Predicting the future is not easy, but when they let their imaginations fly, artists portrayed a vision that was occasionally ahead of their time.

By its very nature, the term retrofuturism needed us to wait until the 1980s to have enough material to be able to define it. Lloyd John Dunn, an experimental artist, coined it jokingly to define a contradictory form of art between nostalgia (retro) and what is to come (futurism). For a while, he even published a magazine of the same title, Retrofuturism, which covered all sorts of related artistic and technological trends.

Did the retrofuturism use magazines as windows to the future?

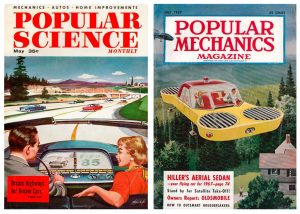

Popular Science Magazine / Popular Mechanics Magazine

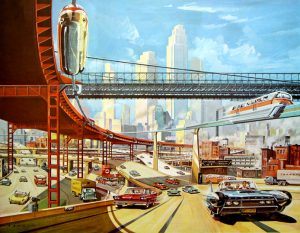

The hallmark of retrofuturism is this idyllic, pristine vision of the future in which artists of all stripes imagined how space exploration, robotics, or modes of transportation would be in a few decades. The roads and highways were no exception, and in fact, iconic magazines from the ‘50s and ‘60s, like Popular Mechanics, Popular Science and Modern Mechanix, dedicated articles, specials, and covers to depicting so-called “dream highways” where flying cars and other inventions traveled from one place to another.

These magazines and what they suggested shared certain characteristics: they generally based their articles on news about scientific advancements and real technology, but they always went one step further and commissioned illustrators and engineers to make drawings and conceptual designs that were often based on rather vague descriptions. If someone said that they were working on a prototype for a flying car with four vertical turbines, the rest did not really matter: off went the artist to illustrate it with a traditional family inside, landing in their home garden on a perfectly manicured lawn. The artistic details were more important than the technical specifications, and in fact, some turned out to be quite shocking – when they did not defy the laws of physics.

Who are the most iconic artists of retrofuturism?

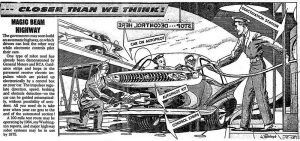

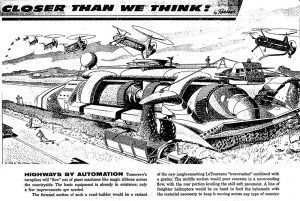

In this movement, there were many iconic artists, including Arthur Radenbaugh, an industrial illustrator and designer who worked for the automotive industry, among other things. His illustrations showed new designs for automobiles running the roads at high speeds on fantastic highways: superfast cars, self-driving cars, flying cars… On this subject, the documentary Closer Than We Think (2017, Brett Ryan Bonowicz) is very interesting in that it shows many of his designs, work techniques, and expert opinion.

Author: Arthur Radebaugh

Author: Arthur Radebaugh

One of his most famous projects was a Sunday comic strip called Closer Than We Think, which illustrated a futurist idea based on news that was coming out. Among them we can find a “Magic Beam Highway,” an idea proposed by General Motors and RCA for including guides in the pavement that helped send electrical pulses to signal vehicles traveling on them. This way, the steering wheel, brakes, and accelerator could be controlled, making them self-driving. In another of his works, there is a “Highway-Building Machine,” which is basically a mechanism similar to the giant tunneling machines used to excavate underground: the machine could pave the roadway as it advanced – like current pavers – and also drill, if necessary. The most futuristic part: a fleet of helicopters would transport raw materials to a tank in the upper part so that the mammoth machine could work without pause. We still have not gotten there… yet.

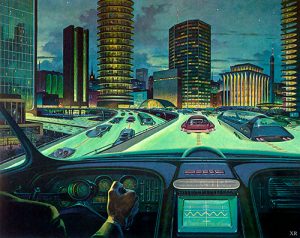

Source: Klaus Buergle

Another of these iconic artists was Klaus Bürgle, whose impressive tome The New Universe (1959) depicted futuristic infrastructures in the form of cities, railroads, highways, and underground tunnels. Many of the recurring ideas: monorails, guided cars, and elevated walkways everywhere.

What does Disney have to do with the retrofuturistic highways?

But perhaps one of the most spectacular examples of retrofuturism is the animated documentary Magic Highway, U.S.A. (Ward Kimball, 1958). Originally commissioned by Disney, it attempts to explain the importance of highways to the development of society, and to do that they showed all sorts of advancements that “will be seen in the highways of a near future.” They were right about some, but others… not so much.

Among other things, it discussed the fact that, due to the high speeds at which the cars of the future would travel, larger, more visible traffic signs (something akin to current LED screens) would be needed, and they would include traffic information and informational bulletins – something that already exists, in addition to what we find on billboards and smartphones, or the screen in the car itself. In the documentary’s prediction, highways would be lit up by “smart lights,” something that is already being experimented with in Norway: streetlights that only turn on when cars are traveling along their paths.

The movie talks about highway surfaces including a heating system for winter to melt ice, something that has also already become a reality. And not even Disney or Kimball would have dreamed about materials such as self-repairing asphalt that, thanks to its steel wool fibers, can prolong its life by being heated by induction (without contact).

Naturally, on this “magic highway” of the future, cars would be equipped with radar in their windshields (which is not so different from LIDAR, which many self-driving cars and drones have), and rearview mirrors would be a “television screen” (many already have these backup cameras). When they say that “you just have to tell the car where you want to go, and presto! time to relax with family,” it seems like they are talking about current standards’ Level 5 self-driving cars, when even the steering wheel is unnecessary. The cell phones that we carry in our pockets are, of course, capable of navigating to anywhere, and they are also ever more intelligent.

It also talks about large trucks with trailers that are remotely controlled from a central base – some models hitch together like trains – which is something that is still currently talked about, and which many believe will be the first truly practical thing that we see: safe self-driving trucks like the Tesla Semi, capable of transporting 40 tons for 800 km without refueling. In fact, the impressive road truck trains that are on the road in Australia are the exact same thing, but with a driver.

How they thought the infrastructure of the future would be?

In the Disney documentary, they also discuss “bridge printers” that would be similar to what we know today as 3D printers that can use plastic as well as metal, concrete, and other materials (this footbridge in Amsterdam is being built with this technique). It is a step beyond bridges with prefabricated pieces, which are also mentioned, and it is already commonplace under the concepts of prefabrication and modular construction.

But we must also recognize that the documentary was not able to predict when or how some of these technologies and infrastructure would arrive, or it was simply wrong in its predictions. For example, it depicted giant overhanging viaducts on canyon walls, something that is impractical – and even less so for a highway – except for pedestrian walkways. It also dreamed up business highways … leading to spaceports where rockets took off to other worlds.

Perhaps the craziest, least practical ideas are also the most fun: from an atomic reactor to dig tunnels (it was the era when anything “atomic” sounded great), fleets of flying robots to tow broken-down cars (repairing them on the highway is not good enough?), or highways to impossible places: from the transcontinental highway under the oceans – something that poses incredible technical difficulties, to the bizarre air-conditioned highway, which would allow cars to travel in a sort of “refrigerated glass tube.” Perhaps air conditioning in the car is not good enough?

In any case, all of these inventions and scenarios made an entire generation dream, and who knows? Perhaps they inspired many of the advancements that we enjoy today.

There are no comments yet