Natural areas in all regions are affected by the changes brought about by humans when urbanising large areas, or when changing land use to agriculture or industry. Roads and motorways, the marking of land with fences or the construction of tunnels can significantly modify living conditions for the wildlife population in all affected areas.

The approaches used for the protection of wildlife in areas crossed by roads stem from an increasing awareness of the importance of environmental issues. The general aim is to avoid fragmentation of habitats which leaves small, isolated areas. The simplest solutions are usually the creation of so-called wildlife crossings, which act in specific areas to protect biodiversity, with larger-scale green or biological corridors crossing whole countries or continents.

On roads

One of the traditional solutions for wildlife crossings are tunnels, viaducts and bridges. These types of constructions, in addition to protecting wildlife, avoid collisions between animals and cars, which are usually fatal for animals, but dangerous also for the people driving along the roads and motorways.

Source: zja.nl

Medium-sized and large animals, including flocks of animals, can cross specific viaducts and tunnels with no problems. Such structures are built in a size and width as to properly accommodate the flora and vegetation of the area.

Source: zja.nl

A good example is The Borkeld, by architecture studio ZJA Zwarts & Jansma Architects, which crosses the Hoge Veluwe national park in the Netherlands, through which the A1 motorway runs. The structure comprises two parts: a wider part covered with soil and vegetation through for animal crossings, and a nearby walkway for pedestrians and cyclists. This so-called “ecoduct” is also relatively inconspicuous, without even a central pillar. For drivers, it is simply a quiet extension of the landscape that runs over the road.

Tailor- made solutions

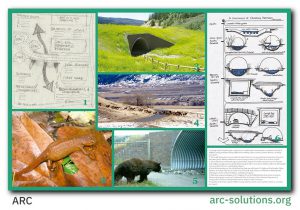

More thought is necessary, however, for other types of animals. Tunnels and drains for fish and amphibians; in countries with large areas of forest, extensive networks of cables have been installed for squirrels, monkeys and other arboreal animals. Since around 1950, when awareness on the issue began to grow and the first wildlife corridors were built in France, they have extended to every country. Some cases are particularly striking.

Source: christmas.net.au

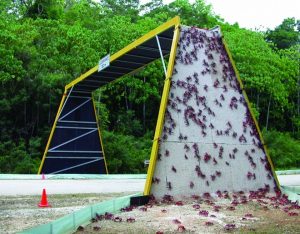

One of the most well-known wildlife crossings is the bridge for red crab on Christmas Island in Australia. The crabs live in the forest but reproduce in the sea, where they return every year to breed. Before, many would die, squashed by the cars driving along nearby roads.

Source: christmas.net.au

So, the Government built 31 underpasses, 20 km of barriers and a striking elevated bridge for the crabs to cross without coming to harm. It also made life easier for drivers, who said they had a challenging time trying to avoid the crabs. There is no longer a need to close the roads except at specific moments, and traffic can flow freely.

Another striking case is the protection of bats in the Barranco de la Batalla on motorway A-7, in Alcoy (Alicante). The area happens to be home to six species of bats – two of which are in danger of extinction and two threatened– living in the Juliana Cave in that area. Bats fly over the road to the other side, but at times they fly too low over the road in their search for prey and can become confused and at risk of being run over by the cars.

Protection in this case consisted of 300 metres of netting along the road, held up by posts on either side. The netting mesh size is such that allows the bats’ echolocation system to detect it as an obstacle to be avoided, so that they or any other birds are not trapped by it. The netting is complemented with false tunnels along the main hunting routes, and during construction works care was taken so that the bat colonies in the cave would not be affected, especially during the breeding season. A counting exercise was carried out using infrared cameras, with over 1,850 individuals detected. The netting used is dark green in colour to minimise visual impact on the landscape.

Source: ARC

Protection in this case consisted of 300 metres of netting along the road, held up by posts on either side. The netting mesh size is such that allows the bats’ echolocation system to detect it as an obstacle to be avoided, so that they or any other birds are not trapped by it. The netting is complemented with false tunnels along the main hunting routes, and during construction works care was taken so that the bat colonies in the cave would not be affected, especially during the breeding season. A counting exercise was carried out using infrared cameras, with over 1,850 individuals detected. The netting used is dark green in colour to minimise visual impact on the landscape.

There are no comments yet