The History of the Metro: 160 Years of People Getting Around Under Cities Worldwide

25 of April of 2022

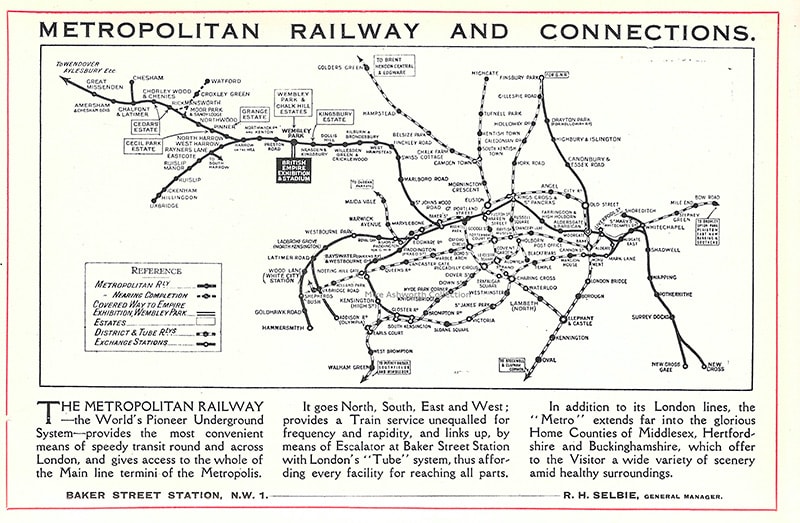

The Times called the 1863 opening of the first line of the Metropolitan Railway, which would come to be known as just the “Met” or “Metro,” “a great triumph of the engineering of our time.” It’s usually attributed to the inexhaustible obstinacy of Charles Pearson the original proposal to make getting around easier for the capital’s residents. The city’s streets – which still didn’t have cars, as they were yet to be invented – were crowded with people, horses, carriages, and even ox carts for transporting goods. That first line was just a little over 6 km of underground line, but it made history.

Underground trains

William Gladstone, directors and engineers of the Metropolitan Railway inspecting the line (London, 1863)

Of all the details about how the London Underground was built over 150 years ago (the link includes a great TED talk we highly recommend), there are two particularly interesting facts:

The first is the reason why metro lines usually run parallel under roads. They were originally built by the method of “digging and covering,” consisting of deepening the open-air road, erecting an arch with bricks for the cut-and-cover tunnel, and finally covering the rest with the previously excavated material.

The second is that this method ceased to be useful because there were too many basements, sewers, pipes, electrical cables, and other elements below the surface. So tunnel boring machines began to be used at greater depths, starting at about 25 or 30 meters. The front excavated a circular section and could advance much faster through rock and all kinds of materials, even under rivers. Today, we call those machines TBMs (Tunnel Boring Machines). This second method and its resemblance to the tubes is where the alternative name of “tube” for some metros around the world comes from.

International expansion

The Metropolitan Railway and its lines and stations (London, 1925)

What came to be called the London Underground would soon be joined by other networks in various cities. The first in continental Europe was the Budapest Metro (Hungary) in 1896, followed by the Paris Metro (France) in 1900, Berlin’s U-Bahn in 1902, and the Madrid Metro (1919). Meanwhile in the United States, the New York subway emerged in 1904, as did Philadelphia’s in 1907. The Tokyo Metro dates back to 1927, and the Moscow (Russia) Metro opened in 1935. The first in South America was the Buenos Aires subway (Argentina) in 1913; the Cairo Metro (Egypt) was Africa’s first in 1987.

It’s difficult to cover the entire chronology of the metro’s expansion, which has merged with trams, elevated trains, and commuter trains in many places. Data on this mode of transportation changes every day; in short, we know that there were at least 204 cities in 61 countries with an underground metro system in 2021:

- New York has the highest number of subway lines and stations: 36 lines and 472 stations.

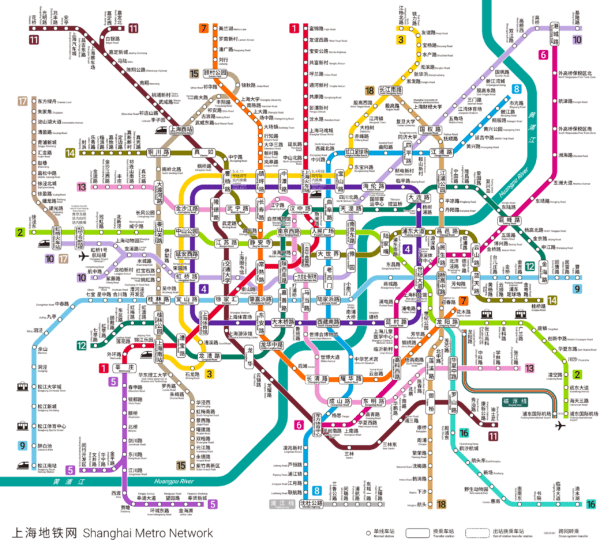

- The largest network is in the Shanghai Metro, covering 802 kilometers.

- Shanghai and Tokyo are neck and neck for the record of most passengers: about 8 million on average every day.

- The underground station that’s farthest below the surface is Arsenalna in Kiev, 105 meters below ground level.

The advent of electrification

The London Underground’s steam locomotives gave off unpleasant and harmful fumes filling the tunnels – they even stained people’s clothes with carbon particles. The switch to power lines was made in 1890. Many of today’s metros use direct current (DC) systems between 600 and 3,000 volts; others use alternating current (AC) from 15 to 25 kV.

The current usually powers the train’s motorized cars (not all have a motor, depending on the setup) by overhead wires hanging from the ceiling. There are two kinds: one that’s similar to what trams use, and the other is rigid. The type used depends on whether the tracks only run through tunnels or run outside, as well. In some metro networks, a third rail or lane is used next to the other two used by the trains. Due to its characteristics, this rail uses direct current, but the method is falling into disuse given its drawbacks – primarily the risk of electrocution for people and animals, and because it requires wider tunnels. This system was used until 1982 for some of the Barcelona Metro’s lines.

The metro in Spain

Eight cities in Spain have a metro, and more than 100 million people use these every month. Madrid has the largest network: 317 stations, 292 kilometers, 12 lines, and one branch line, serving 627 million passengers a year. Barcelona is the next biggest, with another 12 lines covering 166 km, serving about 355 million passengers. The newest network is the Granada Metro, with 26 stations on a single line; it opened in 2017.

The metros of Spain are home to real historical jewels that remind us of what this mode of transportation was like in other times. There’s Andén Cero, a “ghost station” (Chamberí) that was abandoned at the beginning of the 20th century. Then, there’s the old Power Plant at Pacífico, built in 1922 to power the capital’s metro network with the energy from three gigantic 1,500 HP diesel engines described as “Titanic.” They generated 15,000 volts that were then converted to 600V (DC) – 1.1 KW, more or less. This system would last until 1950 and closed for good in 1972. A fun fact that’s unthinkable today: these engines were supposedly always left running – even when the metro stopped at night – because it was cheaper to let them idle than to stop them for hours and start them again. This solution, while practical, was noisy and bothersome for neighbors. It has been completely restored and is now preserved as a historical museum that’s open to visitors.

A whole world underground

Shanghai Metro Plan with its 18 lines.

People all over the world use metro networks every day. Those who are most passionate about the difficulties and stories that come up underground can recognize the world’s metros by the stations’ architectural and decorative styles, by the train cars, and even by the shape of the escalators. Most would say that the Moscow Metro (Russia) is the most beautiful, with its air of grandeur. It even has gigantic chandeliers and stained-glass windows. London’s “Tube” (England) is perhaps the most iconic and recognizable, with its endless escalators lined with ads, the cylindrical stations and cars, and signs like “Mind the Gap,” as well as its unusual station names.

Another spectacular metro is the Tunnelbana in Stockholm (Sweden), which is full of works of art. Some consider it to be a real museum for visiting and enjoying. We also can’t overlook the one in Tokyo (Japan), where the massive influx of people and workers helping squeeze travelers in like sardines are also very recognizable, in addition to endless vending machines of all kinds. For art lovers, there’s also the Athens Metro (Greece), which has major exhibitions of walls, sarcophagi, urns, and everything found during the excavation work.

Metros have been getting people around all over the world for more than a century and a half, and they will happily continue to do so in the near future. In addition to their practical purpose, many also appreciate their subtlest cultural and artistic details.

1 comment

28 of May of 2025

All World metro systems