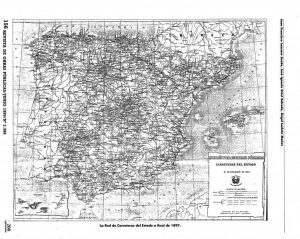

Spain today boasts a total of 165,483 kilometres of road, toll road and motorway. For many hundreds of years, however, the pathways linking villages, towns and cities were little more than narrow lanes dotted with the remains of Roman roads and engineering works. One fine day in the 17th century the decision was taken to establish and maintain a network of paved roads that corresponded to the centralised structure of the country. So important was this decision that a specialised body was even founded for the purposes of maintaining, cleaning, repairing and guarding the roads: the roadmen, or navvies (in the UK).

We have spoken about Roman roads in the past, and how they would traverse valleys and rivers with hardly any bends and offering only gentle gradients. In other words, true works of two-thousand-year-old engineering that in some cases still survive today. For centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire the road network they had established was still more advanced than any that existed between the major European cities at the time, the others consisting of pathways that had been forged over thousands of years by the passage of people and animals alike.

The Middle Ages saw new attempts to regulate and maintain the peninsular road network, and while these were merely fledgling attempts, by the 12th century the Honourable Council of the Mesta, the Castilian herdsman’s association, had made efforts to regulate transhumance (the passage of cattle) and the dimensions of the pathways, establishing a maximum width of 90 varas, some 75 metres. The Catholic Monarchs and the Habsburgs also oversaw both the establishment of new roadways and the protection and maintenance of others of import, such as the Camino de Santiago, also known as the Way of St James.

Subsequently, however, a series of illustrious ideas began to arrive from France and the Bourbon Monarchs decided it was the right time to establish a network of paved roads, or, roads with a top layer of gravel or crushed stone that helped strengthen the underlying structure. This may be considered the birth of the current national radial road network.

Image: Durcal local council archives

The new road network

“The construction and conservation of roads is of the utmost interest to any government, and as such should be a constant consideration. Given the success and opportunity afforded by these works, the establishment and conservation of a proper internal communications system would appear essential […] as it is the only way to provide an outlet for agricultural and industrial produce”… thus begins the chapter dedicated to roadmen in the General Guide to Postal Services, Coaching Inns and Roadways, written by Francisco Xavier de Cabanes and

By the mid-18th century works were already underway to unite Madrid with Andalusia, Catalonia, Galicia and Valencia. If necessary, mountains were levelled (tunnelling was still in its infancy), marshland was drained and bridges were built. “At this juncture few roads are left to be built, or require large-scale, costly repairs”, predicted Francisco Xavier de Cabanes, unaware that subsequent centuries would see no end to the building of infrastructures.

For the design and construction of these roadways an extensive team of civil engineers, architects and surveyors was established. Once finished, a roadmen’s guild, or corps, was established for the purposes of guarding and maintaining the network. This entity was important enough to be awarded the right to bear a flag; a distinction that, in those days, meant they were allowed to arm themselves with carbines. The figure of the roadman would survive almost to this day.

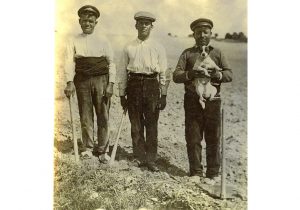

Image: Fernando Cana

A life on the road, for the road

“For the immediate and continuous conservation of the roadways, there has been established therein, league by league [a little over 5.5 kilometres], a body of labourers bearing the title of roadmen and wearing shoulder pouches, who have been entrusted with carrying out, in the league assigned to them, any refurbishments that may be prescribed”, says the mandate approved by Ferdinand VII in 1824; a document that would clearly establish the role of the roadmen.

- Maintain the road surface. Even out carriage tracks with stones or gravel. Fill in potholes and prevent the road becoming mud-bound.

- Ensure that the road is always covered in gravel, a compound of small, rounded stones.

- Free the road and the shoulder of large stones and rocks.

- Clean the ditches and trenches as well as the drains so as to avoid flooding.

- Fix and report any damage done to the road.

- Travel the road and be alert every day, whatever the weather, from sunrise to sunset. The only absence allowed was one day a month, when the worker was allowed leave to collect his salary.

- Keep an eye on and detain unsavoury characters or those with the appearance of miscreants and bring them before justice.

Image: Pixabay

The lodge: an enduring symbol

Over the course of the 20th century roadmen’s conditions would progressively improve. The section they were expected to guard and maintain was shortened and a few hours of rest was allowed every day, especially during the summer months. An awards system was even established, with an annual prize of 50 pesetas going to the best employee. The most notable improvement, however, came about in 1852 when it was established that each roadman would be entitled to a small house and a slice of arable land on the stretch of road for which they were responsible. These buildings were called casillas [small houses] in Spain, and some still survive today.

“The lodge should preferably be located on high ground that affords a view of the section of roadway. There should be abundant water both for individual hygiene purposes and for maintaining the surroundings, as the lodge could be surrounded by woodland in order to make life more comfortable for the roadman and his family, especially during the hot summer months”, explains Elena de Ortueta Hilberath, a lecturer at the University of Extremadura. In addition, the majority of these lodges were decorated with tiles indicating the distance to Madrid.

Regulation of the profession continued throughout the first half of the 20th century, when the number of roads increased and the arrival of the automobile brought with it a change in road maintenance requirements. Roadmen now had to pass an exam to prove their reading, writing and arithmetic abilities as well as their knowledge of the regulations concerning the circulation of automobiles and the conservation of roads.

Image: Priego de Cordoba’s Municipal Archive

Between 1950 and 1960 the number of privately-owned cars tripled and the road network was obliged to undergo changes in order to adapt to the increase. Furthermore, the arrival of heavy machinery changed the way road maintenance was carried out. The work carried out by the new machinery and operators, however, did not differ much from that which the roadmen had been carrying out for more than 200 years, that being to prolong the useful life of the infrastructures, allowing them to carry out the same functions as that for which they were originally designed by the Romans so many centuries ago.

There are no comments yet