The history of maps begins with the desire to know our planet. Throughout the centuries, travelers and explorers recorded the Earth’s shape, oceans, and features to orient themselves and travel to remote places.

However, maps have not always been as accurate as they are today. Initially, notes were made from studying the heavens and paying attention to the position of the sun and the stars. Later on, we could use mathematical criteria, measuring instruments, and cartographic techniques that improved their precision.

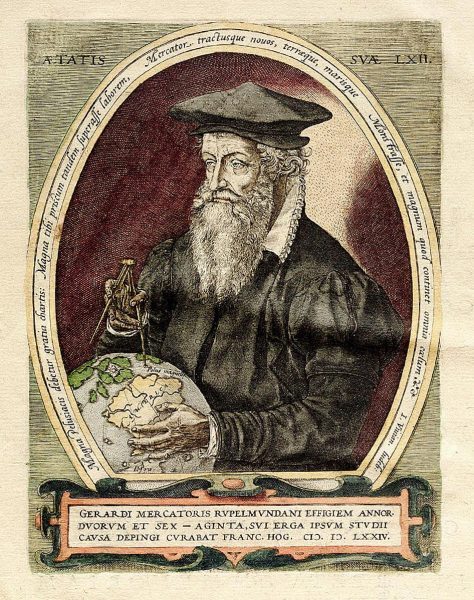

In the history of maps, one name in particular must be mentioned along with the Babylonians, Greeks, and Arabs: Gerardus Mercator. This individual optimized representations of the Earth with a method still used today.

Transatlantic voyages and a mapping workshop

Gerard de Kremer was born in Rupelmundo, Flanders (present-day Belgium), on March 5, 1512. He would later Latinize his first and last name. Kremer means “merchant” in Dutch, so he became known as Gerardus Mercator.

He spent much of his youth studying fields like mathematics, geography, and astronomy; over time, he also became interested in cartography and music. For a time, he devoted himself to engraving and mapping, which gave him the wonderful opportunity to get acquainted with the challenges and shortcomings of these tools.

At the beginning of the 16th century, maps featuring latitudes and meridians, similar to those we have today, we already in use. However, because they did not account for the Earth’s curvature, these two-dimensional lines confused navigators as they moved away from the equator.

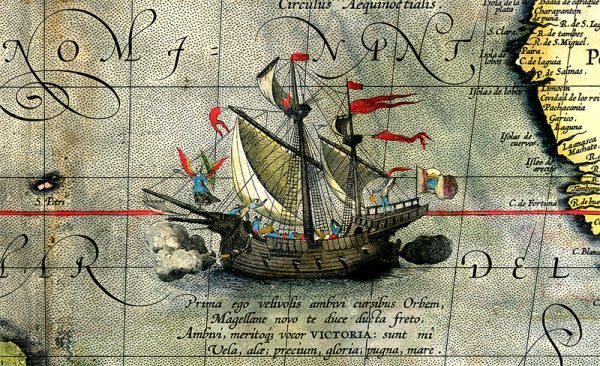

This was especially problematic at a time when trade was expanding all over the world and Magellan and Elcano were going on voyages in attempts to discover unknown shores. Maps were used to locate cities, trade routes, and major markets. Therefore, it was necessary to come up with a method that would make it possible to represent the curvature of the Earth on a flat surface.

Detail of a map showing Magellan’s ship Victoria on his expedition across the Pacific Ocean. Wikimedia.

Detail of a map showing Magellan’s ship Victoria on his expedition across the Pacific Ocean. Wikimedia.

The Mercator projection

The solution that the Dutch cartographer came up with was to increase the distance between the parallels proportionally as they approach the poles. This way, the meridians look like vertical straight lines that intersect the parallels at right angles. This made it easier to draw routes. To navigate from one place to another, you just had to connect the departure and destination points with a straight line and keep a constant course with the help of a compass.

This method, known as the Mercator projection, gained popularity among navigators, and it ended up being promoted by different monarchs for creating nautical maps.

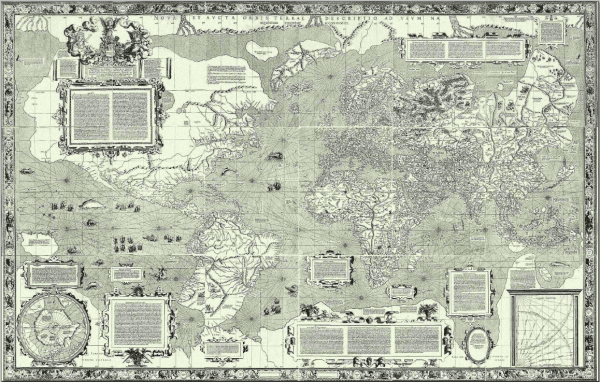

Mercator’s 1569 world map. Wikimedia Commons

Mercator’s 1569 world map. Wikimedia Commons

However, this solution also has its limitations. Unlike equirectangular or geographic projections, it does not preserve the distances between the parallels. As a result, maps drawn with this principle show the continents’ shapes but not their sizes. Countries closer to the poles look proportionally larger than those at the equator. Thus, these maps give the false impression that Greenland and Russia are as vast as Africa or South America.

This has often been pointed out as perpetuating a Eurocentric worldview. However, it is unlikely that this was Mercator’s goal: his main concern was addressing a problem that plagued navigation and orientation.

In addition to the projection that bears his name, the Dutchman made other contributions to cartography. He created maps of Palestine, Flanders, and Europe; he brought italics to map engraving (more suitable than the Gothic characters then used); he was the first to use the term “atlas” for a collection of maps.

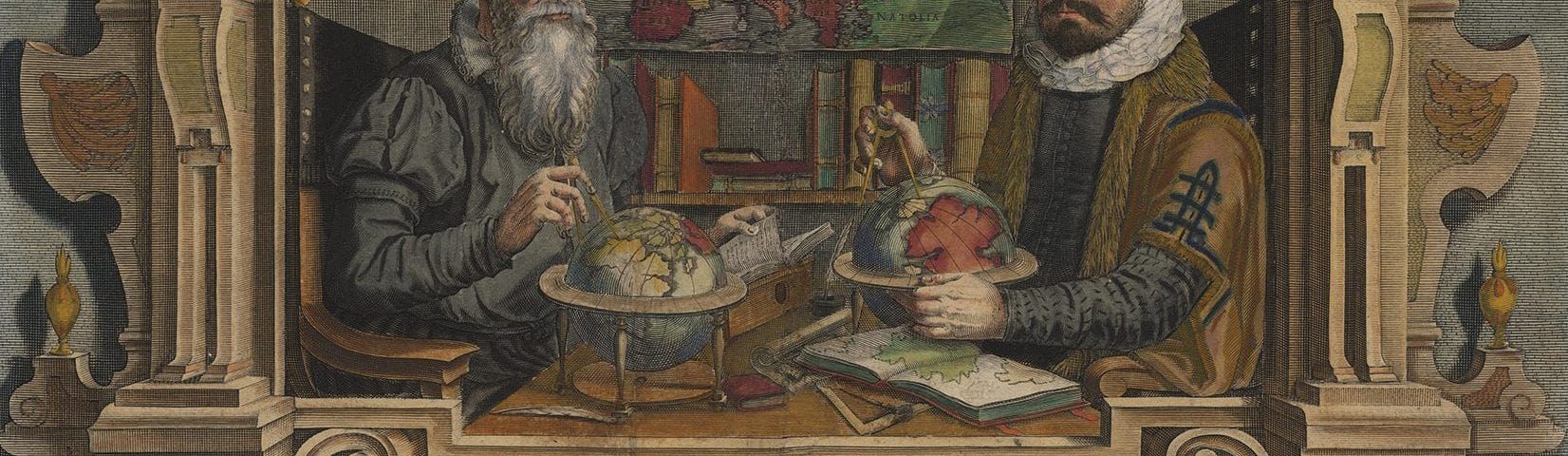

Painting by Frans Hogenberg of Mercator pointing to the magnetic north pole. Wikimedia Commons

Mercator died in 1594 in Duisburg, present-day Germany. He left Flanders years earlier after being accused of heresy and spending seven long months in prison.

From the internet to smart cities

Mercator’s way of projecting the Earth changed the way maps would be made forever. Even though other methods and more map projections emerged over the next few centuries, the Dutchman’s projection is still used today. Apps like Google Maps and Bing Maps are based on that method’s principles, though they have minor variations.

Today, maps are much more than a representation of the Earth. They offer complementary information, they’re updated almost constantly, and they’re used for so much more than just navigation. Soon, they will also be essential for developing Smart Cities since they offer a large amount of data that can be used to redefine cities. A 16th-century cartographer certainly couldn’t have imagined these uses, but they still depend on projections from that time.

There are no comments yet