For decades, cities around the world increasingly allotted streets to vehicular use, squeezing out sidewalks. Sidewalks grew narrower, the number of parking spaces spiked, and green spaces were paved over. Nowadays, the general trend has turned to put that reality in reverse. And there is a silver lining: even the least pedestrian-friendly city has features that enable strolling through it.

To celebrate World Pedestrian Day, which many cities observe on August 17, we’re going to look at the innovations that have made cities friendlier and safer for those of us getting around on foot.

Pedestrian crossings

Though it is difficult to pinpoint when pedestrian crossings were first used and marked out, all indications suggest that they date back to the time when wheeled traffic first became a part of city life.

One of the oldest surviving remains are those of the Roman city of Pompeii: they include a system of raised blocks that allowed pedestrians to cross the street without walking directly on the roadway.

Pedestrian crossing preserved in the ruins of Pompeii. Xerti (Wikimedia Commons)

Pedestrian crossing preserved in the ruins of Pompeii. Xerti (Wikimedia Commons)

Later on, modern cities started using signs to designate these crossings. The first to be painted on the ground with white stripes was in the English town of Slough. That was in 1951. When the Beatles took the picture that would become the cover for their famous album Abbey Road, crosswalks as we now know them were barely 18 years old.

In the decades that followed, overpasses were built to connect sidewalks. These signaled a shifting mindset. As extensions of the sidewalks, they allow pedestrians to stay above the road. The possibilities of smart crosswalks or 3D ones, and even perhaps even interactive ones, have also been the subject of recent investigations.

Traffic lights

Traffic light in Bologna, Italy. Luca Tacinelli (Unsplash)

Traffic light in Bologna, Italy. Luca Tacinelli (Unsplash)

The history of modern traffic lights begins in the offices of the British railway system. There, engineer John Peake Knight noticed the signs used at train stations, and he thought they might prove useful for directing pedestrian and vehicle traffic in cities.

At that time, the 1860s, London’s population was growing, and so was its traffic. The engineer’s idea went through a pilot test. In 1868, after being in development for three years, the first traffic light between Great George Street and Bridge Street was installed. The device was large in size, measuring over twenty feet high. It had arms that indicated when traffic should stop. At night, red and green lamps were added to enhance the system.

Just a few weeks after the traffic light was first up and running, on January 2, 1869, a gas leak caused an explosion, injuring the policeman on duty. The initiative was abandoned in London, but over the next few decades, similar projects were implemented in the United States.

As the years went by, traffic lights began to feature three lights (green, yellow, and red) and were electrified. Today’s crossing lights have countdowns, animations, and even smart features. IoT connectivity is expected to equip traffic lights to collect data in the coming years. This will enable optimizing traffic flow in cities and lowering the number of accidents.

From the railway to the cable car

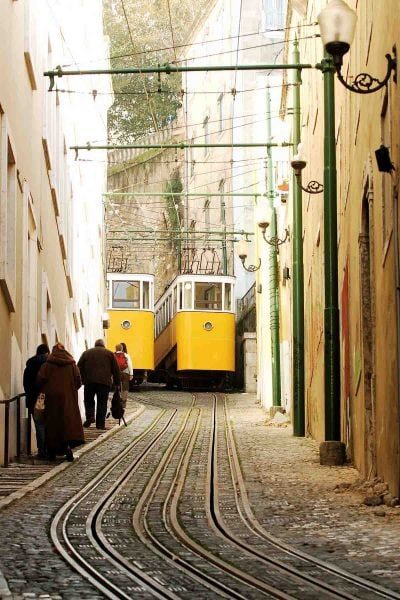

There is one thing that many cities have in common, from Lisbon to Medellin, Barcelona, Vigo, and San Francisco: hills. Such slopes make it hard to get around in the city. They lead people to depend on public or private transportation rather than walking, and they can deepen social inequalities.

With railway systems developing, numerous cities around the world began to install lifts and cable cars. This is the case with Lisbon, for instance, and its do Lavra, da Glòria and da Bica lifts. The oldest of the three at da Lavra was designed by Portuguese engineer Raoul Mesnier du Ponsard. It opened in April 1884.

The Elevador do Lavra in Lisbon. Pedro Simões (Wikimedia Commons)

Spain’s first cable car went into operation seven years after that, in October 1901. To this day, it connects Barcelona and the Tibidabo Amusement Park.

The latest interpretation: escalators

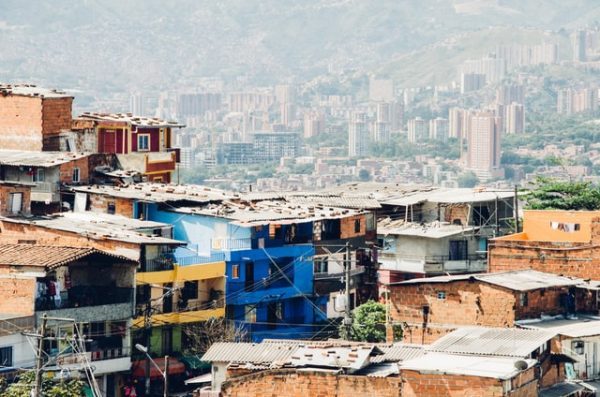

In recent years, these lifts have gotten some additional help from escalators. This is especially true in cities with a large elderly population or where the slopes make daily life harder for residents. One of the most notable examples is in Medellin (Colombia). These moving stairways were part of an ambitious plan to end the violence and inequality of the previous decades.

There, the stairs connect the heart of the city with the surrounding hills, including areas like Comuna 13. This part of the city was especially plagued by violence from guerrillas, paramilitary forces, drug traffickers, and finally, the gangs born of its streets. Today, it is a symbol of the city’s transformation. The Las Independencias neighborhood (the meeting point for all of the escalators) is the second most touristic spot in the entire city of Medellin.

Photo from the highest neighborhoods in the city of Medellin. Milo Miloezger (Unsplash)

Photo from the highest neighborhoods in the city of Medellin. Milo Miloezger (Unsplash)

A second life for sidewalks

Last on the list of all these changes is pedestrianization. This gradual process begins with the sidewalks and spreads to the rest of a city’s spaces.

Several ancient cities (again, like Pompeii) had sidewalks that were slightly raised off of the roadways, allowing pedestrians safe passage among horse-drawn carts. However, medieval cities had narrower streets, and this form of separating pedestrians from wheeled traffic was lost.

In the 1480s, Leonardo da Vinci came up with an ideal city that was stratified into different levels, separating trade and transportation from residents’ lives. His vision never came to fruition, though. It wasn’t until major reforms where carried out in cities like London and Paris in the 18th and 19th centuries that sidewalks regained some importance in urban development.

A street in Paris. Zdenek Klein (Unsplash)

A street in Paris. Zdenek Klein (Unsplash)

Today, many cities are planning to do away with sidewalks altogether and turn streets at the heart of the city into unique spaces where vehicles and pedestrians can both thrive while giving priority to the latter. Other more futuristic projects are even considering moving sidewalks for pedestrians and to help reduce city traffic. All these initiatives are bringing the individual back to the heart of the city, with vehicles in second place.

There are no comments yet