Whether you are a person of faith or a convinced atheist, cathedrals have that je ne sais quoi which make us feel small when we step inside them, which make us admire their columns and wonder how on earth it is possible for tonnes upon tonnes of stone to be piled on top of each other and not collapse on us, turning us into human pulp.

When we walk into a cathedral, the first thing we do, almost instinctively, is look upwards, mouth gaping in amazement, not only at the beauty of the place, but at the technology that makes it possible. And many of us fail to realise that such beauty would really not be possible without some of the elements which we consider simply a decorative object, such as pinnacles and gargoyles, but which in fact actually hold up the building.

What is a gargoyle?

For we all know, of course, what gargoyles are, though maybe not why they are there. Comic, devil-like figures which seem somewhat at odds in a place of worship but which nevertheless decorate fronts, arches, vaults and balconies, amongst others. To be fair, we should say that not all gargoyles are deformed and grotesque creatures, although in the beginning they may have been.

Gargoyles were initially simply decorative elements placed over the pipes or drains provided to channel rainwater from the roofs. To hide the drains’ rather drab appearance, architects in the middle ages adorned them with these figures. And, in addition to their aesthetic function, gargoyles helped to compress the walls on which they were mounted (but more on this later).

Segovia Cathedral, with vertical pinnacles and horizontal gargoyles. Source: Marcos Martínez

What exactly is a pinnacle?

As opposed to the original gargoyles, some of which we can see in the above photograph emerging at right angles from the cathedral front, pinnacles came into being as architectural elements to add weight to the columns on the building fronts. The reason for their decorative appearance stems from the need to conceal the half tonne of stone required to make them. And, let’s be honest, they would not look quite as nice if they were mere solid blocks of stone.

But why add even more weight to a building using gargoyles and pinnacles? Factory construction

So, gargoyles were a decorative element which hid in them some extra weight to add to the walls, and pinnacles were an architectural element for adding weight to the walls which ended up being a decorative element. But the fact that surprises us is that architects should decide to add weight to a wall, a fact that begs the question: Is that really necessary? What for?

In order to answer this question, we must first analyse what factory construction is, and how to bring it down. Essentially, factory construction is the piling up of blocks or bricks one on top of the other, so that the top block compresses the one below. A way of building which, up to a certain height and provided the piling is done properly, is very safe. The problem was the roof, a particularly useful architectural feature which avoids us getting wet when it rains. Gothic architecture tradition held that the cathedral’s main nave (the central area) should have a vaulted roof. No matter that the Greeks had solved this problem by using flat roofs, these seemed to no longer be in fashion.

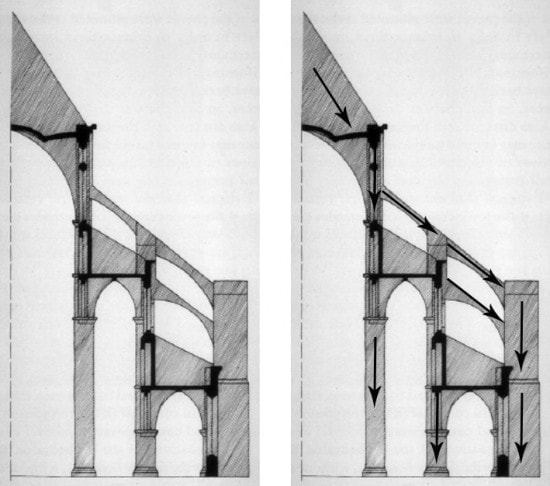

Cross section of a cathedral, and the same section showing main vector forces. Source: IES Eladio Cabañero

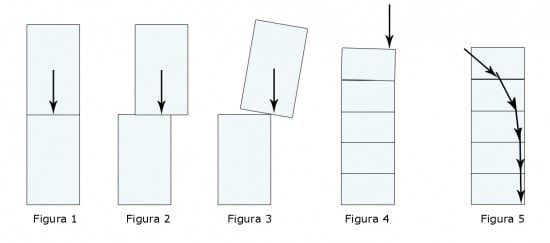

Domed or vaulted roofs had the disadvantage of pushing the walls quite forcefully outwards, as can be seen in the above section. The resulting internal vector forces made the walls collapse, or the domes and central nerve of the cathedral collapse in on themselves, dragging everything else with them. In order to understand what goes on inside a wall, take Figure 1, showing how the weight of one block compresses the block underneath it, shown as a downwards arrow. If the upper block is moved slightly to one side, the weight continues to press downwards (Figure 2); however, the upper block will fall over if its weight can no longer press down on the surface of the one below (Figure 3).

Blocks and forces. Source: Marcos Martínez

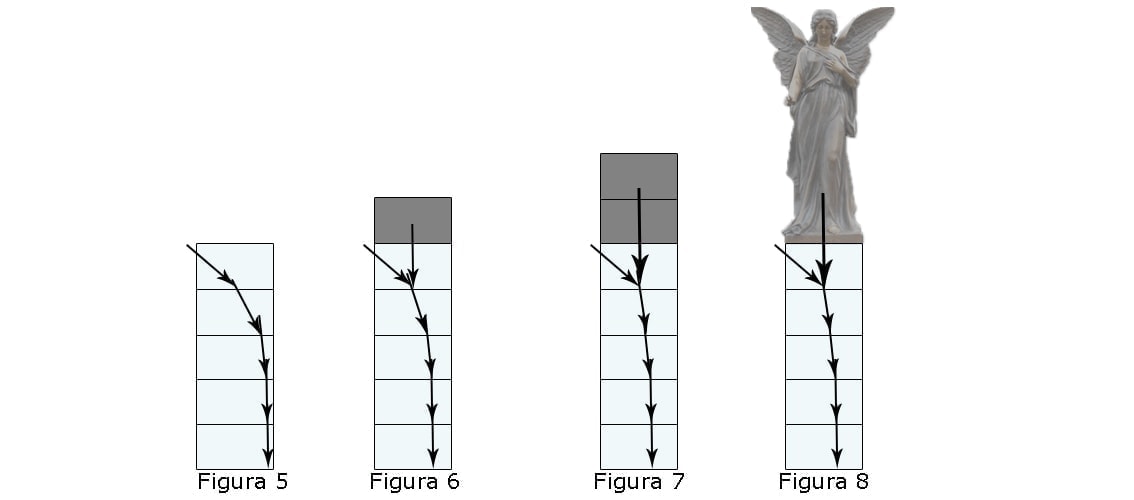

If the blocks are placed one on top of another, and a force is applied far from the central point of the blocks, we can see that they move apart at the opposite end to that at which the force is applied (Figure 4), causing the wall to crack and eventually collapse. If we transfer the vector forces shown in the cathedral section to our wall, we can see (Figure 5) that the forces are displaced dangerously far from the central point of the blocks.

So we need to do one of two things: either substitute the vaults, domes and curved roofs with something less showy (such as a horizontal slab), or find a way of distributing the vector forces differently within the column of blocks. For Gothic architects did not like horizontal slabs on their cathedrals at all.

Gargoyles, pinnacles and lead

Even before Gothic times, cathedrals had striking domes and central naves with vaulted roofs. But Gothic architects wanted their cathedrals to be much larger, which meant that the internal vector forces within the structures increased. Thick walls, secondary walls, buttresses and lateral naves were no longer enough. The building, quite simply, couldn’t cope. And it was at this point in history when builders realised (although initially they didn’t quite understand why) that by adding more weight to the columns, the vaults and domed roofs did not collapse under their own weight. This was rather disconcerting for many architects, but not knowing the reason why the central nave didn’t collapse was no impediment for applying the method throughout Europe.

Cathedral building went through a period of adjustment using trial and error. More and more weight was added to the columns until they seemed safe.True to the principle that the more weight the better, solid blocks of lead, the heaviest metal there is, have been found as pinnacles, topping the side columns of cathedrals by the dozen, and adding hundreds of tonnes in weight to the whole.

There are no comments yet