It’s very likely that the theme of transportation has come up in a heated family discussion, and for a few years now, electric mobility’s autonomy and its relatively low environmental impact has shaken up the market and added new participants. During such discussions, you’ll hear things like, “Electric is the only way,” or “Nothing’s going to replace diesel.”

Other statements crop up, as well, leaving very little room for debate: the subway is the best mode of transportation; well, I prefer the bus; sure, but leave me and my bike alone; I just want to go everywhere by car… Who’s right? Is anyone right? What will the future of transportation and mobility be? Even while entrepreneur Robert Colangelo discussed types of farming, when he was asked if vertical farming would be the future for harvests, he remarked:

“I think it’s part of the future […]. Twenty years ago, vehicles ran on gasoline. Now let’s take a look: we have hydrogen-based vehicles, electric models that you plug in, hybrids, diesel, low consumption….” Everything has its niche.

We could add LPG and CNG to his list, but there are also heat engine models based on gases recovered from waste, even high-efficiency vehicles with turbines and different types of heat engine motors and even different electric motors. And we still haven’t run out of types of cars. This all seems to indicate that the future of transportation is mixed and very diffuse, particularly when we consider different types of mobility.

The supply of transportation is always improving

If we go back a few decades, we could divide mobility into four main groups: road, train, plane, and ship, in order of highest to lowest use. Roads, in turn, offered travel by bus, car, and motorbike, on the one hand; and on the other, trains, planes, and ships offered different types of tickets based on the quality of travel, business and tourist.

At present, 61% of Spaniards use cars in their normal routines, according to the 2017 Mobility Forum, 57% walk, and 46% use the bus. Subway (22%), bicycle (10%), and train (9%) are far behind them, but they’ve notably been gaining ground on cars in recent years and the market is becoming more even.

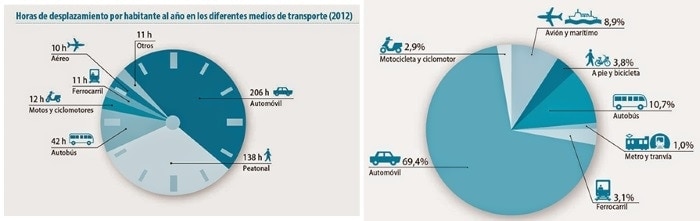

Even though it’s not directly comparable to the data we’ve just given (which doesn’t add up to 100% because we don’t always use the same mode of transportation and use more than one), we can compare it on the surface to the number of hours spent in transportation per inhabitant in 2012 (left) and with the distribution of the modes of transportation by distance traveled in 2014 (right). Both charts from MAPAMA.

The type of transportation chosen is changing, and it’s happening very quickly, but so is the way in which these modes of transportation are used. For example, years ago a plane ticket could be business or tourist class, while today there are all sorts of premium tickets, low-cost ones, and a rather long classification of seating: business with and without restrictions; tourist with and without restrictions; space for groups; tour operators, etc.

The same applies to ships and trains (silent trips, tickets with tables, a Wi-Fi option), but the true revolution we’ve witnessed is in shared private mobility. More cities have fleets of shared vehicles for rent by the minute (MaaS), and the supply is spreading out so much that it’s difficult to follow the trail.

A diffuse supply starts in cities and slowly spreads out to interurban mobility

As of January 2018, an X-ray of the city of Madrid (one of the cities in Spain with the greatest growth for MaaS) shows us a market composed of 2,500 cars, 1,500 of them electric vehicles belonging to fleets like Zity’s; 1,200 motorbikes, almost all of them electric; and around 3,000 bicycles, 1,560 of them municipal. It turns out that tracking the supply is complex because the landscape is changing every few months, something which benefits residents.

Without leaving this city, we can find three large vehicle operators with a fourth arriving in 2018, as well as five large motorbike operators. But where we really see an explosion is in bikes: BiciMad was launched in 2014; Donkey Republic, oBike, Mobike, and Ofo in 2017. It is estimated that there will be ten to twenty operators throughout Spain in 2018.

Beijing and other Chinese cities that are worried about pollution in cities where 99% of vehicles had heat engines have been making advancements in this area for years, and European cities like Amsterdam, Paris, Berlin, Barcelona, and Seville have followed their example. For example, Ofo delivered 110 bikes to Madrid, which seems to be the perfect testing ground because of its hills, and after its success the company decided to install no less than 1,000 bicycles in Granada.

Source: Pixabay | Author: Rober Allman

The increased supply benefits users, who see the price drop and service improve due to competition, but it also modifies urban traffic, which has to adapt to the new form of mobility, which is more punctual and aimed at ridding the city of vehicles. Additionally, better supply and distribution of options is better suited for the type of trip to be made.

For example, bicycles are intended for use by one person, as well as a good part of the motorbike fleet, which sometimes includes two helmets (which are, of course, obligatory). There is a two-seater carsharing fleet with a small battery, another with four seats and a medium battery, and a third with five seats and 300 km of driving range. This gives way to tiered transportation that, in the last case, is capable of traveling on interurban roads for day trips.

The changing habits of New Yorkers and other North Americans

At the start of the 20th century, New York became the megalopolis par excellence, and the introduction of the automobile made the bulk of transportation separate out into two types of mobility: metro and car, from which the yellow taxicabs that still run the roads today emerged.

However, New York and other major American cities like Chicago, Washington, and Boston are adapting to progressive change thanks to new technologies and easier urban adaptation among urbanites as well as those who are from outside the city. We can even say they’re “copying” our ideas, as in the case of Barcelona’s super-islands that Vox magazine knew to include in this video:

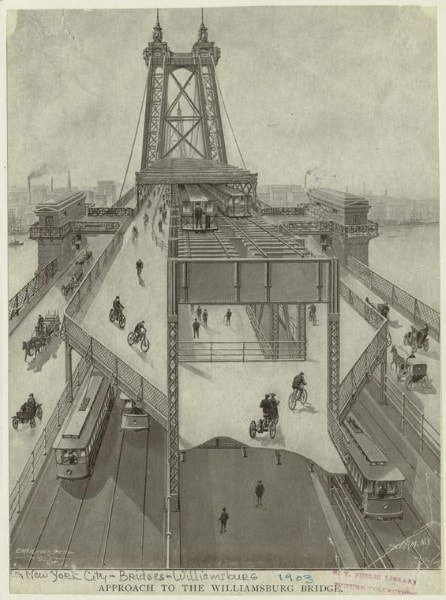

Pedestrianization isn’t the only case we’ll find in big cities, which are also opening up to another type of mobility, as previously mentioned. For example, the Williamsburg bridge (seen below circa 1903), which links Manhattan with Brooklyn, has seen 800% growth in cyclists over the last 25 years, which the NYC DOT monitors every day

Source: The New York Public Library

Another car-dependent type of mobility has come to the city of yellow cabs: Uber and Cabify have taken off with a bang, and New Yorkers use them frequently. In Europe, these companies are relatively new, having appeared in the last two or three years, but in the United States, they’ve been around since 2009, and since 2010 movies have picked up the phrase, “I’ll get an Uber.”

Central America is also improving its mobility (very slowly)

If anyone ever wants to get an idea of what traffic is, they should try getting across Mexico City at any time of day. Like Mexico, a large number of cities that have exploded in size in Central America (Guatemala, San José, Panama, Tegucigalpa, etc.) spread out over entire valleys before they understood the importance of a solid, diverse transportation system.

According to the Global Index Inrix 2017, the record for inefficiency is held by Oaxaca, with an average velocity of 5.9 km/h for cars, almost the same as a pedestrian and three times slower than a cyclist. We mention some of these cities, which are recovering from the spoils of their own success at a good pace, in order to add a key value for mobility: the speed of city growth.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The faster a city grows, the harder it is to design urban mobility plans that include more than one type of transportation. For example, Mexico’s subway is just as good as similar transportation systems in other cities, and in fact it’s received many awards for its construction and management, but it gets tripped up by an influx of travelers for which it wasn’t designed.

As a result, many Mexicans opt to travel by, which in turn jams the wide streets on a daily basis, and the bus system along with it. Due to this, numerous cities in the Americas have created so-called bus rapid transit with dedicated lanes. Acapulco, Ciudad Juárez, Mexico City, and León are some of the cities that have this system in place, which aims to be a flexible mixed mode of transportation.

Public mobility and intermodal mobility: the Medellín case

Even though some cities like Amsterdam, Santander, and Barcelona tend to become success stories as smart cities based on their mobility, the gold medal has to go to a city on the other side of the pond: the smart city of Medellín. In 1980, this city had the highest crime rates in the Western world, and in 1991 it reached the tragic record of 6,810 homicides. The city overcame this serious problem thanks to significant support from intermodal transportation and the expansion of public transit.

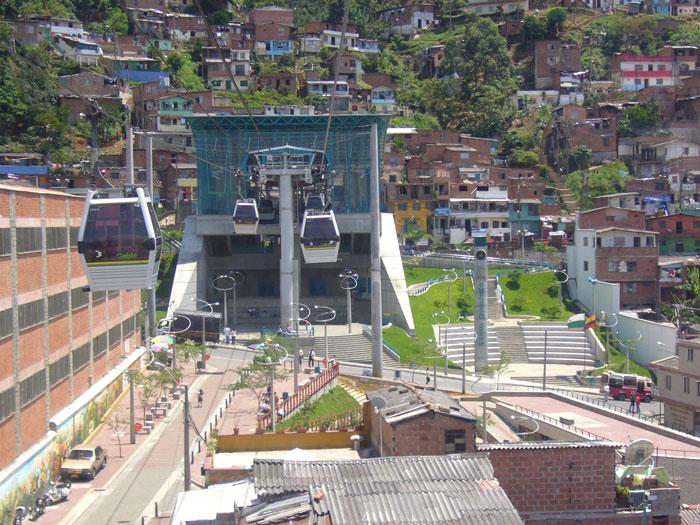

In 2004, when the term “smart city” still hadn’t caught on, the city opened the first metrocable line, a type of transportation by cable car that consists of cabins suspended from overhead wires. The idea was to link one of the poorest neighborhoods with downtown areas to avoid the concentration of crimes and to give individuals with fewer resources more opportunities. It was projected to transport about 25,000 people on average daily, but in the first month it carried more than 40,000.

Source: Wikimedia Commons | Author: Jorge Gómez

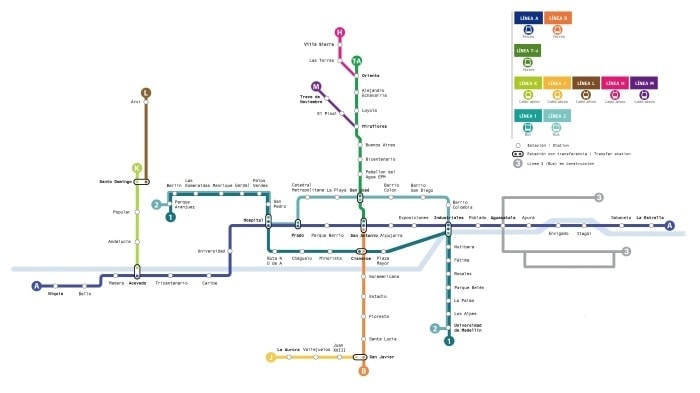

The system now has five metrocable lines (J, K, L, M, H), but what’s really eye-catching is how the city council has kept all the different modes of transportation that already existed in mind and integrated them under the same umbrella of mobility: the possibility of transferring across transit types with one ticket, called the all-in-one intermodal ticket.

That way, citizens can also choose to travel by the bus system they call metrobuses (metropolitan buses), which go all over the city; or they can change to the leading subway system, which is a little over 20 years old and is called the férreo, the rails.

.

If we take a look at the map of lines and exchanges, it shows us that the bus lines, subway, and cable cars share the same space, unlike other Spanish cities where even competition is divided up between cities or regions, and maps, when there are maps, are independent of one another. Through these efforts, Medellín was considered to be the most innovative city in the world in 2013, competing with no less than Tel Aviv and New York.

A few years later, the city of Medellín supported having Wi-Fi in its streets, making it one of the few cities in the world that offered internet to its residents for free.

Telecommunications, the key to the renewal of mobility

The Internet and the web portals that permitted selecting your seat on the plane, train, ship, or bus were vanguard in a revolutionary change in mobility: customization and choice in the hands of the traveler. It ends up being really hard to have choices when there’s only one train per day and the seats aren’t numbered, but first the internet and later smartphone apps went about changing the way we see transportation.

With the arrival of BlaBlaCar in 2006, and by using the then-novel smartphones, users could choose their preferred route and times, as well as the driver and even the price of the cost-sharing mobility service. In 2018, apps like Zity’s allow us to choose what car we want to reserve on a map based on proximity or its battery charge.

Since all the Renault ZOEs in the fleet have GPS, we also have a map that guides us through the city, enabling us to use these vehicles to get to the next train station. Telecommunications are the basis on which new mobility is being built, part of the Fourth Industrial Revolution or Industry 4.0, which is geared toward services.

In the last 10 years, mobility has changed more than ever before. The market is now very spread out and adapts to the needs of each user, not only in general but from hour to hour. That’s why it’s unlikely for one mode of transportation or technology to take the lead over others, and why the future of transportation is probably mixed.

There are no comments yet