What Would the United Kingdom’s Lost Rivers Have to Say About Climate Change?

01 of June of 2020

The Abroñigal is the second most important waterway in the city of Madrid, after the Manzanares. However, fewer and fewer people remember its banks. Since 1970, it has run under the M-30. To be more exact, the ring road runs over the Abroñigal channel.

Madrid’s first inhabitants settled not far from the rivers and springs that provided clean water and fishing, as most human settlements did. Today, almost all of those waterways are covered, but their waters continue to flow under meters of dirt and asphalt. Some of these rivers even survive in the city streets, like the Castellana’s stream.

However, the reasons why these rivers decided to go underground one day are no longer very important. Today, underground waterways are starting to pose more challenges than benefits. The best example of this may be the lost rivers of the United Kingdom.

The Victorian coverings of London

The Thames is one of the biggest, longest rivers in England. On its banks lies the most populous city in Europe: London. Today, the Thames and its bridges get all of the attention, but there was a time when the London flatland was a wet terrain, prone to flooding and furrowed by dozens of other rivers and streams. Fleet Street, Walbrook, Effra Road, Bayswater, and Stamford Brook were all named after the old waterways that still flow beneath them today.

The lost rivers of London are not unique. In fact, covering waterways was standard practice in Victorian England. Throughout history, rivers have been the natural source of drainage for human settlements. In other words, that is where practically all waste ends up. But during the 18th and 19th centuries, as cities grew and industrialized, the situation became unsustainable.

The rivers turned into open-air sinks, and the bad smell was hard to deal with. So before most urban water treatment systems were put into practice, the main option was covering the rivers. In exchange, there was space for new streets and city improvements.

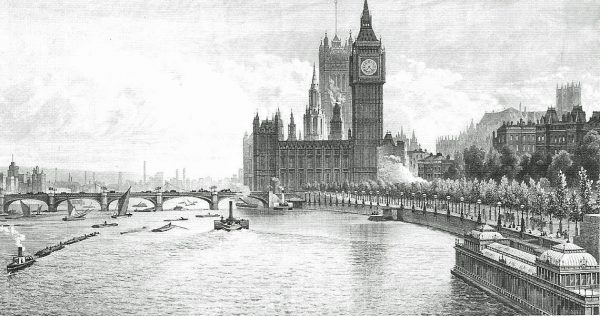

The River Thames in London, 1875. | Leonard Bentley

The River Thames in London, 1875. | Leonard Bentley

Is it time to re-naturalize rivers?

Besides London’s history, the situation happened again and again in many industrial and agricultural centers of the United Kingdom. However, times have changed since the decision was made to cover rivers in the United Kingdom and across Europe.

Today, most cities have efficient sewers and water purification systems, so the flow of pollutants into rivers has decreased across much of the continent. Furthermore, in the event of a spill through an old pipeline, it could not be found easily, as it would be hidden from view.

On the other hand, cities have continued to grow, and the layers of pavement have continued to build up over underground rivers. This requires increasingly frequent maintenance for the pipework of these waterways, which, in many cases, are the same as they were over a century ago.

Not only that, but rivers are nature’s stormwater drainage; by being channeled and plugged, their capacity is seriously limited. As sediment has accumulated in many of these channels over the years (further reducing their capacity), climatic trends indicate an increase in torrential rainfall, in both intensity and frequency, in the coming decades.

That means that underground rivers pose an increased risk of flooding in many cities today. Recovering them and bringing them back to the surface could be part of a major set of measures to mitigate the effects of climate change and build more resilient cities for the future.

In addition to all of that, there are the obvious benefits of having a natural river environment for ecosystems and people. That is why there have been more and more daylighting projects in recent years, or similarly, there is the option of uncovering and unchanneling underground rivers as much as possible.

Roch River daylighting work in Rochdale, United Kingdom. | Wikimedia Commons/P. Hogg

Roch River daylighting work in Rochdale, United Kingdom. | Wikimedia Commons/P. Hogg

The advantages of uncovering underground rivers

“Water adds to the feeling of belonging to a city, and it often turns the river environment into a hotspot for activities. Wildlife returns to the city, even if it’s just a few species of ducks,” explains David Lerner, a professor of environmental engineering at the University of Sheffield.

Along with other members of the university, Lerner has analyzed daylighting projects in the United Kingdom over the last decade, publishing the results of his research in the paper, ‘Volunteered information on nature-based solutions – Dredging for data on deculverting.’

“In the 96 projects analyzed, the main reasons for uncovering the underground rivers are the desire to create new habitats, reducing the risk of flooding, providing new amenities, and developing regeneration projects,” the environmental engineer goes on to say.

In more detail, the benefits that bringing the rivers back can offer include:

- Reducing the risk of natural disasters, particularly flooding, by increasing the natural flow of drainage from the environment where cities are located. If unchanneled, control of the flow is also improved through the terrain’s absorption capacity.

- Limiting future costs. As the costs associated with natural disasters decrease, the river’s environment becomes an asset to the city, with long-term economic benefits.

- Reduced maintenance costs Even though maintenance for an urban river is not without expenses, they are considerably less than those for maintaining underground infrastructures.

- Improving the quality of life in the area. Renaturation of the river environment involves not only uncovering the watercourse, but also improving its banks, replanting vegetation, and allowing wild fauna to return.

Recovering the Porter Brook river in Sheffield and the Roch in Rochdale, which involved recovering not only the river but also a 14th-century bridge, are some of the examples of a waterway returning to daylight in the United Kingdom after decades underground. These lost rivers have been rescued for a future that is a little greener, more sustainable, and, above all, resilient.

There are no comments yet