Three months ago nobody was sure that the MLB would have a season. And baseball playoffs on schedule during this year of 2020? Almost unimaginable.

Fortunately for baseball fans everywhere, the game will find a way.

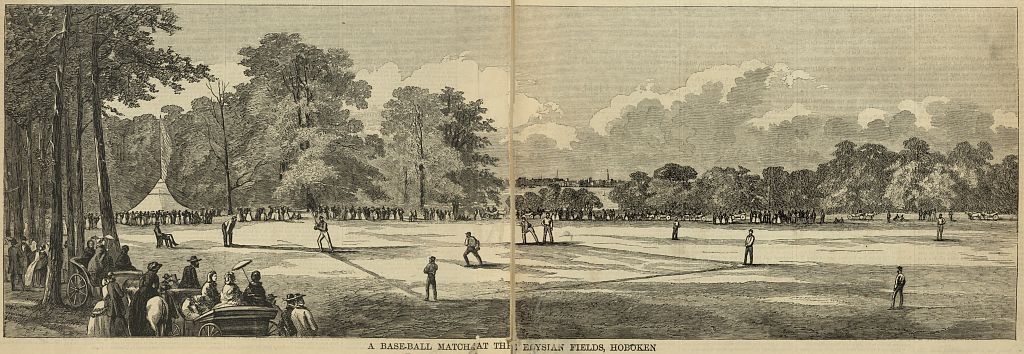

From the sport’s beginnings, the uniqueness of its individual playing fields has contributed to the spirit of the game. The first documented baseball game was played in 1845 on Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey. It was a cricket field that had a baseball diamond grafted onto it. Exact outfield dimensions weren’t a concern. Spectators had designated areas where they could stand or sit in their horse buggies.

The flexibility allowed in outfield dimensions allowed for a creativity in baseball park shapes and design across these past 175 years. A collection of baseball venues built with architectural significance for their time have since been torn down. These ghost ballparks reflected their unique place in time in the evolution of both construction methods and baseball’s growth.

Fire, Flood, and Collapse

At the dawn of baseball, teams traveled, playing anywhere they could to promote the sport. Temporary bleachers were built around a local open space. Then there was baseball and it was good.

As baseball grew more popular, it also became more economically attractive. The owner of an ice rink wanted year-round revenue and decided to turn it into a ballpark in the warm weather. Built of wood, spectators sat in crescent shaped stands that were part of the original rink. The other end of the rink was rebuilt into a large square outfield.

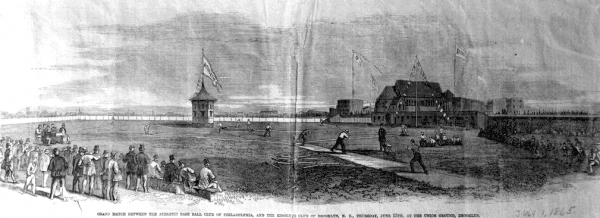

Game between the Philadelphia Athletics and Brooklyn Resolute at Union Grounds, Brooklyn (1865)

Game between the Philadelphia Athletics and Brooklyn Resolute at Union Grounds, Brooklyn (1865)

With that, the first enclosed, “permanent” ballpark was born on the Union Grounds in Brooklyn in 1862.

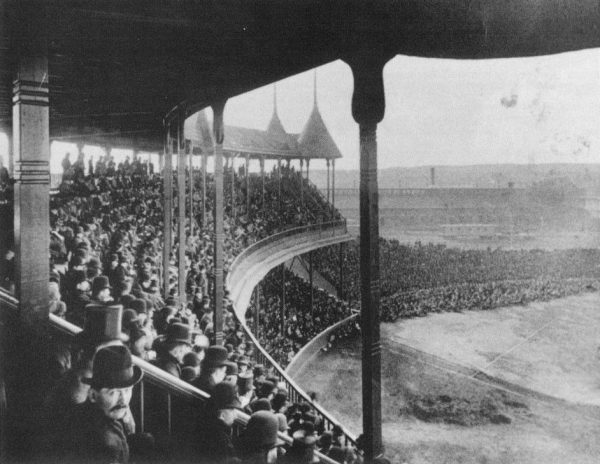

All the late 19th century ballparks were made of wood. The first park with double-decker grandstands was the South End Grounds (aka the Grand Pavilion) (1888) in Boston. As the parks grew larger, they also grew more decorative. These early parks styled majestic facades as medieval castles. Turrets and spires abounded.

South End Grounds (c 1888)

South End Grounds (c 1888)

Unfortunately, the wooden venues often burnt down, flooded, or collapsed under the weight of fans. The sport was growing.

Philadelphia’s National League Park, more commonly called the “Baker Bowl,” was built in 1887. It burnt to the ground in 1894 – except for its external brick walls. The rebuilt Baker Bowl was the first ballpark not constructed primarily of wood. Instead, it was brick, steel, and concrete. These sturdier materials allowed for the grandstands to be built with a cantilever design. Architect John D. Allen suggested the untested idea, which the owners liked as it improved sight lines for the fans at field level.

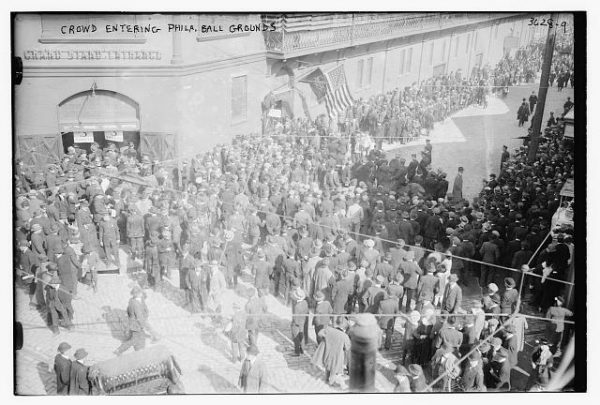

Baker Bowl, main entrance (1915), Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-B2-1234]

Baker Bowl, main entrance (1915), Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-B2-1234]

The new Baker Bowl had fifteen 30-foot iron girders that supported the upper deck and roof. Six platforms and promenades acted as counterpoise to the weight expected on the upper decks. The park re-opened to host the largest ever baseball crowd to date – 20,000 spectators.

In 1903, a wooden balcony that hung three feet over an external brick wall collapsed when 300 fans rushed into it to watch a street fight below. Despite this tragedy, the Baker Bowl’s unique cantilever technique influenced future park design. It continued to host baseball games until 1938 and was demolished in 1950.

Turn of the Century Brings a New Phase in Ballpark Construction and Design

In 1909, two new ballparks opened in Pennsylvania that defined their time.

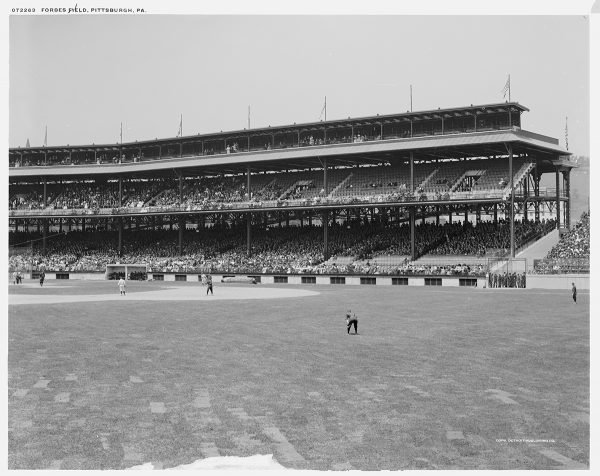

Shibe Park (Philadelphia) and Forbes Field (Pittsburgh) were built with steel-reinforced concrete, a construction material gaining popularity in the early 20th century for its strength.

Instead of turrets, the new decorative style was more neoclassical. Shibe Park’s facade had arched windows separated by Ionic pilasters. Baseball-themed friezes adorned external walls. Each park added new use spaces to the park. Shibe Park has a restaurant. Forbes installed a third deck with elevator access to “luxury boxes.”

Grand entrance to Shibe Park, c. 1913, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number LC-USZ62-79895]

Grand entrance to Shibe Park, c. 1913, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [reproduction number LC-USZ62-79895]

The urban growth of the early 20th century impacted the design and location of many parks of that era. The location of Shibe Park was chosen in part due to its proximity to public transportation. Forbes was built in a high traffic spot along the Allegheny River, home both to earlier ballparks to Pittsburgh’s current MLB park.

The outfield dimensions for parks varied due to the shape and space of the city blocks around them. Shibe’s centerfield was 515 feet (ca. 157 m) deep, while Forbes’s was “only” 462 feet (ca. 141 m) deep. (Today, MLB park center fields average around 400 feet deep.) Unusually shaped outfields of varied sizes became a hallmark of the urban neighborhood parks of the time.

Forbes Field, c 1910, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, [reproduction number LC-D4-15634]

Forbes Field, c 1910, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, [reproduction number LC-D4-15634]

Shibe Park came down in 1976. Forbes Field was demolished in 1971, but a portion of its left outfield wall still stands as an annual pilgrimage site for fans.

The Rise of the Concrete Donut

The era of the indistinguishable concrete donut stadiums, also called “cookie-cutter stadiums,” began in the 1960s. There was an explosion of these circular, heavy, multi-sport coliseums throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

The proto-concrete donut was the first Yankee Stadium, built in 1923 in the Bronx. The original plans called for a triple-decker grandstand that completely encircled the field. That didn’t happen. Yet, its grandstands did extend farther around the outfield than in any previous park.

The huge concrete and steel structure mostly held to the traditional ballpark “pizza-slice” shape, but a bit more rounded due to all the additional seating and concourses. The main entrance aligned with home plate at the “point” and then widened as it extended into the outfield. It was the first ball field to call itself a “stadium.” To misuse a Crash Davis quote, Yankee Stadium “announce[d] its presence with authority.” It was demolished in 2010.

Aerial view of Yankee Stadium, c 1928

The original concrete donut is Houston’s Astrodome, completed in 1965. When it was built, it stood in stark contrast to the open air, neighborhood parks. Dubbed “The Eighth Wonder of the World,” the Astrodome was the first completely sealed, domed sports venue.

Aerial view of the Astrodome, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, [reproduction number LC-DIG-highsm-14180]

Aerial view of the Astrodome, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, [reproduction number LC-DIG-highsm-14180]

At the time, its dome was the largest clear span dome (642 feet / 195.68 m) ever constructed. Intentionally designed to appear futuristic, the Astrodome resembles the landing of an alien spaceship. It is massive with six levels of seating. The top of the dome is 208 feet (63.4 m) high.

As the first domed ballpark, it was also the first with air-conditioning. A feature greatly appreciated in humid Houston. Because it was sealed, natural grass didn’t do well there. Thus was spawned the dreaded Astroturf. Varieties of fake grass were used in the raft of copycat concrete donuts built after it.

The Astrodome hasn’t hosted a baseball game since 1999. Due to its innovative architecture and engineering, it’s listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It remains vacant and unused.

As a class, the concrete donuts were noted for their ugliness and lack of personality. Most of them have been torn down. Indeed, 21 of MLB’s 30 active ballparks were built after 1992. This new era of baseball field design is another story, one that’s modern but with distinctive echoes of the past.

There are no comments yet