Once humans began writing things down around 3200 BCE, we needed storage space to hold all that recorded knowledge somewhere. The history of the library and how we organize knowledge raises a variety of issues. One of them is how the physical medium of the recorded knowledge impacted how it could be stored, organized, and retrieved. The physical design of libraries is connected with how information is categorized and catalogued, but also stands apart. As the primary medium for knowledge storage evolved, so has the design of the spaces that hold it.

Recorded Knowledge Started with Tablets

The earliest material for recording knowledge was inscribing on clay tablets while the upper layer was still damp.

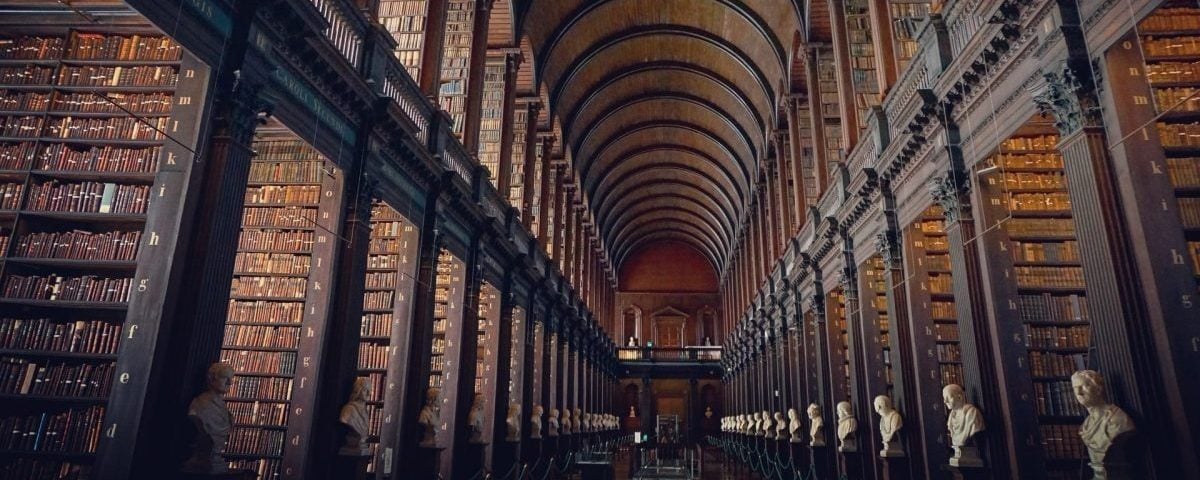

The Library of Ashurbanipal is the oldest known library to have some of its contents discovered, around 30,000 tablets and fragments. Ashurbanipal located his library on upper floors in two palaces. The library was for the king’s edification.

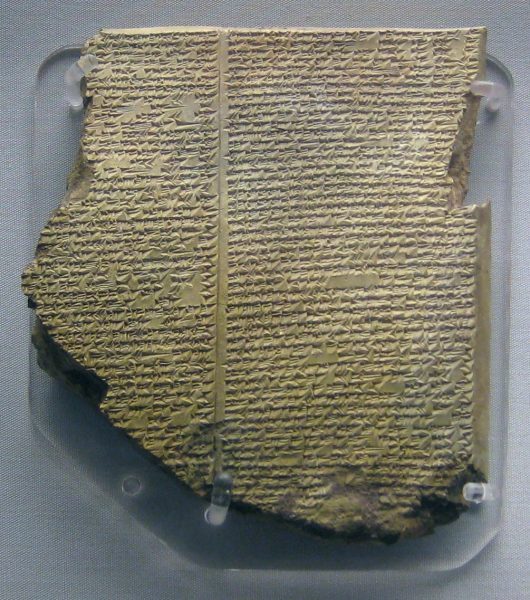

The tablets covered a wide variety of topics, such as government records, incantations, and literary works. A copy of the Epic of Gilgamesh was found among the library’s ruins. The highest level of categorization was done by room. Historical texts in one room. Astronomy in another, and so on.

The tablets didn’t have a uniform shape or size. Often, the shape of the tablet was an indicator of its contents. Rounded tablets documented crop yields and other agricultural records. Four-sided tablets contained financial records. The library did have clay shelves for the tablets, but they were also stored in reed baskets and boxes.

Fragment from the Epic of Gilgamesh describing the flood from Library of Ashurbanipal; British Museum.

Would the Great Library of Alexandria Have Been So Great if the World Still Used Tablets?

By the time the Library of Alexandria was founded in the 3rd century BCE, scrolls were the primary medium. Scrolls were popular because they could hold ink, which made writing easier than having to engrave a tablet. The materials were also easier to manipulate and carry. Different cultures turned to different materials. Around the Mediterranean, scrolls were made from papyrus or animal skins. In east Asia, bamboo and silk were used as scroll material.

The lighter, more mobile scroll made it easier for scholars to access and move them around. The scrolls were stored horizontally on sub-divided shelves. With scrolls piled on top of each, no one shelf could be too large. Yet, this also meant the shelves didn’t need to be level. A too-large horizontal shelf could be broken into four triangular sections with two smaller planks installed in an “X” shape. Tags at the end of each scroll gave the scholars needed bibliographic information about its contents. Scholars could carry the scrolls they wanted to designated study areas within the library.

The Library of Alexandria was built as part of a larger learning institution, the Museum of Alexandria. The Museum was a campus where research fellows, like Euclid, lived, studied, and taught together. It was founded to bring together the knowledge of the world. The Library is famous not simply for the size of its collection, but its worldliness. Not all its works were scrolls, but it could not have grown so large without lightweight, easily transported and packed scrolls holding so much of the world’s knowledge.

Mt. Vesuvius has provided a glimpse into how scrolls were stored in antiquity. The explosion preserved a library in private villa, now called the Villa dei Papiri for the 1000+ scrolls found there. Most of its scrolls were found in a single room. The room’s walls were lined with wooden shelves with piles of scrolls. Some free-standing shelves were in its center. The library itself had no place for people to sit. As was typical of the private libraries of the time, people would have taken the scrolls to a tablinum or peristyle to read.

The inner peristyle at the Getty Villa, which was designed with strong influence from the Villa dei Papiri; “The Inner Peristyle” by Linc Spaulding is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The inner peristyle at the Getty Villa, which was designed with strong influence from the Villa dei Papiri; “The Inner Peristyle” by Linc Spaulding is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

When Books Became Valuable, Libraries Started Locking Them Down

The precursor to the printed book was the codex. A codex used folded, bound pieces of parchment within a hard cover. The presence of a spine, with space for identifying information, improved library organization.

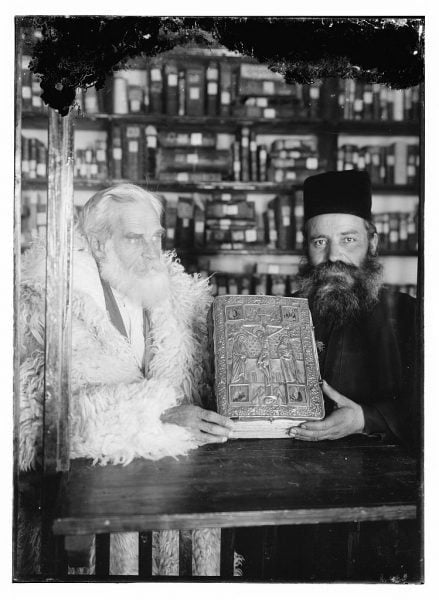

Christian monasteries of late antiquity were the first to adopt the codex to replace the scroll. One of the oldest – and still operating – is the library at Saint Catherine’s Monastery. Located at the foot of Mt. Sinai, it holds the second largest collection of codices, behind only the Vatican. The most famous codex in its collection was the Codex Sinaiticus, a 4th century CE manuscript of the Christian bible. It remained in the monastery’s library until the 19th century, when a German researcher removed it. Parts of the codex are now held by four libraries in Europe and Russia, with most of it in the British Library. Perhaps the monastery should have adopted another library trend – chaining their books to the shelf.

Sacerdotes ortodoxos griegos sostienen un códice con cubierta de plata, Monasterio de Santa Catalina (1923)

Codices were laborious to create and the materials were costly. This was true both for illuminated manuscripts and more modest codices. Books were expensive, yet mobile, assets. As more universities and churches established libraries in the Middle Ages, they needed to protect those assets. Thus was born the chained library.

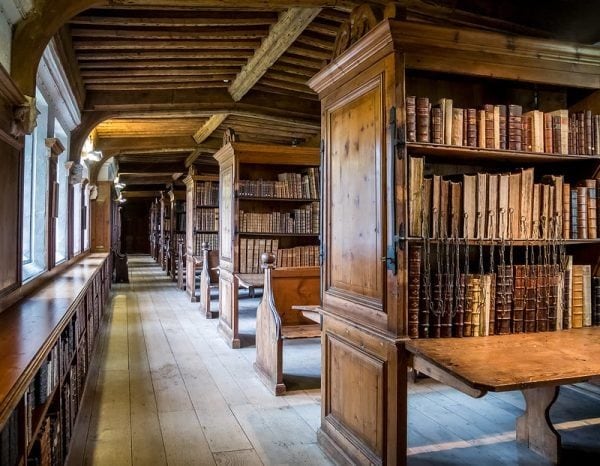

In a chained library, the manuscripts were literally chained to the shelves. Separate reading rooms were not an option in a chained library Readers had to go to the books. The interior design of chained libraries followed one of three patterns.

Reading pews: Each separate book was laid out on a long, narrow, angled reading surface that topped each pew. Readers sat in the pew in front of the pew were the desired book was located. In some cases, the back of each pew was also bookshelf. This was a more efficient use of the space as more than one book could be accessed from one seat.

Zutphen Librije at St. Walburgis Church (Netherlands); library established in 1564.

“Librije:” by jimforest is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Reading desks attached to the shelves: Bookshelves were built with narrow desks running their length, which were often hinged. This design required even less space per book than reading pews with shelving and allowed readers access to a greater number of books from a single spot. It was common for all the books on a shelf to be attached to a single rod. In order to move a book, all the books before it on the rod would have to get removed first, which put a premium on ensuring books were logically organized.

Wells Cathedral Chained Library (UK); library established in the 1450s. “Chained Library” by Matthew_Hartley is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Wells Cathedral Chained Library (UK); library established in the 1450s. “Chained Library” by Matthew_Hartley is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Readings tables placed between the stacks: While today’s libraries have most tables in a central location surrounded by some shelves, these libraries had narrow reading tables inserted in between the chained shelves.

A Look towards the Digital Future of Libraries

Digital content, e-readers, and other ubiquitous screens are changing once again how we store and access recorded knowledge. Public libraries grew exponentially in the 19th century as sharing knowledge widely advanced as a public virtue. Today’s libraries are finding that book lending is a small part of their mission as people have digital access to so much content. Spaces for book stacks are getting repurposed for computer labs, cafes, art galleries, and meeting spaces. One school library has removed nearly all its books.

Taking a different approach, the Hunt Library at North Carolina State University has kept the books but is using technology to improve its space efficiency. Its “BookBot” navigates an automated storage and retrieval system holding two million books. Because human navigation among these books isn’t required, this portion of the library’s collection is stored on one-ninth the space that would be needed for traditional stacks.

The BookBot at North Carolin State University; “NCSU Library Bookbot” by Stuart Borrett is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

The library is more than 221,000 square feet, so the BookBot wasn’t intended to reduce the size of the building’s footprint. Part of the vision of the library’s design was to increase the study space available to students. The Hunt Library has enough study seating for 20% of the student population.

Indeed, the next phase of library design may well not ignore the printed word. Talking with Architectural Digest, Meredith TenHoor, an architectural historian and associate professor at Pratt Institute School of Architecture, said that the library of the future has “a place for old-fashioned paper books,” and that their design won’t “just conceive of books as sources of information but of the social and intellectual practices that develop around reading and research.”

There are no comments yet