From Illustrious Academy to Makeshift Barracks and Headquarters of the Prado: the Villanueva Building Is over 200 Years Old

20 of November of 2019

When Diego Velázquez finished the painting Las Meninas in 1656, the other great painters of the day already knew that it was a masterpiece. What they didn’t know was that the work would eventually take center stage in one of Europe’s great art museums. And that it would still be a century before the building that would house it would be built on lands that were at the time nothing more than open meadows.

Philip IV’s dynasty, reflected in the mirror in Las Meninas, would not last many more years, either. After his son’s cursed reign and a war of succession that still echoes today, a new era of Bourbon reign would start. It brought “Madrid’s Best Mayor,” Charles III, to the throne in the eighteenth century. It was under his command that the meadows around a stream (the Castellana) became the great promenade it is today.

November 19 marks the exact bicentenary of the founding of the Prado Museum. The history of its headquarters, the Villanueva building, started long before that. But it already had a central place of the project of enlightened reforms to modernize Madrid (light, sanitation, and architectural beautification). It was designed as the headquarters of the Royal Cabinet of Natural History, and after a period as a makeshift barracks, the story of the Prado building starts one day in 1763.

From Rural Madrid to Illustrious Capital

Since the court moved to Madrid in the 16th century, the nobility had been using an area called the Prado Viejo, the “old meadow,” for leisure activities. The grassy spots known as Jerónimos, Recoletos, and Atocha were the most popular. Several streams ran through these wooded areas, including the Castellana. Over time, the Prado Viejo fell into oblivion until 1763, when the enlightened ideas of Charles III took the form of a new promenade.

Known as the reform of the Salón del Prado, the construction gave rise to one of Madrid’s main axes and shaped the Spanish capital into what it is today. The forests became gardens distributed over three sections separated by fountains (Cibeles, Neptune, and Apollo). The gardens were filled with neoclassical palaces and scientific buildings, a sign that the city was gradually opening up to an era of new ideas.

El Paseo del Prado, painting from the late seventeenth century. | Source: Wikimedia Commons

El Paseo del Prado, painting from the late seventeenth century. | Source: Wikimedia Commons

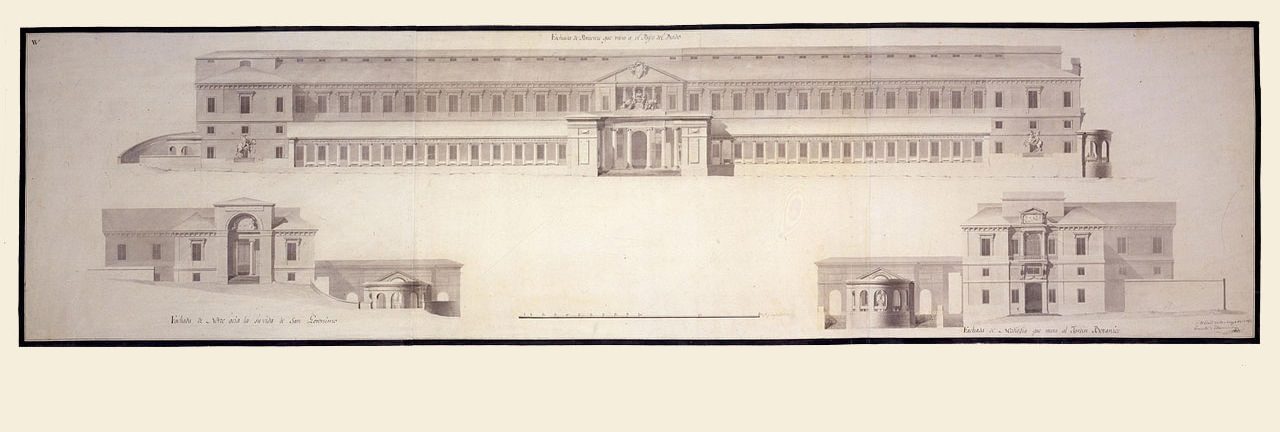

The headquarters of what was to be the Royal Cabinet of Natural History and the Royal Academy of Sciences was erected next to the Royal Observatory and the Botanical Garden. Construction of this hill dedicated to the sciences was entrusted to architect Juan de Villanueva, but this vision would never be fulfilled. Ideas changed with the turn of the century. But history reserved an important place for the Villanueva building.

Makeshift barracks and reconstruction

Construction on the Prado’s headquarters would take 20 years to begin. In 1785, the building’s first stone was laid. Charles III died soon after, and his son, who shared both his name and ideas, continued with the project. The building was practically completed in 1808, but it never opened. That year, Napoleon’s troops invaded Spain, and the War of Independence broke out.

The museum’s vaults were turned into basements to store the French troops’ arms. The building was repeatedly used as a barracks. Many of the lead sections of the roof ended up being melted into bullets. Juan de Villanueva died in 1811 in the middle of the war, having seen his work torn apart.

Charles IV had been deposed after the Mutiny of Aranjuez, and his son Ferdinand VII had taken the throne after the war. But things had changed. Enlightenment ideas had stemmed from the French Revolution and the Napoleonic invasion; politics took a more conservative turn, and everything that could be linked to France fell out of favor. Even so, there was some room left for ideas from the previous century.

The Queen, Isabel de Braganza, used her two years on the throne (she died giving birth in 1818) to convince the king to finish one of his predecessors’ projects. The idea of creating an art museum had already been on Charles III’s mind as well as that of Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon’s brother and the king of Spain during the war. After one of Villanueva’s disciples rebuilt the building, the National Museum of Painting and Sculpture was inaugurated in 1819.

The main facade of the Prado Museum. | Source: Wikimedia Commons

The main facade of the Prado Museum. | Source: Wikimedia Commons

200 years and millions of visitors

The museum’s first showing had 311 paintings, all by Spanish painters. Still, its walls already held 1,510 works from the Royal Residences and the crown’s collections. This was the seed from which one of the most important art collections in the world grew, including masterpieces such as Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, El Greco’s The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest, Ruben’s The Three Graces, and Velázquez’s Las Meninas, which had finally found its home.

It was not until May 1920 that it was renamed Museo Nacional del Prado. In its first 100 years, the building underwent a host of renovations and amassed new works of art. Since it was founded, more than 2,300 paintings and many sculptures, prints, drawings, and decorative pieces have been added.

From its start as a modest museum, the Prado has become one of the most visited in the world. According to The Art Newspaper’s annual list, it was the thirteenth most-visited museum on the planet in 2018. More than three and a half million people came through the Prado’s doors last year. And many more surely passed by the iconic Velázquez door that Villanueva envisioned (and whose most recent restoration Ferrovial participated in).

There are no comments yet