A hallmark of installation art is that it so transforms a space that our experience of that space is also transformed. It inspires a deeper symbiosis with the viewer than one enjoys passively looking at hanging wall art. Even more than taking a walk around a sculpture, installation art often engages a variety of senses, creating an experience that makes the “viewer” a more engaged participant in the work.

The audience experience of monumental installation art is amplified by the public placement and large scale of the work. The artist’s creative process of selecting the site and designing the work combines with a team effort to engineer the fabrication and installation of the work. The sum of these monumental efforts is embedded in the work and can’t be separated from its impact.

A monumental installation artwork has a relationship with its location and with the people who put the sweat into installing it. The depth of these relationships, born of the extreme logistical challenges, infuse and color of the experience for everyone.

Here’s a look at three examples of monumental installation art works and their relationships with their site, materials, and engineering.

“Wrapped Reichstag” (Berlin, 1995)

The “Wrapped Reichstag” installation, which draped a historically significant German building in fabric, was the work of married artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude. The project was 24 years in the making, took two weeks to install, and remained up for another two weeks.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin 1971-95

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin 1971-95

Photo: Wolfgang Volz. ©1995 Christo + Wolfgang Volz

They began designing and modeling how to wrap the Reichstag in the 1970s. They had wrapped other objects and Christo had been conceptualizing wrapping a public government building of significance since 1961. The Reichstag is a 19th century building whose tumultuous story throughout the 20th century reflects Germany’s history. It was chosen for just that quality.

The extended and controversial nature of the parliamentary debates whether to grant the artists permission to wrap the building stands as testimony to the inherent power of the site. Permission was denied three times before a post-reunification German parliament approved the project in 1993.

The project required over one million square feet of a heavy, aluminum-based polypropylene fabric plus nearly ten miles of thick, blue polypropylene rope.

The wrapping process was as much a spectacle as the completed work. Over a two-week period, 120 installation workers and 90 professional climbers laid and folded the fabric panels on the building according to the artists’ plans.

Creative Commons Wrapped Reichstag by txmx2 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Creative Commons Wrapped Reichstag by txmx2 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Hundreds of volunteers were needed for crowd control as people flocked to watch workers rappel down the building as they wrapped the gargantuan structure.

Traffic patterns were altered. The immediate vicinity was turned into a car-free zone so people could approach the building on foot. Traffic that was normally prohibited under near-by Brandenburg Gate was now allowed so people could try to see the transformed building from their cars.

The Reichstag remained fully encased by fabric for two weeks. Five million people viewed the “Wrapped Reichstag” between June 24 and July 7, 1995. The combination of the site, the moment in time and the scale of the “Wrapped Reichstag” made viewing it a communal experience, in addition to an aesthetic one.

Yet its aesthetic aspect was indivisible from the overall effect. As described by the New York Times when the building was still only 75% wrapped,

“…this immense stone hulk, a heavy, bombastic building that epitomizes German excesses of the late 19th century, is rendered light, almost delicate. … The building is shimmering where it once was solid, refined where it once was gross and heavy. But it has lost none of its power.”

“Bending Arc” (St. Petersburg, Florida, 2020)

In Janet Echelman’s artist bio, she is described as “an artist who creates experiential sculpture at the scale of buildings that transform with wind and light. The art shifts from being an object you look at, to something you can get lost in.”

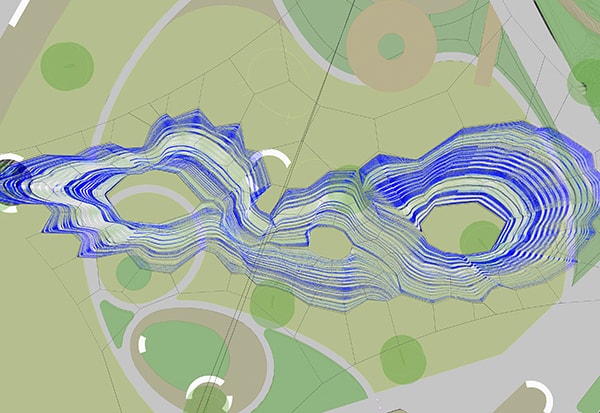

These words are also an apt description of her work “Bending Arc,” an aerial network of 180 miles (289.68 km) of knotted twine that spans 424 feet (0.13 km) above St. Petersburg’s Pier Park. Echelman, a Florida native, informed her design with familiar, local visuals: blue and white beach parasols and barnacles that attached themselves to piers.

Photograph is by Brian Adams, courtesy Studio Echelman

Photograph is by Brian Adams, courtesy Studio Echelman

Using modeling software, Echelman and her team tested out how the natural elements would impact different materials and designs. As this work was intended to hang high above the heads of people enjoying the park, structural integrity issues were as important as artistic considerations.

Two main types of materials were used. An engineered material, PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene), was selected in part because its strength doesn’t degrade with UV exposure. The PTFE was processed into an array of custom colors that react with the light. These fibers were hand-braided, and looms were used to knot the braids into diamond mesh netting. From there, hand-cut panels were hand-knotted together to sculpt the flow and dips across the work.

The rope structure created to anchor the mesh netting pieces is made from UHMWPE (Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene) fiber, the fiber used by NASA to tether the Mars Rover. The complete rope structure is 424 feet (0.13 km) by 346 feet (0.11 km). Its form was shaped using a centuries-old mariner knotting technique.

The entire work is held in place by masts, the tallest of which is 72 feet (21.95 m). Cranes were used to pull supporting ropes at the masts, creating the tension that secures the rope structure and netting.

Rendering from Echelman Studios, courtesy Studio Echelman

Rendering from Echelman Studios, courtesy Studio Echelman

Now permanently installed, “Bending Arc” undulates and billows with the winds and weather, invoking its maritime context. The mesh plays with the sunlight to present a constantly changing kaleidoscope of colors and shadows. Installed LED lights illuminate the work at night casting the monumental sculpture as magenta and violet.

Photograph by Amy Martz, courtesy Studio Echelman

Photograph by Amy Martz, courtesy Studio Echelman

The conceptual design of the work was based on the park’s nautical association, but its title was differently sourced. During the design process, Echelman learned that the park was used by locals marching for civil rights in the 1950s. As a result, she named the work “Bending Arc,” inspired by Martin Luther King Jr’s words that “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

“Bending Arc” stretches high above the public park, where it adds definition to the space below while also acting as a lens through which to view the space above.

“Seven Magic Mountains” (Las Vegas, 2016)

In the Nevada desert sits seven towers of brightly colored boulders. “Seven Magic Mountains” is a merger of land and pop art. According to artist Ugo Rondinone, it is intended to “elicit continuities and solidarities between human and nature, artificial and natural, then and now.”

Both “Seven Magic Mountain” images: Ugo Rondinone: Seven Magic Mountains, Las Vegas, Nevada, 2016. Photo by Gianfranco Gorgoni. Courtesy of Nevada Museum of Art and Art Production Fund

Also a site-specific work, “Seven Magic Mountains” does more than visually merge the artificial and natural; it sits at its crossroads. The work is located in the desert amid mountains, but is also visible from Interstate 15, the main route connecting Los Angeles and Las Vegas. The vivid, dayglow stacks, each of which stands between 30 and 35 feet (10.67 m) tall, lure unsuspecting road trippers who weren’t aware of the work’s presence.

As described on its official website, the work “offers a creative critique of the simulacra of destinations like Las Vegas.” The artificially colored boulders are all locally sourced limestone. The stacks range from three to five boulders each. In total, 33 boulders were used, with an average weight of 40,000 pounds (18,143.69 kg). The heaviest boulder weighs 56,000 pounds (25,401.17 kg).

With heavy machinery and a team from a local paving company, the boulders were moved, cut, painted, and stacked according to Rondinone’s specifications. Workers core drilled vertical shafts in the middle of each boulder. Large scale nuts and bolts were used to secure each boulder to the ones above and below it.

Among the teaching tools on the website is a lesson on “STEAM Concepts: Engineering Seven Magic Mountains.”

The work was commissioned by the Nevada Museum of Art and the Art Production Fund (APF). As the work sits on public land, numerous federal and state permits were required before it could be installed. The current land use permit runs through 2021.

Leaving the Museum Cocoon

Part of monumental installation art’s potency comes from the way it forces us out of museums. Don’t get me wrong. I love art museums. Yet they unavoidably have a “best behavior” energy. We walk through them, partly reverential, partly annoyed by the crowds, and partly annoying others as members of that crowd.

A monumental installation artwork gives us the space and permission to explore its structure and wonder at its engineering. Most wonderfully, they bring art into our everyday world instead of herding us into a more sterile environment set apart from daily life. Whether the artwork exists for two weeks or is a permanent installation, the specter of its installation and presence become part of the landscape.

There are no comments yet