In 1840, there were just over 5000 kilometers of railroad tracks connecting the United States. Just three decades later, that number had increased by almost 10-fold. By the end of the century, there were enough steel tracks to go around the planet a dozen times.

At that time, the world was also growing vertically. Buildings had more and more floors, and the first big skyscrapers were beginning to be built. The industry was growing, and with it, so was the consumption we know today. Behind these changes was a clear trigger: the invention of a method of producing steel in large quantities, and much more economically, that was invented by British entrepreneur and inventor Henry Bessemer.

A lifetime of inventions

Henry Bessemer was born in 1813 in the county of Hertfordshire in the United Kingdom. Before he turned 17, the young man had already left school to focus on his father’s business: a type foundry where they worked with different metals. It was there that he began to look for improvements in the industry and build his first inventions, such as a machine for making bricks and a method for optimizing the formula for the materials they worked with.

In the following years, Bessemer created and patented all kinds of methods and devices: mobile dies for stamp printing, machinery for extracting sugar from sugar cane, a brake system for railway carriages, and even aerodynamic wagons. The list goes on to reach at least 129 patents and many other inventions he never registered.

In 1853, when the world was marked by imperialism and colonialism, the Crimean War broke out. At that time, Bessemer became interested in the conflict and began working to make British weaponry more efficient, safe and, above all, lightweight. He patented a rifle shell and an artillery mortar, but the British government didn’t take any interest in them. The French did, though, and they commissioned the inventor to build several experimental shells.

However, everything that Bessemer presented was too heavy, and doubts arose about whether the French artillery could withstand its use. Everything pointed to the fact that improving weapons and creating new options would require producing steel faster, cheaper, and more abundantly. So he got down to business.

A revolution in the world of steel

In the mid-19th century, when Bessemer began to investigate new ways of working steel, metallurgy was based on traditional methods. The industry was based on knowledge that had been passed down for millennia, and many of the scientific aspects of its components were unknown.

In addition, metal production was a slow, complicated, and expensive process. It took almost a month of work to produce just over 22 kilograms of material. This led numerous inventors and entrepreneurs to try to create techniques to speed up the process and make it cheaper; they knew that whoever achieved this could transform the world.

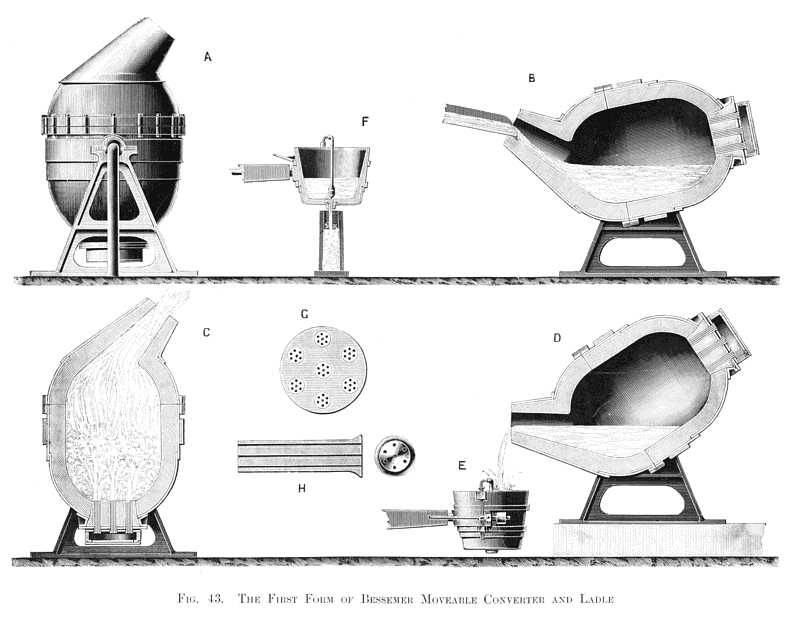

Bessemer won this race when, in 1856, he patented a method based on oxidation. He created a converter that let oxygen into the molten pig iron to oxidize the metal and reduce the number of impurities. In addition, the air injection raised the temperature of the substance and kept it liquid longer, which made it possible to save on the fuels used in furnaces.

How the converter works. Wikipedia

This allowed the materials to be mixed in the smelting tank at constant temperatures and in sufficient quantities to cut costs. “All this resulted in getting steel in large quantities (25 tons) very quickly (in 25 minutes). This was why the furnace was called a ‘converter:’ it transformed pig iron into steel,” the Virtual Museum of the Spanish Patent and Trademark Office (OEPM) explains.

Bessemer’s Converter at the Kelham Island Museum. Chemical Engineer (Wikipedia).

Bessemer’s new method was revolutionary in the industry. Steel was no longer limited to manufacturing small objects (such as tools, cutlery, and machinery parts); it could also be used in large quantities in construction, the railway sector, or, as was first intended, for weaponry.

Thus, one of the first objects created by Bessemer with his first furnace was a pistol, which he presented to Napoleon III. Shortly after, the inventor was back to his old habit of registering patents. This time, steel was a common denominator. As the OEPM mentions, his list of inventions includes railway wheels, beams, machinery rollers, artillery shells, propellers, cranks, and many more objects.

Skyscrapers, shopping, and Christmas parties

Over time, Bessemer went about refining his method, thanks to contributions from different inventors and engineers. He founded several companies, outperformed the competition, and when the end of the Crimean War reduced the demand for steel to make weapons, he focused on other sectors, such as the railway industry.

According to records, 100,000 tons of steel had already been produced in 1865 by the furnaces Bessemer had in Europe. Mass production of this strong, flexible, light, and resistant material also transformed construction and what towns and cities looked like. Its use in structures made it possible to erect taller, slimmer buildings, giving rise to the creation of the first skyscrapers.

Steel structure. Luca Upper (Unsplash)

As mentioned in the journal American Scientist, improvements in steel production and the invention of the modern elevator boosted the economy and changed history much more than we typically imagine: “Department stores came about in these buildings, and they were central points for business that used steel rails to transport both products and customers. Due to this development in business, steel had an unusual result: Christmas.”

Before business was booming, Christmas was a minor holiday in the United States. The increase in production and consumption gave rise to the holiday season as we know it, with the spending and gifts that are so commonplace today. But that’s a different story.

Henry Bessemer’s story ended at the end of the nineteenth century when he passed away in 1898 in London. Even in the last years of his life, he was still dedicated to his inventions, such as an astronomical observatory and a diamond polishing machine. At the time of his death, the amount of steel produced using his method had already amounted to more than 11 million tons worldwide.

Main image: Portrait of Henry Bessemer by Leslie Ward. National Library of Wales (Wikipedia).

There are no comments yet