Las Ventas plaza, and soon after, the Ramal, or line R, between Ópera and the Estación del Norte, now called Príncipe Pio, was opened.

A young engineer who had recently graduated in Civil Engineering took part In those first construction projects, under the direction of the Compañía Metropolitana. After six years of working on the subway, José María Aguirre founded a new company with his boss, Alejandro San Román. In 1927, the construction company Agroman, Empresa Constructora was set up. The new company’s first contracts included widening the Las Arenas dam at the port in Bilbao and the railway link under the Castellana.

These also included the extension of line 3 between Embajadores and Argüelles in 1935. The first construction project that Agroman would have on the subway was paralyzed by the Spanish Civil War. The tunnels, which were left open at night, served as a refuge during the bombings of Madrid, and construction didn’t start again until 1940. On July 16, 1941, it was finally opened to the public.

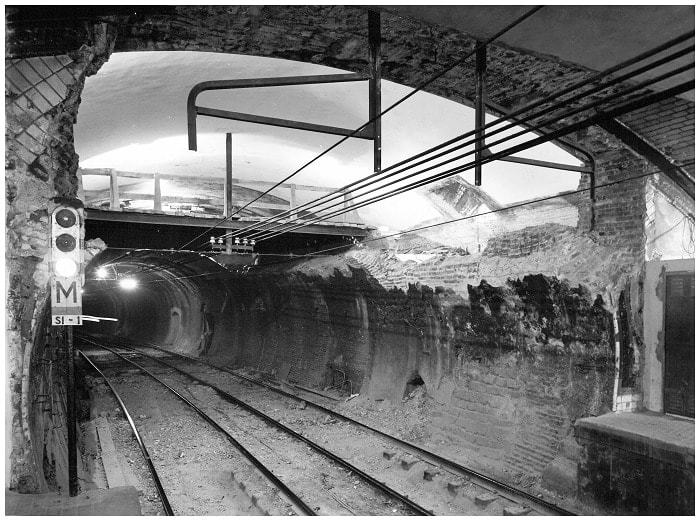

Expansion for line 4, at the Goya station. / Ferrovial Agroman

Ferrovial’s role in Madrid’s Metro

In 1944, with the opening of the Bulevares line, the subway network was up to 26 kilometers in length (still a far cry from the 154 kilometers of that first project). This route between Goya and Argüelles, now part of line 4, was also awarded to Agroman by the Compañía del Metropolitano. Then, as early as 1963 came the expansion of that first line 3, extending it from Argüelles to Moncloa.

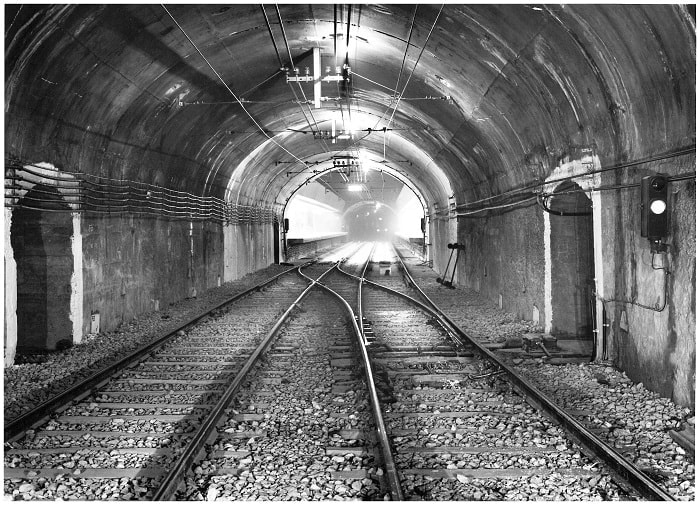

Since the end of the 1980s, the participation first of Agroman, now Ferrovial Agroman, with Madrid’s Metro grew in intensity, coinciding with a period of rapid expansion for the network. The extension of line 7 from Avenida de América to the Valdezarza station and the extension of line 1 to the Ensanche de Vallecas are among the most extensive phases of participation.

In addition, it has participated in several station renovations (including Sol, Ópera, and Tribunal). In all, almost half of the kilometers of subway tunnels built by Ferrovial Agroman were in Madrid (84,560 out of 176, 000 meters). And the company participated in construction on 88 stations, our of the 158 that it has built all over the world.

As for the Madrid Metro, it is quite different than what the Otamendis imagined over 100 years ago. It is the third-longest underground network in Europe, after London and Moscow, with 12 lines, a branch between Ópera and Prince Pio, and three light rail lines. Madrilenians and visitors no longer look on with surprise as the metro has become an essential part of the city’s backbone. But one thing is for sure: Sol has been the busiest station ever since that October in 1919. Almost 71 million travelers used it in 2018.

There are no comments yet