When Richard Craig first set foot in New South Wales in 1821, he was nine years old. He could not have imagined that in his future was a 1,500-meter-long bridge designed to support traffic from mechanical vehicles that hadn’t been invented yet. Richard had come to Australia from Ireland. He traveled with his father in search of the opportunities that other settlers had talked so much about.

He spent his childhood living with Aboriginal people and learning their language, skills that would come in handy when he was arrested for stealing cattle in 1828. His 14-year sentence to hard labor in Moreton Bay seemed far too much. So he escaped (three times). The last time, he was left for dead, but Richard Craig was actually hidden away,living with his aboriginal acquaintances.

He used those years in hiding to explore the landscape of New South Wales. He put rivers, valleys, and bays on the map, a task that finally earned him a pardon from the Australian authorities. His most significant discovery was the Rio Grande, a 300-kilometer watercourse north of Sydney that had oddly gone unnoticed by settlers. In 1839, when Richard Craig was once again a free man, the governor of New South Wales decided to change the name of the river; it was re-baptized as the Clarence.

Australia’s busiest corridor

The world has changed a lot in the nearly two centuries that have passed since the Craigs’ arrival in Australia. Sydney has turned into a city with over five million inhabitants. And the roads that led north to Brisbane, Queensland, have become one of the busiest roads in the country (about 30,000 vehicles travel on some part of it every day). All this despite the fact the Clarence River still follows the same course.

The Clarence is one of the nine largest rivers crossing the so-called PacificHighway. Until 1966, it could only be crossed by ferry on a barge whose remains can still be found. Since then, traffic has crossed over the Harwood Bridge, a two-lane cantilever bridge (to allow traffic on the river to pass) that had reached its capacity.

For a few days now, though, it has been assisted by a new infrastructure built by a consortium between Ferrovial and Acciona. The recently-opened bridge over the Clarence River at Harwood, the Clarence River Crossing, is the longest of the over 170 viaducts on the Pacific Highway. This new bridge is 1.5 kilometers long and has 36 spans with a maximum span of 43.3 meters; it also has four lanes to facilitate traffic. In addition, it reaches a height of 30 meters above the Clarence River to allow maritime traffic to pass under.

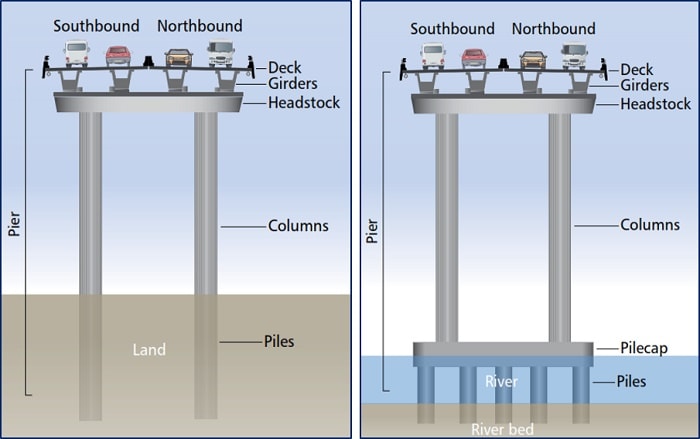

The viaduct is composed of 144 beams that weigh up to 165 tons each. And here we come to the second part of the headline, the U-beams. Each of the bridge’s two decks is resting on U-beams, or twin channel girders. They are on a single reinforced concrete headstock supported by two circular columns 2.2 meters in diameter.

The use of U-beams instead of super T beams(the most common solution in Australia) has been the key to speeding up construction times and meeting the requirements for the bridge. In two months, all of the beams were set in their final position. “The new Harwood Bridge had two huge requirements. It is replacing a cantilever bridge, so they asked us to leave a free space that is 30 meters by 30 meters in the central opening so that ships could pass under. The second requirement was for the new bridge’s piers to coincide with the old bridge’s so that they didn’t look like a slalom for the boats,” explains Eduardo Gutiérrez, a civil engineer at Ferrovial and the site’s Project Director.

The old bridge’s spans had a maximum length of 43 meters, which was a distance that standard prefabricated elements from Australia could not reach. “The solution we offered met these requirements. It covered the length, it used fewer pieces since the super-T beams are smaller, and we built the beams on site on one of the banks of the river so there was minimal interference for traffic. Because it was a prefabricated solution, this also let us lower costs,” adds Eduardo Gutierrez.

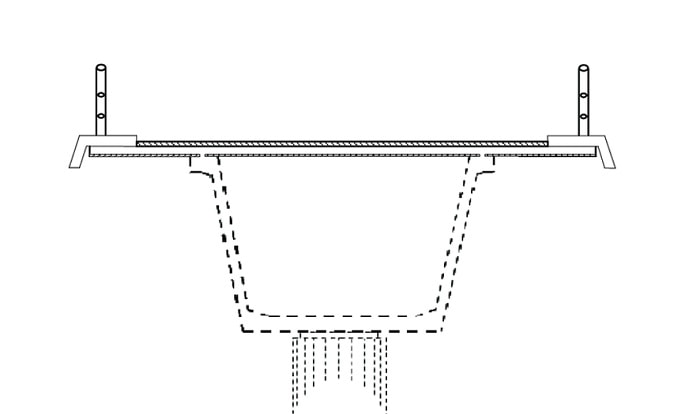

Section of a U-beam or channel girder | Author: Víctor Yepes | Fuente: UPV

Human beings have been building bridges for thousands of years. Over time, new materials, technologies, and structures have come about. Today, we have metal bridges with long spans, semi-precast concrete bridges, and even glass bridges. But as for their form (and the tensions supporting their parts), there are three major types of bridges: arch, beam, and suspension bridges.

Beam bridges, like the one that just opened to traffic over the Clarence River, are made up of horizontal elements that rest on pillars at their ends. They are under the forces of compression (the force transmitted is vertical and downward), while the beams support the forces of flexion.

Arch bridges are made up of a curved section that rests on supports and goes over a span, an empty space. The arch and pillars support compression forces, while the braces (if there are any) support tensile forces. Lastly, for suspension bridges, the deck is hung with braces from two large cables held by large concrete or steel towers. These pillars support compression forces, while the other elements are under tensile forces.

And why U beams? “It is just a wide U-shaped beam with enough depth, a prefabricated part that can support large spans. In Spain, these are very common,” the Project Director for construction on the new Harwood Bridge points out. U-beams may be pre-stressed (the cables that compress the beam and make it more resistant are stretched before concreting) or post-stressed (the beam is concreted with tubes inside that are called tendons, which are filled with cables that are stressed and cut once the concrete has set).

Beams placed on the pillars of the new Harwood Bridge. | Source: Pacific Highway

“Prestressing requires more infrastructure in the factory. In addition, from the very start, the cables go into effect, and the beam tends to curve until a load is placed on it. That is what is technically known as camber”, Eduardo Gutiérrez adds. “So for Harwood, we chose post-stressed U-beams for two reasons. Because it was more portable since it can be stressed once at the construction site, and not to increase the camber, the tonnage, which is limited in Australia.”

Ferrovial had already tested U-beams in a previous project along another stretch of the Pacific Highway, between Warrell Creek and Nambucca Heads, where they built 16 bridges and used 166 channel girders. A common solution in Spain, but one that is new for Australia. This change helped solve real challenges in a practical way. Innovation over the waters of a major river that was named Clarence 180 years ago.

There are no comments yet