The loudspeaker system announces that the magnetic levitation train has reached the station, and passengers get ready to leave the carriage. We have reached our city after work, and now we’ll take the bus to get home. On leaving the bus, we walk a few metres and then go through the front door. Into the lift, and down to our floor, many metres below ground.

Can you imagine living on floor -100, or B100 (basement) of an underground building? This may perhaps not be everyone’s dream, given that our culture values open spaces and views, but technology could well solve these small details by building large earthscrapers, a type of “tall” building which would dig into the ground in much the same way as skyscrapers rise out of it.

We’re running out of “upwards” space

Large cities are saturated with people, due to a second large wave of migrations from smaller towns. This means that pressure on the environment is increasing, with the space to be shared becoming ever smaller. So much so, that the largest growth in the last 20 years hasn’t happened in urban city centres, but rather in the suburbs.

The map below shows the fluctuations in population over the period 1996-2015 in Spain A large part of the country has once again been losing population, as was the case earlier with the rural migrations of the second half of the 20th century. The difference now is that people are moving from smaller to larger cities.

It is striking how some large population centres, such as Madrid, can no longer accommodate more growth, with the population having grown by “only” 9.59% in 20 years. Around them, however, there is a green belt with average growth of 100% to 500% within the Madrid Community, and a peak of 1414% in Yebes (Guadalajara). In other words: we don’t have enough space. The most densely populated cities are the places where there are highest employment opportunities, something which has been the case in all the great empires of the past. And no one wants to miss out on such opportunities.

So, what do we do when we can no longer build upwards? We are currently building out to the sides, extending large cities over more land, but this is a threat to the environment. It is possible, though by no means certain, that there may be a limit to how large urban areas can be, and that, at a certain point, we will take up the option of building earthscrapers rather than skyscrapers.

We still have, relatively speaking, large spaces on which to build. For example, a large part of homes in cities are less than two storeys high, particularly in the suburbs. However, even if we built more storeys, we will soon run out of space, and cities such as those in Blade Runner didn’t look particularly healthy.

Should we learn to live underground?

Today, building a garage on the first underground level is more expensive than building a second storey up. But considering the soaring price per square metre in many cities, it doesn’t seem too far-fetched that basement floors will start being in demand, considering that ground floors are now more sought-after than ever. Greatly simplifying the problem of access to a home, in a city with ten buildings, each having ten floors, and where the price per square metre is 1,000 Euros (to take a round figure); adding an extra floor to each building in the form of a basement would increase the number of floors from 100 to 110, with the average price per floor dropping to around 910 Euros/m2.

A second basement floor would bring the price down further to 830 euros/m2 through offer and demand. More living space increases the offer, which in turn reduces the price. In other words, living underground could be cheap, especially if we take into account that ground floors are more affordable than first floors, and first floors more than second floors. But we still don’t want to live underground. After all, there is no sun… and we need light, air, views… don’t we? In fact, the past seems to show us that we don’t.

What are the earthscrapers?

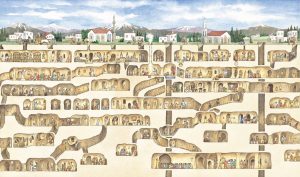

Earthscrapers, or the concept of earthscrapers, is quite old. In fact, humans lived in deep caves, hundreds of metres high, well before building the first huts. And even before that they had already started to dig up the ground. In his book Civilizaciones bajo tierra (2017) (Underground Civilisations), Juan José Revenga talks of the underground city of Derinkuyu (Cappadocia), which had some 20 underground levels. Obviously, modern buildings were not yet there.

Source: Wikipedia

Having said this, the first vertical constructions did away almost completely with the idea of caves, for several reasons. One of these is that it is not an idea that can be used the world over, since there are certain places where it is impossible to builds downwards. Another reason is that technology had not yet reached the point at which it could make living underground comfortable.

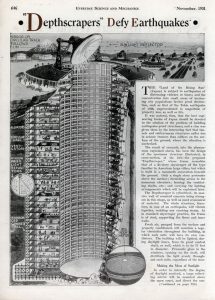

Moreover, bricks made vertical structures become cheaper, and so caves were left only to serve as basements, larders, cellars, etc. Interest in underground architecture emerged again towards the beginning of the last century. This page from Everyday Science and Mechanics, from November 1931 (see photo below), shows a cylindrical earthscraper designed to withstand earthquakes, something which nature does very well but which our conventional buildings have still to learn about. Contrary to what it may seem, earthscrapers would be able to withstand movements in the Earth’s crust relatively well.

Source: Modern Mechanix

The reason why nobody has built a similar construction to date is that there has been no need for one yet. However, the article A review of underground building towards thermal energy efficiency and sustainable development, published in 2015, talks of how earthscrapers could help build cleaner cities taking into account only the impact of climate control, which accounts for close to 40% of greenhouse gas emissions. The other major sources of GHG are transport and the meat industry. It would appear that living underground has its advantages.

What are the Advantages and disadvantages of living underground?

Living underground has certain advantages, not only as protection from animals or other enemies, or for avoiding earthquakes. As regards temperature, it is much more stable: at a depth of one metre underground, daily temperature fluctuations are around ± 5ºC, but at 5 metres deep this is less than ± 1ºC. Moreover, inside caves or dugout areas, the temperature tends to be around 17ºC to 23ºC, very near our point of thermal comfort, as opposed to over ground, where temperature varies greatly due to the Earth’s rotation and the effect of sunlight.

There are also advantages in terms of humidity, since relative humidity inside a cave is around 50%, something which is much healthier than our air conditioning today, which tends to make our air dry, or the pollution in our cities, which is not exactly healthy for our lungs.

Source: Unsplash | Author: Daniel Burka

Some time back we saw how architecture can learn how to vent heat from buildings by copying termites. Today we will see how our ancestors heated underground cities. With a wood furnace at the bottom of the structure, a series of (hand-dug) channels crossed the whole city, always in an upwards direction, in a similar way as kitchen chimneys.

Hot air rose, heating the various homes. If building underground, other heating systems could be used, such as resistive heating or, since we are already underground, geothermal systems using the heat from the subsoil; or aerothermy, using energy from the air. Or a combination of all these. Building hydraulic circuits for geothermal energy is simple and something we already do today; and aerothermy is becoming increasingly developed, with an energy efficiency level of between 300% and 500%. But it’s not all advantages.

When we live for many years in places which are literally short on views, such as narrow prisons or homes without views in which we spend a large part of our time, we have problems conserving our long sight because our eyes get used to looking only at objects which are close by. It’s a bit like blindness through adaptation to the environment, which can happen over many decades. If we do build earthscrapers, we should make them big, as we will see in some examples later on.

Although it may sound strange, the radiation emitted by the Earth’s crust can also be harmful for our bodies. Granite, for example, is a low-emitting radioactive substance if we live on it, especially where there are small amounts in the ground. It has significant traces of natural uranium, which is radioactive, and micro bubbles of radon, also radioactive, which disintegrates (in our lungs) to give solid polonium. If we were to build earthscrapers, we would have to be extremely careful when building a reinforced perimeter or choosing the right location.

Some proposals for earthscrapers (not built)

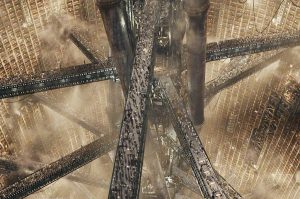

Source: Wikia

Many readers will recognise in the above photo the fictional city of Sion (Matrix, 1999), inhabited by some 250,000 people. It is in fact a giant earthscraper dug into the Earth’s crust. However, it is not a real design, and our technology is as yet very far from being able to build such a wonder. Moreover, machines have not yet rebelled and robots still help us considerably.

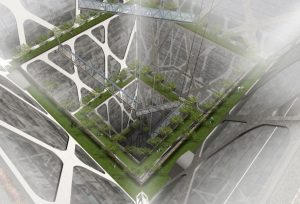

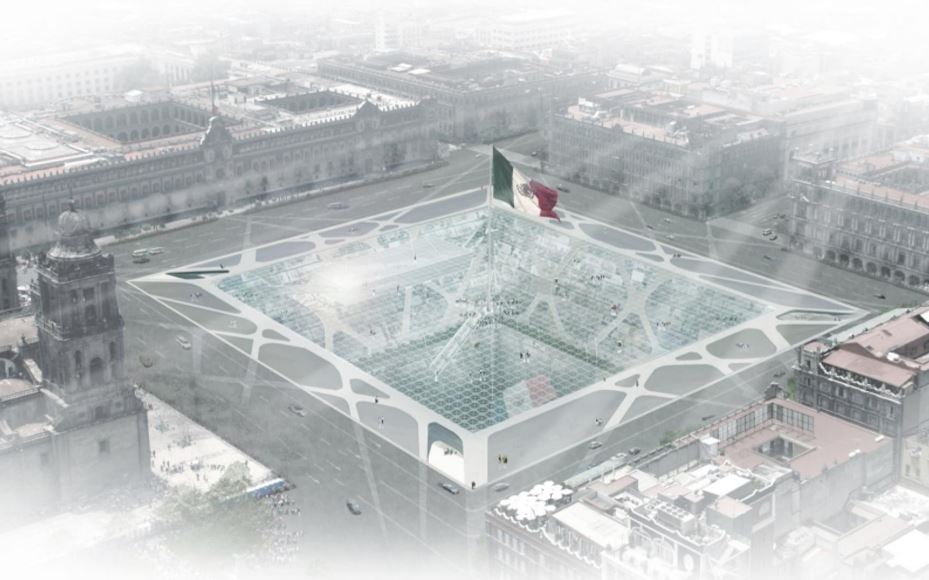

There is no need for us to flee underground. If we want real examples of modern engineering we have to go to Mexico, where the BNKR Arquitectura studio designed The Earthscraper in 2009, as part of a competition held in the capital city. Here we’re showing you two photographs, although the full project is available in the preceding link.

- Mexico’s Constitution square / Source: unquerarquitectura

- Mexico’s Constitution square / Source: unquerarquitectura

- Mexico’s Constitution square / Source: unquerarquitectura

The first photograph shows what Mexico’s Constitution square, called El Zócalo, would look like once the earthscraper was built. The square would still be accessible to pedestrians. Concerts held in Mexico City would not doubt reduce the number of lumens reaching the inside of the structure, since it takes its light from the sun. The design idea is to install reflecting mirrors around the earthscrapers so that just a small amount of natural light would be enough to light the homes.

Source: Bunquerarquitectura

The second photograph (above) shows what a pedestrian walking in the square above The Earthscraper (if bold enough to do this!) would see. Much like an inverted ziggurat, this miniature city would have everything required for daily life: supermarkets, shops, parks, schools, etc., with the advantage of people simply taking the lift and travelling 65 floors up to reach Mexico City. Incredible!

An earthscraper on Mars with artificial light?

Source: Coelux

See the skylight in the photo above? It’s a trick: it’s not a skylight, but a lamp in the shape of a horizontal window, made by company Coelux. And the blue you can see is not sky, but a clever simulation so that all who pass below it “feel” the warmth of the sun. Except that there is no sun, though the thermal sensation is the same. Lights of this type, which we can install in the -5 storey of a car park to make us feel that we are only a couple of metres from the outside world, would be the solution in underground settings.

We have mentioned on a couple of occasions that we do not like the feeling of being trapped between walls, and this type of simulation can be of great help, especially if we look to build beyond the Earth. If we think back on the first Resident Evil (2002) film, workers in The Beehive, an underground complex, had false windows looking out onto open views.

Now that Elon Musk has launched an electric convertible into space beyond the orbit of the red planet, it would not be right to finish this article without talking of the impact that earthscrapers could have on the colonisation of space. Mars is a good example, having an atmosphere made up mainly of carbon dioxide (95%), nitrogen (3%) and argon (1.6%). This, together with the large amounts of solar radiation impacting the planet, would leave us no option but to live in caves. As in the past, but in another world. Venus is not much better, considering that air pressure is 90 atmospheres (what a hydraulic press uses to squash a car), the temperature is over 426ºC (we would melt), and the air made up of sulphur. If we were ever able to land there, we would have to quickly seek refuge underground.

The moons of Jupiter aren’t much of an improvement either. Although Europa and Io might seem like good places on which to build space stations, Jupiter’s background radiation would make it a bit complicated to live there. Again, earthscrapers would be the solution to any migratory problems, if we had them. For the time being, earthscrapers are no more than an imaginary project, to be drawn on paper or designed in sophisticated digital programmes.

It is much more likely that your whole neighbourhood is built at height than that we will ever get to live underground. But human needs and technology have managed to get other once imaginary concepts, such as aeroplanes, off the ground, so we can never rule anything out.

There are no comments yet