At the Crystal Palace Exhibition in New York in 1854, a man climbed on a wooden platform that hung several meters above the ground and asked for the only rope holding him to be cut. When it was, the panicked screams of curious attendees quickly turned into a huge ovation.

”Safe,” the man proclaimed calmly from the platform, which had only fallen a few inches before being stopped. His name was Elisha Graves Otis, and he had one goal: to show off his new anti-drop safety system for elevators. With this invention, Otis transformed the history of elevators and, with it, that of construction.

Along with other elements like steel and concrete, elevators made the construction (and habitability) of large buildings and skyscrapers possible, forever changing the way we understand and get around in cities.

From Rome to Versailles: the history of the elevator

The first references to the elevator’s ancestors (with systems similar to those of forklifts manually operated with ropes) date back to the ancient world. They take us to the works and inventions of Greek Archimedes inventor and Roman engineer Vitruvius and to the design of platforms that lifted objects, likely construction materials and tools.

In Rome’s Colosseum, a building that has several stories and a complex network of tunnels and dungeons in its basements, elevators were essential. They were often used to transfer convicts, gladiators, or animals (such as lions and tigers) from the lower floors to the amphitheater’s arena.

Centuries later, the architects of the Palace of Versailles also devised a system for vertically connecting different floors of the building. History tells us that King Louis XV used it to go from his chambers to those of his mistress, Madame Châteauroux.

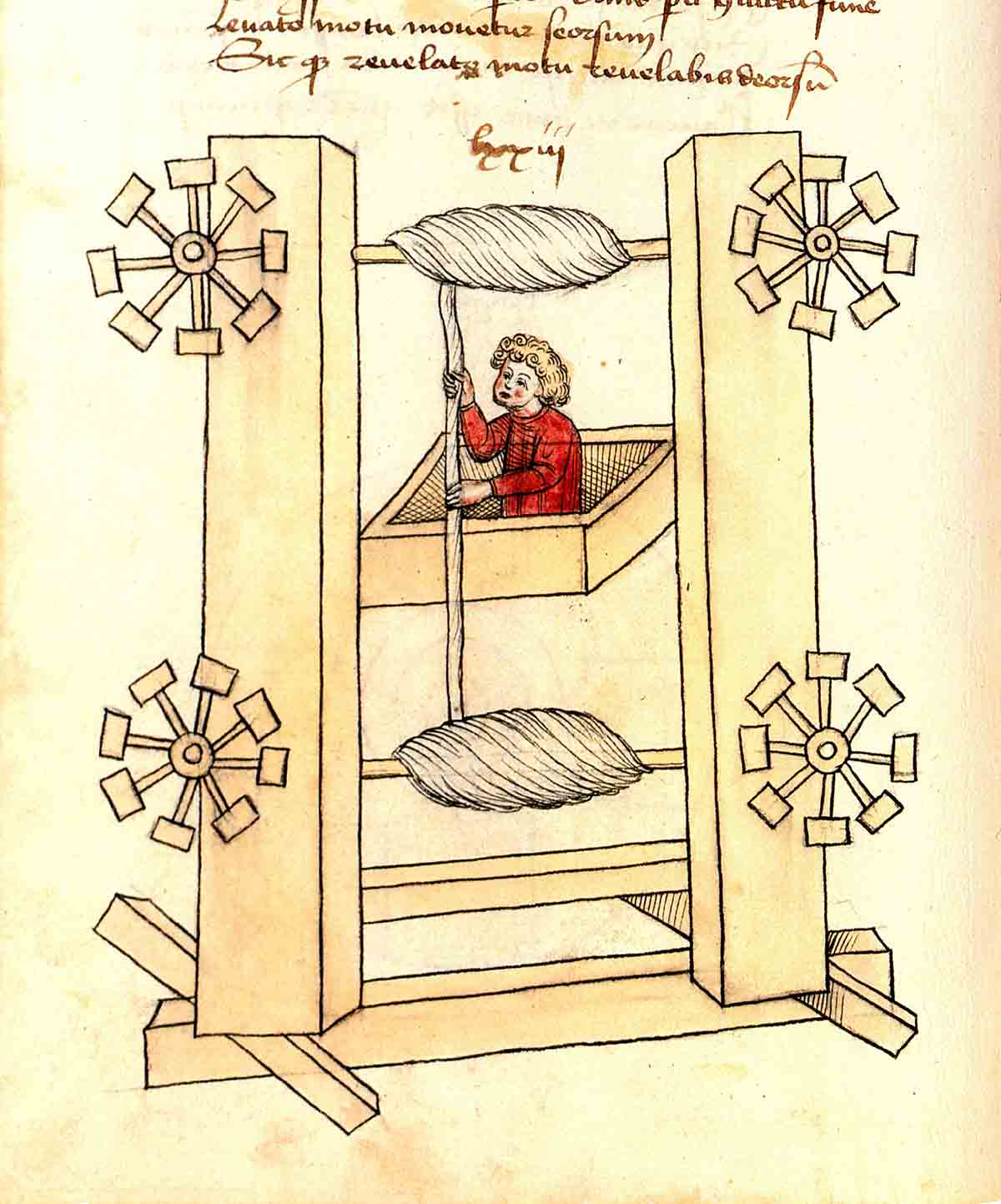

Image of the elevator designed by engineer Konrad Kyeser in the 15th century. Gun Powder (Wikimedia Commons)

It was a fairly basic mechanism that moved due to a counterweight and was operated by the king’s servants. The idea hadn’t evolved much since the ancient world: at that time, people didn’t have much interest in climbing into a small box that could save them a trip up a few stairs but also posed the danger of a significant fall.

The different prototypes that were emerging – all based on rope systems, pulleys, steam, hydraulic power, or similar to those of cranes, to name a few – were used to transport materials in construction sites, mines, or shipyards, for example. Elevators that would enable people to climb several stories vertically without fear of an accident did not become popular until the mid-nineteenth century, after Elisha Graves Otis’s contribution.

The Otis Elevator Company

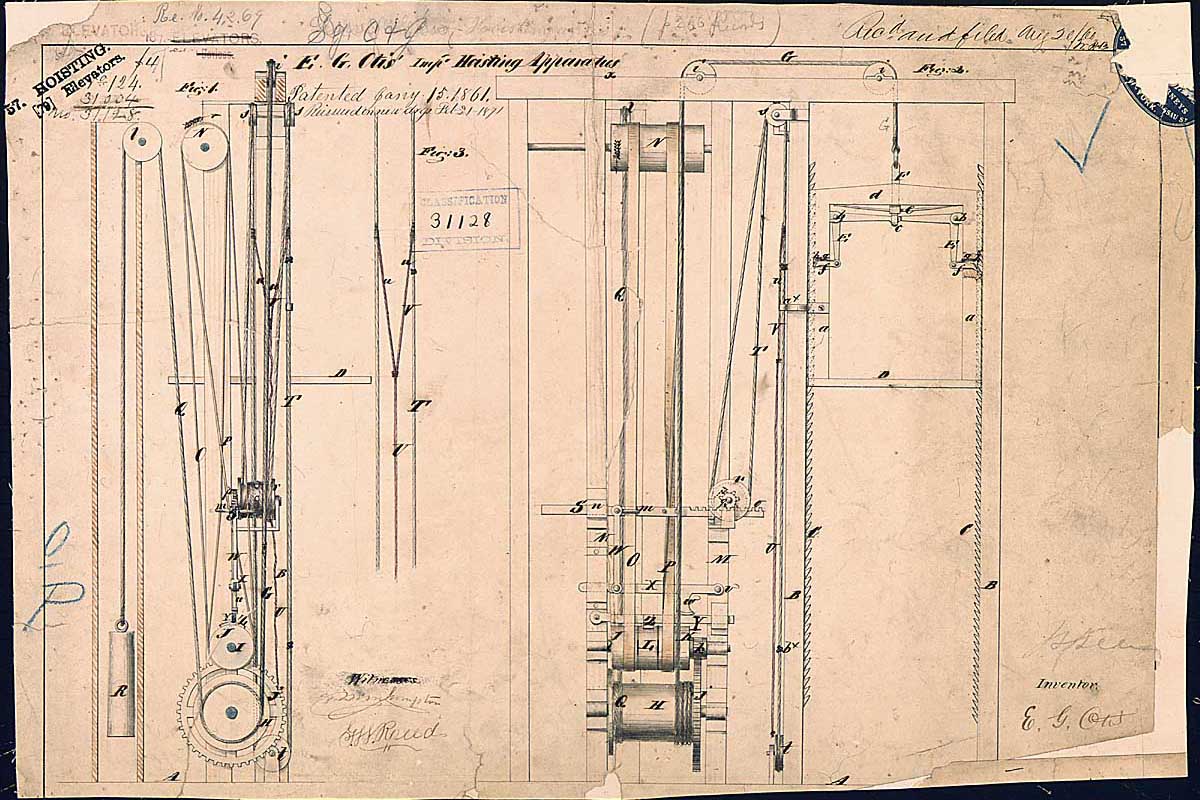

Elisha Graves Otis was born in Vermont (United States) in 1811. After going through different jobs and cities, he began working on a different assignment: to create a new factory in Yonkers (New York State). It was then that, among many blueprints and sketches, he devised the system, which included a security system.

This was based on a toothed mechanism that opened and hooked to the elevator shaft in the event that the rope holding it broke. Unlike those that existed at the time, it ensured that its users didn’t end up falling into the void for meters until finally crashing to the ground.

Elisha Graves Otis’s elevator design as it appears in his patent. Pil56 (Wikimedia Commons).

Convinced of the future of his idea, Otis opened a factory and founded his own company, the Otis Elevator Company. However, during the first few months, he barely managed to sell two. He had to show that the elevators were safe, and his eye-catching performance at the 1854 New York Crystal Exposition worked.

In a few short years, his elevators began to be commonplace in many buildings in New York and, soon after, in cities around the world. The company installed its elevators in such iconic buildings as the Eiffel Tower, the Empire State Building, the Petronas Towers, and the Burj Khalifa. However, their creator did not live to see this: Elisha Graves Otis died from diphtheria in 1861 at only 49.

The elevator that changed the world

The Otis safety mechanism meant the expansion of elevators and was a turning point in the history of cities. First of all, it made it possible for taller buildings to be built: walking up stairs and moving heavy objects was no longer such a problem, so cities began to grow not only horizontally but vertically.

The New York skyline is one example of how elevators transformed cities. Chase Baker (Unsplash)

With this change, large commercial areas also began to spring up; there, elevators transported both goods and workers and customers from one floor to another in a simple, comfortable, fast manner.

They also went about transforming the hierarchy of cities and housing. As explained in the podcast Lift Going Up by the BBC, before the elevator revolution, the upper stories of any building were considered the worst. You had to walk up to them, they were closer to the roof, and they presented many more problems than those on the ground floors.

With the elevator, this changed: they became more interesting spaces within reach of very few people. Their disadvantages became a thing of the past, and the positives started to be valued, such as the clear views and natural lighting. The elevator became a status symbol for a few years. It was a luxury item that not only elevated you to your floor but also in society.

Elevators are also a fundamental part of the design of many buildings. Sung Jin Cho (Unsplash).

In fact, the first elevators were an excellent attraction in hotels and shopping centers. In 1858, according to the BBC, many customers came not only to shop but also to try out this new mode of transportation that enabled them to climb (slowly, of course) up to five, six, even seven floors with no effort.

Today, we hardly give elevators a second thought. They only cross our minds when they are out of order, when some technical novelty arises, or when their creators promise us new services, such as cable-free cabins that will move both horizontally and vertically. However, if we take a look at our cities, we can’t help but wonder: what would our world be like today without the elevator?

Main image: Mahad Aamir (Unsplash)

There are no comments yet